American firms are in worse shape than reported earnings indicate

By Justin Lahart

An earnings metric that measures profits at U.S. companies down to the local diner, not just firms listed on the S&P 500, is painting a worrying picture. Photo: Eve Edelheit/Zuma Press

U.S. companies might be feeling a lot more pinched than they appear. That could have serious repercussions for both the stock market and the economy.

Earnings season is about to get under way, and it looks as if the news won’t be good. Analysts polled by FactSet estimate that earnings per share for companies in the S&P 500 fell by 4.1% in the third quarter from a year earlier. Even with the allowance that actual results probably won’t be quite as bad, since the bulk of companies usually top estimates, it looks as if it will mark the third quarter in a row that earnings slumped.

It is a comedown from last year when, buoyed by a strengthening economy and corporate tax cuts, earnings grew by 20%. Trade tensions and slower economic growth are weighing on sales, while rising labor costs are cutting into bottom lines. The net profit margin for the S&P 500—income as a share of sales—fell to an estimated 11.3% in the third quarter from 12% a year earlier, according to FactSet.

Margin pressures are more than just a problem for shareholders. Because they drive companies to cut costs, they can cause trouble for the economy. The hope is that since S&P 500 profit margins are still historically high, the cost-cutting impulse will be subdued.

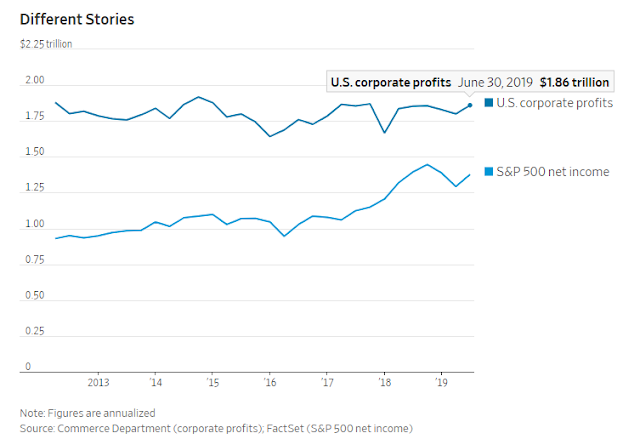

But figures from the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis offer a very different view of what has happened with overall U.S. corporate profits over the past several years. Growth has been lower and margin pressures worse than the S&P 500 figures.

According to the BEA measure, after-tax profits in the second quarter were only 6% higher than they were three years earlier, which compares with a gain of 50% in S&P 500 net income over the same period. After-tax profits as a share of gross domestic product—a rough approximation of overall U.S. profit margins—slipped to 8.7% from 9.4% over that period, despite the profit boost from the 2017 tax cut.

There are important differences between the BEA profits measure and S&P 500 earnings numbers. First, the BEA is measuring profits at all U.S. companies, down to the local dry cleaner, while the S&P 500 figures are only for the large, public companies that make up the index. Many S&P 500 companies are multinationals with substantial overseas earnings that aren’t included in the BEA’s figures.

Additionally, the S&P figures are based on companies’ financial reports. The BEA, while using financial reports for its initial estimates, ultimately relies on tax data.

Still, there is substantial overlap between the two measures, and they usually track each other.

When they don’t, as in the late 1990s, when S&P 500 profits surged but BEA showed profits stagnating, it can be a sign that something is amiss. Ultimately, investors found that their confidence in big companies’ earnings power in the late 1990s was misplaced. Stocks fell sharply.

The most important difference between how profits are reflected in companies’ financial reports and how they are counted by the BEA might be in the treatment of capital gains, says economic consultant Joseph Carson. Indeed, the BEA itself has stated that the reason its measure didn’t show that late 1990s run-up in profits “was primarily attributable to capital gains.”

Under accounting rules, capital gains and losses can make their way into earnings in a variety of ways, notes David Zion, head of accounting and tax research firm Zion Research Group. If a company’s equity investments rise in value, for example, that unrealized gain can flow into the income statement. As a result of new accounting rules adopted last year, capital gains are now even more apt to show up in earnings.

The BEA, on the other hand, aims to measure profits companies generate through their business operations, and so excludes capital gains and losses.

The implication is that a fair amount of the earnings growth the S&P 500 has exhibited in recent years might be ephemeral, related to gains in the value of companies’ investments rather than the underlying strength of their operations.

Under the hood, then, profit margins aren’t as good as they appear. If business starts to falter, companies’ may take an ax to costs, with bad repercussions for the economy.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario