The Hidden Hero Fueling Soft-Landing Hopes: A Boost in Supply

Rising labor force, productivity lowered inflation despite still-strong growth, taking pressure off Fed to raise rates

By Nick Timiraos

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell signaled an important shift this month when he said the central bank didn’t necessarily have to worry about stronger growth feeding through to higher prices.

The reason: The U.S. economy’s speed limit, known as potential growth, appears to have temporarily moved up thanks to easing bottlenecks and a boost in the number of people available to work and, possibly, in productivity, or the output that each worker produces.

It underscores why Powell played down fears that a surge in growth to a 4.9% annualized rate in the summer would lead to accelerating price pressures.

While growth has likely stepped down in the current quarter, it is still reasonably healthy.

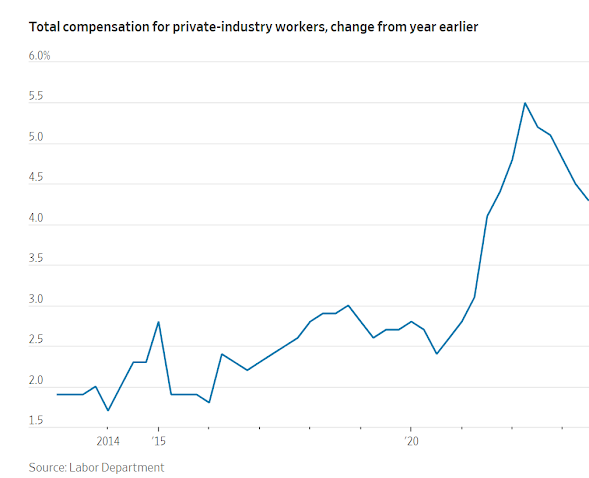

Inflation and wage growth have continued to slow.

In the workhorse models most economists use, including the Fed’s, when growth consistently exceeds its long-run trend of around 2%, unemployment falls and inflation pressures increase.

Below 2%, the opposite happens.

Until this month, Powell has consistently said that a period of “below-trend growth” would be needed to bring inflation down.

And yet growth has exceeded 2% this year, the unemployment rate has risen and underlying inflation fell to an annualized 2.8% in the six months through September, down from 4.5% in the previous six-month period.

At a Nov. 1 news conference, Powell recast his rhetoric, saying that the economy now needed to grow “below potential.”

Powell was making a subtle but significant distinction between the economy’s long-run trend growth rate and short-run potential growth.

Potential might be higher or lower than the long-run trend depending on the supply of labor and productivity.

Powell’s view is still that over the long run, the U.S. economy should grow 2%.

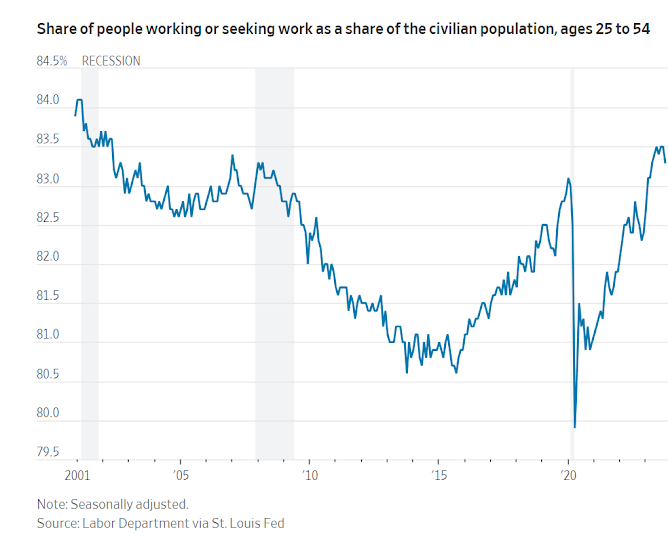

But an uptick in both immigration and workforce participation rates, together with easing supply bottlenecks, has raised the short-term speed limit for growth, he said.

Catch-up growth from pent-up supply

Potential growth is temporarily “elevated for a year or two right now over its trend level,” said Powell.

“And that means you could be growing at 2% this year and still be growing below the increase in the potential output of the economy.”

Powell was providing a narrative to explain Fed officials’ longstanding expectation that inflation could come down without the huge rise in unemployment of the last serious inflation fight in the early 1980s.

In effect, the pandemic might have caused a one-time decline in the economy’s capacity to supply goods and services, and supply is now catching up.

A shortage of semiconductor chips made it harder for automakers to ramp up production amid a huge increase in demand in 2021.

Americans were flush with cash, and interest rates were at rock bottom for as far as the eye could see.

Car prices skyrocketed.

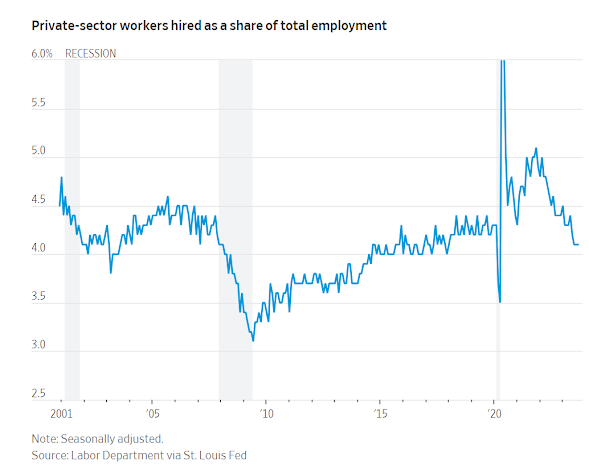

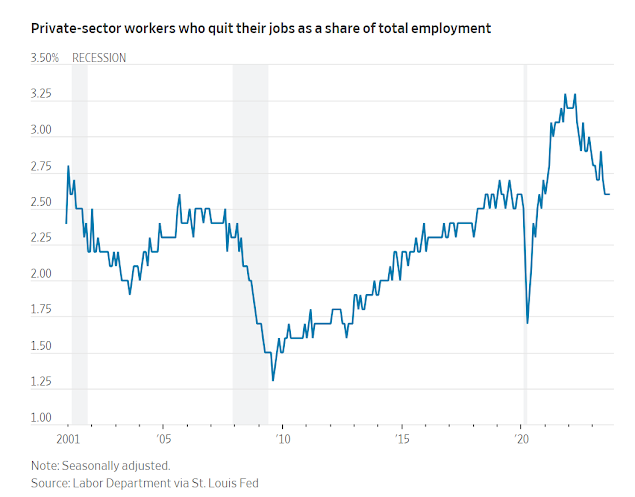

And a similar dynamic unfolded in labor markets.

Immigration slowed to a crawl and many workers left the labor force, leading to shortages.

Wages shot up.

The transitory story

In April 2021, Fed leaders at first said inflation would be “transitory” because they thought supply bottlenecks and worker shortages would sort themselves out in mere months.

By that fall, price pressures were worsening and demand appeared to have been overstimulated.

The Fed pivoted by accelerating plans to withdraw stimulus.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine added fuel to the inflationary inferno by sending up the prices of raw materials in early 2022, when the Fed first raised rates.

Inflation hit 9.1% three months later.

The Fed turbocharged rate hikes, lifting them at the most rapid pace in four decades.

Their economic projections had long called for a painless decline in inflation, the so-called soft landing.

But their conviction ebbed as inflation stayed high.

By year’s end, Powell and others conceded recently, they began to lose hope that the supply of workers would recover.

Otherwise, prices would keep rising, particularly for labor-intensive services.

This year, the supply rebound finally showed up.

Bottlenecks eased, rising immigration and workforce participation boosted the labor force, and a pandemic-era boom in newly built apartments hit the market.

Those are tamping down goods prices, rents and wages.

Having more workers enter the labor force is a relief valve that is allowing “wage growth to slow without having a big correction in demand,” said San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly.

The pandemic saw an increase in construction of residential buildings. PHOTO: JOE RAEDLE/GETTY IMAGES

Prospects for bringing inflation down without a serious downturn have brightened because “other parts of the economy, which we don’t control, have been adjusting,” she said.

For those economists who had long cautioned against the orthodox assumption that a large increase in unemployment was needed to bring inflation down, this is “a huge relief.

We’ve all been humbled,” said Julia Coronado, founder of economic-advisory firm MacroPolicy Perspectives.

The Fed appeared to “give up on labor supply just as we were about to get a pretty epic recovery in labor supply.”

This doesn’t mean the Fed was wrong to raise interest rates.

Those higher rates played an important role in restraining demand while the supply-side of the economy healed itself, said David Mericle, chief U.S. economist at Goldman Sachs.

“Supply was always going to catch up,” he said. “But making sure supply and demand came back into better balance on a timely basis has been important.”

Will supply and productivity gains last?

Supply could also be benefiting from productivity growth, which jumped in the second and third quarters.

The question is whether this higher potential persists.

If it does, it would increase the central bank’s confidence that inflation returns to its 2% target, and perhaps bring forward when it can start to lower interest rates from 22-year highs of around 5.3%.

Coronado is optimistic that supply improvements will be sustained because of an increase in business investment and a hot labor market that improved the efficiency of matching employees with new jobs.

“It makes your trade-offs a lot more favorable.

You don’t need to keep hammering the economy until it goes into a recession,” she said.

But Powell earlier this month warned the recent rise in potential might have run its course.

For example, immigration might slow or fall in the future, and higher child-care costs could lead some working mothers to step out of the workforce.

Without an assist from supply, the Fed would return to its default assumption that slower growth is necessary for inflation to fall further, putting off rate cuts.

Tom Fairless contributed to this article.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario