THE RISE OF PRIVATE ASSETS IS BUILT ON A MOUNTAIN OF NEW DEBT / THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The Rise of Private Assets Is Built on a Mountain of New Debt

Credit businesses have helped drive the private-equity industry’s expansion but things could get awkward when companies hit trouble

By Paul J. Davies

CREDIT APPROVAL

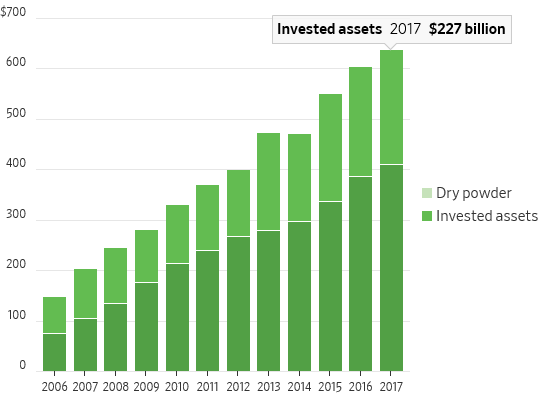

Assets under management in global private credit funds

In the world of private deal making, the biggest borrower in town is becoming one of the biggest lenders too. With so much money chasing buyout opportunities, big and risky deals seem the likely outcome.

A major change in financial markets in recent years is that private-equity firms have increasingly got into lending to buyouts, too—and often to their own deals. Their credit businesses are adding to the huge growth in specialist private debt funds and retail money that has taken place in loan markets since the crisis.

The flood of money into credit has driven down borrowing costs and cleared out traditional lender protections known as covenants on many loans.

POPULAR COMEBACK

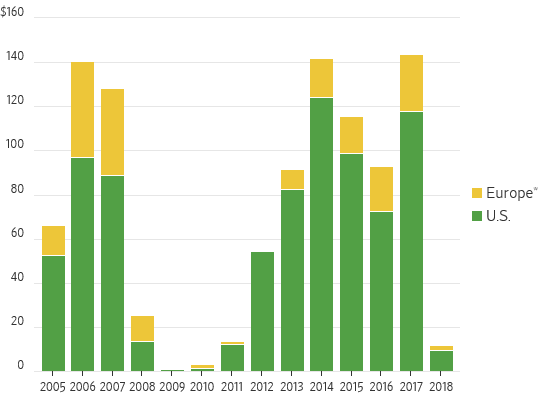

Issuance of collateralized loan obligations

It is also starting to lift debt multiples on newer deals. Blackstone’s recent deal for a controlling stake in Thomson Reuters’s financial information arm includes debt worth about 7.5 times earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization. That is approaching precrisis levels.

The growth of debt operations at firms like Blackstone, KKR and Apollo is an important part of their expansion. They can manage loans in private-credit funds, special vehicles known as collateralized loan obligations, or CLOs, and listed business development companies, or BDCs.

Private-credit funds run by major specialists like Alcentra or Hayfin, as well as the big private-equity firms, had nearly $650 billion in assets under management globally as of last June, three times more than in 2007, according to Preqin, the research firm. Retail loan funds manage about $100 billion. CLOs and BDCs add billions more.

Blackstone Chairman and CEO Stephen Schwarzman speaks in September 2017. Photo: Mark Lennihan/Associated Press

Investors like loans because they have floating interest rates—unlike bonds, which have fixed rates. That means loan investors don’t lose out when interest rates rise. But that can be bad for borrowers, who are hit by higher debt costs, especially if rates rise sharply.

Private equity’s growing involvement in private debt can make things awkward if a company gets into trouble and a firm’s credit and equity teams are on opposite sides of a workout.

Industry executives say their credit funds are never the lead lender to their own companies: That should allow their credit funds to take a back seat to the biggest lenders in any talks and avoid conflicts of interest. But their investors may still end up unhappy with the outcome.

PAYING UP

Default rates on U.S. leveraged loans

Apollo will buy the debt of companies it owns if they get into trouble, but uses the same fund that holds the equity. That avoids internal conflicts, but can provoke fights with others. Its ultimately profitable restructuring of Realogy , the U.S. real-estate brokers, for example, involved legal battles with other lenders.

Other firms invest separately. Blackstone’s credit funds don’t lend to its deals, but its CLOs can buy the loans of its companies. Carlyle allows its credit funds to take about 10% of its portfolio companies’ debt, while KKR allows up to 30%. The firms say their credit funds aren’t forced to buy debt if they don’t like the terms, nor do they influence the pricing to make the debt more advantageous for their equity funds.

The big firms’ private credit businesses are clearly adding to the volume of money chasing deals. As the market heats up this approach means they risk losing on the credit and equity side after the next buyout bubble.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario