This Year’s Big Disrupter: The Dollar

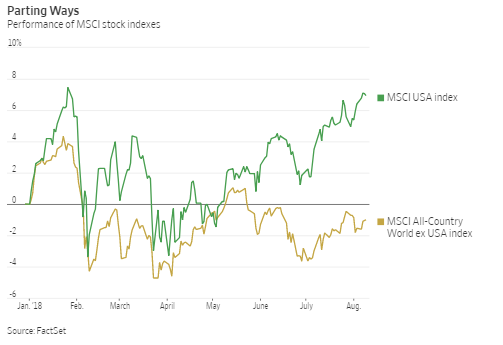

Lucrative trades were upended by the second-quarter rise in the dollar. Getting the greenback’s path right matters.

By Richard Barley

Much of the disruption to global financial markets this year has come from a source close to home: the U.S. dollar.

Investors obsess over stock indexes and bond yields but the most important number in financial markets may be the dollar’s exchange rate. That was clear when the dollar’s sudden rise in the second quarter derailed many moneymaking trades and changed the path of economies and industries. In some places, the pain is extending: The Turkish lira went into meltdown this week, sending ripples through global markets. Friday, the ICE dollar index hit a fresh one-year high.

The dollar’s rebound came after a broad decline in 2017, as growth outside the U.S. picked up.

That lured investors into riskier bets: the MSCI Emerging Markets stock index gained over 30%.

This year kicked off in similar style. But then U.S. growth vaulted higher and momentum stalled elsewhere, sending the dollar on an unexpected upturn. It gained 5.5% against the euro and 4.2% against the yen in the second quarter; moves in emerging markets were even bigger, with the greenback up 17% against the Brazilian real and 16% against the South African rand.

Nearly everything that surged in 2017 has wilted in 2018. After months of tumult, there is reason to believe the rest of the year will be calmer for the dollar, meaning less risky for emerging markets and other volatile assets.

The oddity is that much of the uncertainty about global growth has been generated by unorthodox U.S. policy, whether on tax, trade, or political alliances such as NATO. But even as the U.S. becomes the global disrupter, its assets have proved more alluring for investors. The dollar has kept its role as a magnet in times of doubt.

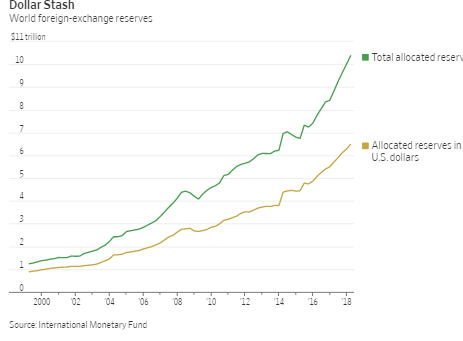

That is in part because the dollar remains so dominant. In the $5.1-trillion-a-day foreign-exchange market, the U.S. currency is on one side of 88% of all trades, according to the Bank for International Settlements’ 2016 survey. While its weight in foreign-exchange reserves has declined a little, it still accounts for 62.5% of the $10.4 trillion in allocated reserves identified by the International Monetary Fund. The euro, meanwhile, accounts for 20.4%. U.S. capital markets are the biggest and most liquid in the world, making the dollar attractive both to companies looking to raise finance and investors with cash to put to work.

The dollar’s path not only reflects changes in global growth, but can also steer them. Most notably, a rising dollar tightens financial conditions in emerging markets: It may lead central banks to raise rates to shore up their currencies, for example, or dampen the appetite of commercial banks to lend in dollars since their chances of getting paid back declines as the local currency falls. While floating exchange rates in emerging markets have reduced the risk of sudden explosive crises, they come at this cost.

The dollar’s performance in the second half could be less disruptive. Against major currencies like the euro, the greenback has stopped climbing. A good deal of divergence between growth and monetary policy in Europe and the U.S. already looks priced in.

Where the dollar’s strength has exposed weak links in emerging markets, it may continue to cause problems. For countries like Turkey, where the lira is down 36% this year, the problem now is homegrown, not external: There is a serious loss of investor confidence that wouldn’t be solved by a broad-based weakening in the dollar. The bigger picture will be influenced a good deal by the trade dispute between the U.S. and China and whether the Chinese yuan continues to fall, raising depreciation pressures on other currencies.

The dollar has rebounded after a broad decline in 2017. Illustration: photo illustration by WSJ; iStock (2)

For all that the dollar’s rise has accompanied stronger growth in the U.S.—with second-quarter gross domestic product expanding at a 4.1% annualized clip—there is a domestic downside.

Over time, a stronger dollar can hurt U.S. corporate profits as exports become less competitive and foreign earnings are worth less translated back into dollars. While tax cuts have boosted economic growth, they have also raised the budget deficit, which may lead investors to start thinking about the scale of U.S. borrowing.

The flip side could be a debate about whether assets denominated in other currencies are cheap enough to be attractive. Growth outside the U.S. has shown signs of stabilizing, and overseas stocks have started to rebound. A less disruptive dollar could, given time, add to the momentum beyond American shores.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario