YUAN WEAKNESS ISN´T JUST ABOUT TRUMP / THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Yuan Weakness Isn’t Just About Trump

The real story on China’s currency has much bigger implications for investors

By Nathaniel Taplin

China no longer sells much more to the world than it buys. Photo: -/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

China, President Trump’s favorite trade target, produces too much and consumes too little. Right?

Not exactly. China no longer sells much more to the world than it buys these days, a key factor—alongside slowing growth and Mr. Trump’s ratcheting trade threats—behind the yuan’s 8% slide against the dollar since late April.

China’s narrowing trade surplus could enhance U.S. trade leverage, and eventually force wide-ranging changes in Chinese industrial policy. But nearer-term, it could make it harder for China’s central bank to keep the yuan, currently at 6.8 to the dollar, from breaching the totemic level of 7.

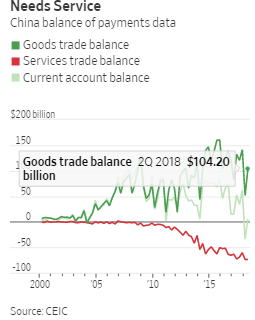

China’s current-account surplus last quarter was just $5.8 billion, well down from a quarterly average closer to $70 billion back in 2014 and 2015. The main reason: Net services imports have nearly tripled since late 2013, hitting $74 billion last quarter. It’s no great mystery why. Consumption accounted for nearly 80% of China’s growth last quarter, compared with less than 50% five years ago.

This underlying change in China’s trade position has some important implications. To prevent the yuan’s decline from becoming permanent, Chinese policy makers need to encourage more inward investment to offset rising consumption of foreign wares. They also need to keep Chinese capital at home. Otherwise, the central bank will have to spend more of its foreign-currency reserves to prop up the yuan.

Though there isn’t much sign of big capital outflow yet—China’s reserves barely budged last month—the central bank isn’t taking any chances. Last week it reinstituted reserve requirements for yuan forwards to make speculating against the currency more expensive.

The changing trade picture should increase Mr. Trump’s leverage over China. To keep exports to the U.S. from collapsing, Beijing may now be more willing to offer trade concessions. It may also be more willing to make investing in the country easier—particularly since China’s latest domestic growth stimulus has yet to kick it.

To make up for lower earnings from trade in the long run, keeping both domestic and foreign capital happy will be critical. That means boosting returns at home, a goal at odds with an industrial policy of shoring up inefficient state-owned giants at the expense of private companies. Real state enterprise reform may eventually become a necessity, not a choice.

Such policy shifts take time, however. The near-term risk is that as China keeps pushing domestic interest rates lower, large dollops of cash will start to find their way around the country’s strict capital controls. At that point, even the yuan’s recent sharp fall may start to look like a gentle decline.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario