Qatar’s Grandiose National Vision 2030

Its goals are bigger than its accomplishments.

By: Hilal Khashan

In 2008, Qatar unveiled an initiative to make the country an advanced society by 2030.

Qatar National Vision 2030 laid out a comprehensive sustainable economic development plan for the present and future generations, where they can thrive in a just and safe environment.

The initiative promised to ensure the personal freedoms of the country’s citizens, involve them in formulating its public policy, acknowledge the role of women in society and empower people to serve their country better.

But the plan isn’t as progressive as it seems at first glance.

It stresses that modernization efforts must preserve Qatar’s traditions and safeguard its society’s moral and religious values.

It does not challenge the prevalence of archaic social values, guarantees Qataris a high standard of living and keeps women under the grip of male domination.

Development is about breaking with traditional values that do not promote hard work and encourage dependence on state welfare.

While the country can boast of some notable achievements in its international standing, the government has made little progress toward genuine modernization in order to avoid upsetting its tribal society’s traditional foundations.

Unfriendly Neighbors

Qatar’s ambitious modernization agenda was in part a reaction to the hostility it has experienced from its Gulf neighbors.

In 1968, Britain withdrew its forces from East of Suez and, in 1971, ended Qatar’s protectorate status.

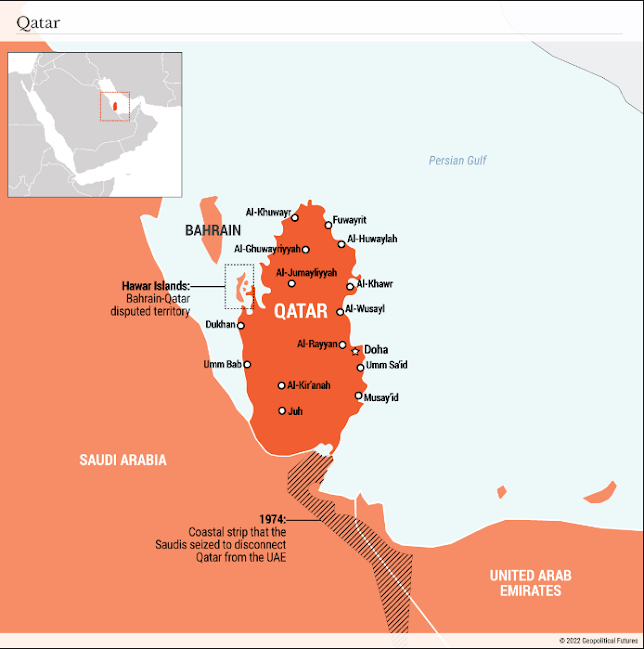

Independence put Qatar face to face with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (mostly the emirate of Abu Dhabi) and Bahrain, adversaries with whom it fought military battles in the 19th century.

The territorial dispute between Qatar and Bahrain dating back to 1936 flared up again in the 1980s.

After arbitration in the International Court of Justice in 2001, the disagreement reemerged in 2017 when Bahrain joined three other Arab countries in imposing a blockade against Qatar.

However, Qatar’s most contentious relationship in the region is with Saudi Arabia, which opposes Qatar’s independent foreign policy and whose dominance of the Gulf Cooperation Council Qatar has rejected since it joined the group, reluctantly, in 1981.

The two countries also have a border dispute that a 1965 agreement failed to resolve, leading to clashes in 1992 in the border area of Khafus, which the Saudis had seized.

They fully demarcated their shared border only in 2001.

Saudi Arabia has repeatedly tried to isolate Qatar from its neighbors.

After the Saudis and the UAE signed the 1974 Jeddah Agreement, which was meant to settle their own border dispute, Riyadh seized a 45-kilometer (28-mile) coastal strip that connected Qatar to Abu Dhabi to prevent any attempt at unification.

In 2004, Riyadh also vetoed the construction of a causeway linking Qatar and the UAE.

But Saudi efforts to turn Qatar into a satellite state have had the opposite effect: They drove the Qataris to want to become an independent country and a global partner in defense, innovation and economic governance.

National Vision 2030

Over the past few decades, Qatar has made several development achievements.

In 1996, it launched the Al-Jazeera media network and built the Al-Udeid Air Base, which also hosts U.S. Air Force personnel.

A year later, it inaugurated Education City.

It also built an impressive sports complex in 2003 and was named host of the 2022 World Cup by FIFA in 2010.

Doha also emerged as a trusted mediator of regional and international conflicts over this period.

Encouraged by its achievements, Qatar introduced a blueprint, dubbed National Vision 2030, for realizing its development goals.

The ultimate objective of the plan is to create a diverse and versatile economy driven by an energetic private sector.

Its success depends on providing Qatari youth with an education adhering to the highest international standards in order to develop their ingenuity, creativity and critical thinking.

National Vision 2030 focuses on creating a competent Qatari labor force composed of workers with a strong work ethic and occupying senior management positions in business, health and education.

It carefully addresses the integration of women into economic life and commits to opening new employment opportunities for them.

Although Qatar is predominantly a country of expatriates, National Vision 2030 isn’t meant for them.

Official figures on demographics in Qatar are unavailable, but the United Nations estimates that the country has 2.75 million residents, 12 percent of whom are natives.

Two-thirds of Qatar’s population are Asians, while Arabic-speaking expatriate communities account for slightly over 15 percent of the total population.

The country’s population is increasing due to the influx of expatriate workers needed for infrastructure projects and economic expansion.

In 2000, its population reached just 615,000 residents, which increased to 1.44 million in 2008, the year National Vision 2030 was announced.

Despite the plan’s call to focus foreign worker recruitment on skilled labor and high-quality personnel, Qatar’s population has nearly doubled since 2008, driven largely by recruitment of unskilled laborers from abroad.

Tribal Politics

Qatar has dozens of tribes with transnational family ties in Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and Bahrain.

The Tamim tribe, which has dominated Qatari politics since the mid-19th century and includes the ruling al-Thani dynasty, relocated from Saudi Arabia’s Nadj region.

Meanwhile, the al-Murrah and al-Hawajir tribes constitute two-thirds of Qatar’s indigenous population.

In 1995, Sheikh Hamad al-Thani staged a coup to oust his father, Sheikh Khalifa, from office and succeed him.

A year later, a failed military coup backed by the al-Murrah tribe led to a government purge against the tribe and the arbitrary revocation of citizenship of at least 6,000 of its members.

Even more al-Murrah tribespeople lost their citizenship after Saudi Arabia imposed a four-country blockade on Qatar in 2017.

Transnational tribes’ rejection of the state, which they see as a nebulous entity, often casts doubt on where their loyalties lie, which explains why the Qatari government was able to revoke the al-Murrahs’ citizenship so easily.

But modern countries imprison wrongdoers; they do not make them stateless.

To protect its tribal traditions, Qatar has a strict naturalization policy that grants citizenship to no more than 50 people each year.

The law classifies naturalized people as non-native Qataris.

They are ineligible to hold key government positions and have no right to vote, run for public office or serve on legislative bodies.

Native or original Qataris are individuals who can prove that they maintained continuous residence in the country from 1930 until the issuance of the 1961 Nationality Act – as well as the children of people who qualify as native Qataris.

The nationality law grants citizenship to the children of a naturalized man but does not recognize them as native Qataris, effectively excluding them from society.

This essentially violates the constitution, which gives all Qatari citizens the same rights and privileges.

In 2021, Qataris went to the polls for the first time to elect 30 members of the 45-seat Shura Consultative Council.

(The other 15 members were appointed by the emir of Qatar.)

The council in theory oversees the functions of the executive, though at least two-thirds of its members must agree on any course of action, meaning at least some of the emir’s own appointees must endorse any decision.

The government didn’t promote the election as a move toward democracy.

Instead, it presented it as “a step towards a closer relationship between citizens and state.”

The vote reflected the country’s tribal segmentation as each of the powerful tribes elected its own representatives to the council.

The emir felt the need to rally the people behind the government in its feud with Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt.

It was only after the 2017 blockade that the government decided to go ahead with preparations for the election, which was initially proposed in the 2004 constitution.

Emir Tamim bin Hamad’s behavior mirrored that of Saudi King Fahd, who promised to establish a consultative council after succeeding to the throne in 1982.

He pledged to approve it in November 1990 after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait and the arrival of U.S. troops to Saudi Arabia, a move that many religious Saudis objected to.

Saudi Arabia’s Consultative Council had no legislative prerogatives and failed to prevent Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman from concentrating power in his hands.

Qatar’s Shura Council is also unlikely to pave the way toward a democratic transition for the country.

Discrimination Against Women

National Vision 2030 also promotes women’s full participation in all manners of public life, including employment.

The reality, however, is strikingly different.

The number of working women in Qatar is less than half the number of working men, even though there are at least twice as many female college graduates as male.

All 29 female candidates who ran for election last year failed to win a seat, prompting the emir to appoint four women to the council.

Qatari law discriminates against women, forcing them to have a male guardian without whose consent they cannot travel or marry.

A married woman must be accompanied by her husband to a gynecologic clinic, and a single woman must be escorted by a legal guardian.

Hospital admission requires a married woman to present a copy of her husband’s passport or a single woman to present her guardian’s ID.

Qatari society is suspicious of women, whether they are natives, expatriates or travelers.

In October 2020, Qatar forced women on several flights to Australia to endure a humiliating pelvic examination after finding an abandoned newborn at Doha’s Hamad International Airport.

Qatar made tremendous progress over the past quarter century from an obscure desert emirate into a world-renowned media center, educational and sports hub, and conflict mediator.

It established an independent foreign policy and blunted its GCC neighbors from undermining its sovereignty.

But its achievements had little impact on the native population’s economic productivity, thanks to the country’s hydrocarbon riches, which attracted expatriates to run the country’s economy and operate its infrastructure.

National Vision 2030 sought to build a modern society, integrate Qataris into the economic cycle and equip them with the tools of modernity.

Fourteen years since its launch, Qatar still doesn’t seem any closer to being on the path toward modernization, and it’s unlikely that things will change in the remaining eight years.

Political considerations, rather than a desire for real modernization, drive the government’s development ambitions as the scope of the projects it has undertaken far exceeds what Qatar’s small population needs.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario