Remember The Trade Wars? This Isn't Complicated

by: The Heisenberg

- Despite the fact that this week saw the official implementation of "phase 2" of the U.S.-China trade dispute, trade wars took a back seat to domestic political theatre.

- Rest assured, trade wars won't remain relegated to the news cycle back burner for long.

- What I wanted to do on Saturday is bring you a straightforward assessment of tariffs' likely impact on S&P 500 earnings and on the U.S. consumer.

- There isn't anything complicated about this.

- Rest assured, trade wars won't remain relegated to the news cycle back burner for long.

- What I wanted to do on Saturday is bring you a straightforward assessment of tariffs' likely impact on S&P 500 earnings and on the U.S. consumer.

- There isn't anything complicated about this.

The title here is of course a reference to the fact that trade war news took a back seat to domestic politics in the U.S. this week.

It's a quip, and not a particularly creative one, but it resonated on Friday, and it speaks to the manic nature of the news cycle that has, at various times over the past two years, overwhelmed market participants' collective ability to process the deluge of potentially relevant incoming information.

And please, save me the "it's all noise" line, because anyone who really trades knows it's only "all noise" until an algo misreads a headline and runs everybody's stops.

"Remember XYZ?" has become something of a common refrain on financial Twitter (or, "FinTwit", for short), and while anyone could have made the quip that serves as the title to this post, I'll attribute it to one of FinTwit's more widely followed pseudonymous accounts:

Well, let me assure you that to the extent folks forgot about trade wars this week, the market's memory will be jogged soon enough. While I'm obviously predisposed to suggesting that most political news has market ramifications, the political soap opera that captured everyone's attention in the U.S. this week only matters for markets to the extent it influences the U.S. midterms. That effect might be large, but it's a second order effect, which means it's inherently untradable in the short run.

On Thursday, as everyone scrambled around at their desks to try and find a live feed they could stream of the Senate Judiciary Committee proceedings, the World Trade Organization was like that kid in the back of the classroom who never gets called on by the teacher ("Me, me, call on me, please!").

Had anyone cared to call on the WTO Thursday, they would have discovered that the organization slashed its 2018 trade growth outlook to 3.9% from 4.4% in April.

Additionally, the WTO said merchandise trade growth will be 3.7% next year, down from a projected 4% in their previous Outlook.

Additionally, the WTO said merchandise trade growth will be 3.7% next year, down from a projected 4% in their previous Outlook.

Here's what WTO Director General Roberto Azevedo said in a statement:

While trade growth remains strong, this downgrade reflects the heightened tensions that we are seeing between major trading partners. More than ever, it is critical for governments to work through their differences and show restraint.

That warning came just three days after the latest round of U.S. tariffs on China went into effect. On Monday, levies on $200 billion in Chinese goods were implemented and it's widely expected that the Trump administration will move ahead with duties on an additional $267 billion in goods before year-end.

Perhaps the most important thing for investors to understand about the trade frictions in the context of U.S. equities (SPY) is that stocks aren't "ignoring" the effects. Rather, the effects simply aren't showing up in the fundamentals yet. More simply: There's nothing to "ignore" or to respond to.

The tax cuts and expansionary fiscal policy have created enormously powerful tailwinds both for U.S. corporate bottom lines (record earnings growth) and for the domestic economy (while the "hard" data is starting to disappoint relative to consensus, it's still robust, and the "soft" data is simply euphoric).

Those same policies are dollar positive (via the read-through for U.S. monetary policy). A stronger dollar puts pressure on ex-U.S. risk assets (think: emerging markets that have borrowed heavily in USD) while the threat of further trade tensions dents the outlook for global growth.

In sum, there are fundamental reasons to be long U.S. stocks and fundamental reasons to be concerned about ex-U.S. assets.

Little wonder then, that U.S. equities have diverged from their international counterparts. It isn't some "mystery". In fact, it's the opposite of a mystery. Sure, the unprecedented divergence argues for a scenario where ex-U.S. assets "catch up" into year-end (that's the "convergence trade"), but if all you're looking at are the fundamentals, well then the current juxtaposition is not only not a mystery or an example of U.S. stocks "ignoring" reality, but rather everything acting exactly like you would expect it to act.

Sure, markets are supposed to be forward-looking, but they're also supposed to be efficient price discovery mechanisms. Those two characterizations of markets' "proper" role sound good in theory and in the textbooks, but in reality, market participants are a myopic bunch and post-crisis monetary policy has stripped capital markets of their ability to act as mechanisms for price Discovery.

I'm going to go ahead and assume that although you and I are, like everyone else, tempted by short-sightedness and the allure of riding the next assumed leg higher ("climbing the wall of worry", as it were), we're also interested in thinking about what the longer-term ramifications of the trade frictions are for the U.S. companies in which we have an ownership stake via equities. Remember, this isn't supposed to be a casino. Don't lose sight of what it means to own stock.

As I put it earlier this week, if the trade tensions keep headed in the direction they're headed, it will affect corporate bottom lines and guidance.

On that score, there isn't anything particularly complicated about the math or, more generally, about the transmission mechanism between tariffs and the stocks you own.

To reiterate, it now seems highly likely that the U.S. will end up taxing the entirety of Chinese imports to the U.S. The Trump administration adopted a 10% initial rate in the latest round of tariffs, but promised to more than double that to 25% starting in 2019 if there's no resolution.

The President and his aides have made it abundantly clear that retaliation from China will be seen as cause for the U.S. to slap levies on the remainder of Chinese imports.

If we assume that the rate in a theoretical "third phase" would be 25% (and that's probably a reasonably safe assumption, although I suppose it would be possible to lift the rate on the list that corresponds to "phase 2" while applying a 10% rate to the prospective new list), then earnings growth for the S&P 500 flatlines in a worst case scenario.

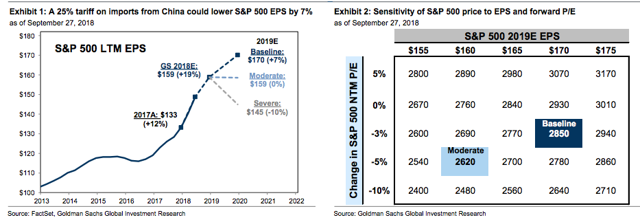

What constitutes a "worst case scenario"? Well, here are the specifications and numbers, via a Goldman note out Friday evening:

Tariffs represent a threat to corporate earnings through higher costs and lower margins. For all US industry, roughly 15% of cost of goods sold is imported. Given S&P 500 constituent firms are more global in nature and have more complex supply chains than overall industry, we estimate imports account for roughly 30% of S&P 500 COGS. This estimate is consistent with the 30% share of S&P 500 sales generated outside the US. Imports from China account for 18% of total US imports. Our baseline earnings forecast is S&P 500 EPS jumps by 19% to $159 in 2018 and climbs by 7% to $170 in 2019. Consensus bottom-up estimates are slightly higher at $162 (+22%) and $178 (+10%), respectively.

For a top-down tariff sensitivity analysis, we conservatively assume no substitution to other suppliers, no pass-through of costs to consumers, no boost to domestic revenues, and no change in economic activity. Given those assumptions, a 25% tariff on all imports from China would lower our 2019 S&P 500 EPS estimate by roughly 7% to $159, flat vs. 2018. If forecast EPS drops to $159 and the forward P/E contracts by 5% to 16.4x, the S&P 500 would fall to roughly 2600 (-10% from current levels).

Please note that there is exactly nothing complicated about that analysis. A first-year college econ major could understand it on the first read. If a third of your COGS is imported, well then, you're going to get significant margin pressure in a protectionist environment. The only way you don't get margin pressure is to upend your supply chain (i.e., source from locales that aren't subject to the tariffs) or raise prices. At the aggregate (i.e., index) level, the only way to mitigate these effects barring a significant rethink of supply chains and/or higher prices, is to sell a bunch more stuff, presumably on the back of a continued upswing in domestic economic activity.

Here's a bit more from Goldman on margins:

Rising input costs force firms to raise prices or sacrifice profitability. In part due to the boost from corporate tax reform, S&P 500 net margins have surged to all time highs (10.7%). However, earnings results and management commentary have underscored the challenge companies are facing to keep up with rising costs and the pressure this could eventually put on profit margins. The most recent National Association of Business Economics Survey showed a large share of respondents reporting rising material (48%) and wage costs (48%), and a much smaller share reporting rising prices charged to customers (20%). In the past, this dynamic has preceded declining S&P 500 EBIT margins.

Again, there is nothing at all complicated about this and that's what makes it perplexing when I see retail investors suggest that somehow the trade wars can continue on the current trajectory without ultimately impacting U.S. stocks.

The only way that kind of thinking is consistent with reality is if either the trade frictions dissipate or else if multiples expand. The former option (i.e., easing trade tensions) is obviously the more desirable outcome, because the latter simply means paying more for every dollar of earnings.

And see, here's the other thing: I continue to worry that the incessant media attention on the U.S. economy is leading directly to a scenario where U.S. consumers are increasingly oblivious to the straightforward costs that will accrue to them from trade frictions. The Bloomberg Consumer Comfort Index, for instance, is sitting at its highest level since 2000.

Contrast that with the following commentary from Barclays, excerpted from the bank's latest sweeping global outlook piece (which, by the way, strikes an overtly optimistic tone, so please don't mistake the following for bearishness):

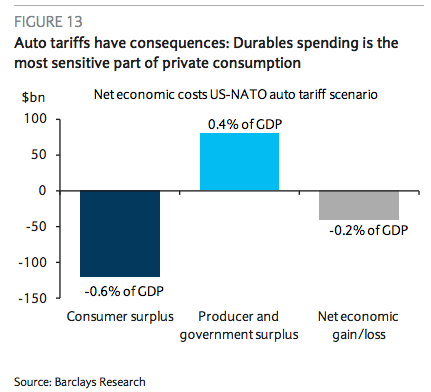

Although losses from a global reduction in trading volumes following a withdrawal of the US from the global trading system would not be trivial, the losses from a bilateral US-China trade dispute or an increase in auto import tariffs may be less than some expect given the heightened rhetoric regarding the subject of trade barriers. One reason it is so heated, despite what appear to be minor economic costs short of a full-blown trade war, is that the net costs obscure concentrated losses. By this we mean that tariffs act as a tax on consumption, with losses borne primarily by consumers, and the net economic costs include offsets from increases in producer and government surpluses. In our baseline US-China scenario, for example, we estimate plausible losses to US consumers at about 0.6% of GDP, only some of which is transferred to the government and corporate sector in the form of tariff revenues and profitability.

The same is true for tariffs on trade in autos; plausible losses to consumers could be several times the net economic loss. On one hand, durables represent the most volatile part of personal spending, and sizeable price increases will impose costs on households. Yet domestic production may expand, and additional revenues to the government, if largely saved, could provide offsets. Altogether, relatively modest estimates of the net economic costs may trade off up-front losses for consumers against medium-term gains from producer and government surplus.

Got that? The cost of this is ultimately going to be borne by consumers. It is not at all realistic to expect corporate management teams to avoid passing on the costs associated with a new global trade regime forever. In order to avoid raising prices, management would have to be willing to renegotiate every aspect of their supply chains that involves imported COGS and eat whatever's left over in terms of cost pressures. Does that sound realistic to you? Of course not. Especially not in an environment where U.S. corporations are perhaps more zeroed in on the interests of their shareholders than ever before.

When you think about that in the context of an economy that depends heavily on consumer spending, you start to wonder whether ebullient consumer sentiment might be sorely misplaced.

In any event, I was excited on Saturday to write the above, because in stark contrast to a lot of the commentary I pen for this platform, it is all very straightforward and easily digestible by everyday investors.

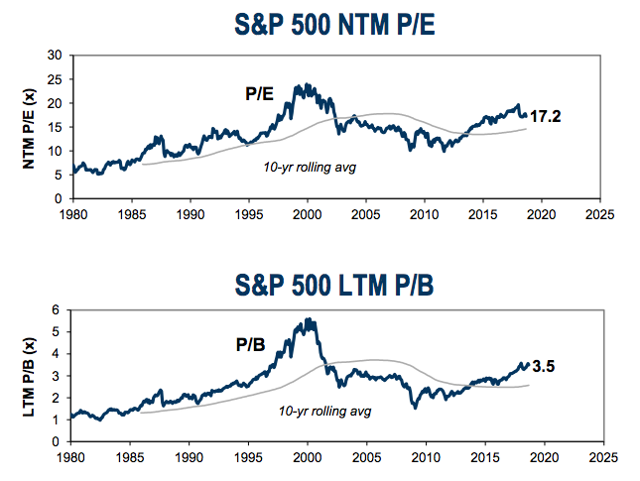

I would encourage you to think about everything said above as you ponder the relative merits of a market that is trading like this:

(Goldman)

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario