Who Killed The Bull Market?

by: The Heisenberg

- "Bull markets do not die of old age."

- Ok, so what kills them?

- And if killing a bull market and/or an economic expansion is a crime, who's the culprit?

- Ok, so what kills them?

- And if killing a bull market and/or an economic expansion is a crime, who's the culprit?

As regular readers know, I am no fan of amorphous market aphorisms.

Here's a good rule of thumb: If it would be right at home in a market-themed tear-off desk calendar, it's probably not very useful for you as an investor.

Nebulous statements like "the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent" are great as punchlines or as something you would use as the last slide in a Powerpoint presentation delivered during an undergraduate finance seminar, but their universality serves to render them meaningless for making actual decisions about real money.

Take the "irrational/solvent" aphorism for example (because that's one that people trot out all of the time in an ill-fated effort to say something ostensibly profound). That statement is meaningless. Of course the market can "remain irrational longer than you can stay solvent."

And I say "of course" because the opposite of that statement could never be true. When would it ever be the case that the market could not remain irrational longer than you can stay solvent?

The only way that would be possible is if you were an immortal with unlimited funds. And even then it would probably be a stalemate because assuming your immortality doesn't apply in cases where the actual world ends, there's a scenario in which the market remains irrational while you remain solvent right up until a comet hits the Earth at which point the standoff between the market's irrationality and your solvency becomes immaterial by virtue of the fact that both the market and you have ceased to exist.

And I say "of course" because the opposite of that statement could never be true. When would it ever be the case that the market could not remain irrational longer than you can stay solvent?

The only way that would be possible is if you were an immortal with unlimited funds. And even then it would probably be a stalemate because assuming your immortality doesn't apply in cases where the actual world ends, there's a scenario in which the market remains irrational while you remain solvent right up until a comet hits the Earth at which point the standoff between the market's irrationality and your solvency becomes immaterial by virtue of the fact that both the market and you have ceased to exist.

See what I mean? It's meaningless by virtue of being self-evident. And most other market aphorisms are of a similar carácter.

Ok, so that brings me to the following quote from Goldman's latest "Top of Mind" piece. In that piece, there's an interview with Omega's Steve Einhorn and here's what Steve said when asked what could derail the bull market:

Neither economic expansions nor equity bull markets in the US die of old age.

That's another amorphous market aphorism that gets bandied about all the time and I'm not a fan of it.

Of course economic expansions and equity bull markets don't "die of old age." Neither do people. It's everything that goes along with being "old" that kills people and the same goes for economic expansions and bull markets. Again, there is no sense in which the opposite of that aphorism would ever make sense. Imagine, for instance, that you woke up on Monday, turned on CNBC, and heard this: "The U.S. economy careened into recession and global stocks plunged 10% overnight because both the expansion and the rally were deemed too old according to economists and traders." That doesn't make any sense, and so by extension, that aphorism is useless.

Now to be fair, there is a certain sense in which things that are self-evident are useful. After all, we can't dismiss things that are by definition true, because at the end of the day, we're all out to discover the truth. But there's no utility in parroting the self-evident. That doesn't get us anywhere. Self-evident statements are nice as reminders when our thinking has become detached from reality and that thinking is materially impacting our lives, but that's about as far as it goes. So for instance, if you keep buying OTM puts in anticipation of a market crash and after two years of doing that and seeing them expire worthless you are having trouble buying food and paying the electric bill, well then, you might benefit from an amorphous aphorism about market irrationality outlasting your solvency or about how bull markets do not come with expiration dates. But outside of that, these oft-repeated nuggets of market "wisdom" are largely useless.

So the reason I bring that up is because in the interview mentioned above, Einhorn embarks on a quest to explain that why the current expansion and bull market have not yet manifested themselves in the type of "symptoms" (if you will) that would normally precede death. As noted above, it's everything that goes along with being "old" that kills people and the same goes for economic expansions and bull markets.

Steve looks for (and ultimately finds) evidence to support the contention that we are not in fact late cycle (as many people claim) but rather mid-cycle. So you can think of this as something akin to a 97-year-old getting a physical and the doctor concluding that while 97 is indeed a nominally high number, physically speaking there are no signs that death is imminent. The things that go along with being old which eventually kill people have not as yet caught up to the person.

Einhorn does an admirable job in this regard. Here's what he says about the expansion:

There is an almost unending number of metrics that suggest we are more mid-cycle than late-cycle in economic activity. The GDP gap, which measures output versus potential, has — almost without exception — been above zero and declining before we entered a recession during the last 40 or 50 years; today, it is below zero and rising.

The share of cyclical components of GDP — consumer durables, residential investment, capital spending — is typically above average late in an economic expansion, but today it is below average. The Conference Board’s leading economic indicator composite is typically declining year-over-year six to nine months before the beginning of a recession, whereas it is currently up. The unemployment rate is typically up year-over-year late in the economic cycle, but it is now down. Inflation usually accelerates late in the cycle, but today it is moderating. Real money supply growth typically sinks late in the cycle, but it is now stable-to-growing. The fed funds rate is typically above Fed estimates of the neutral funds rate when we are late in the cycle, but today the funds rate is probably less than half of the neutral rate. The yield curve typically has a flat-to-negative slope late in an economic expansion, but currently the slope is positive. And credit spreads, which normally widen prior to the end of an expansion, are tight and stable-to-narrowing. I have more examples, but I think those are enough to indicate that we are nowhere near a recession, that the probability of a recession anytime soon is quite low, and that mid-cycle characterizes the current economy better than late-cycle.

And here's what he says about valuations:

Equity valuations are not at all stretched given the low level of interest rates. Today, the S&P 500 (SPY) earnings yield is 5.5% while the 10-year Treasury yield (TLT) is less than 2.5%. This is a very wide spread relative to history. Further, the composite yield of the S&P 500 — dividend yield plus buyback yield — is very high relative to bond interest rates. So it is nearly impossible to suggest that the S&P multiple is extended relative to rates on Treasury bonds, investment grade bonds, or high yield bonds. Of course, absolute measures of value such as market-cap-to-GDP, price-to-sales, or the Shiller price-to-earnings ratio are all at the very upper end of their historical ranges. But importantly, there is virtually no correlation between such measures and S&P 500 returns one, two, or even three years out. So it’s not relevant to an investor to say absolute measures are extended. Finally, valuation by itself does not end bull markets.

Ok, so all of that is great and there's no question that these are the types of arguments we need when it comes to having serious discussions about whether the cycle is about to turn and/or about whether a correction in risk assets is just around the corner.

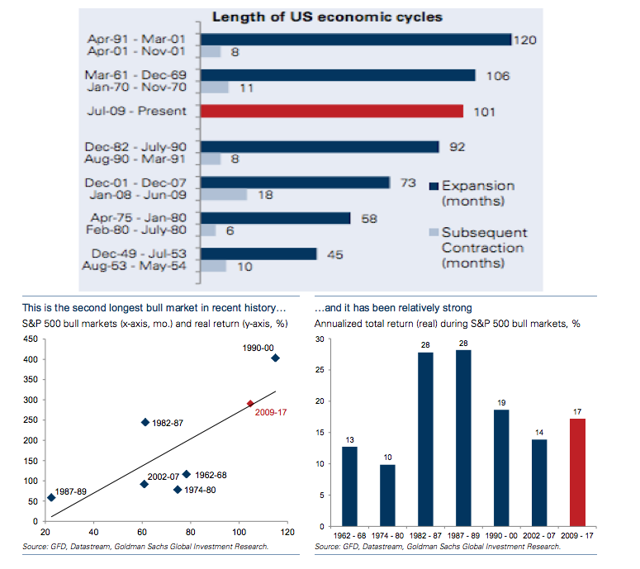

And the reason I say that is because a cursory look at the current state of affairs overwhelmingly suggests that we are teetering on the edge in terms of pushing the historical limits on both the length of the expansion and on the scope of the bull market:

(Goldman)

Cursory looks are just that - cursory. A cursory examination allows us to get a general sense of the current state of affairs. Once we have a general idea of the situation, we can then determine who has the burden of proof. Clearly, the burden of proof when it comes to predictions about the current expansion and the rally lies with those who say that one or both will continue. That might seem counterintuitive, but it's not. The very use of the term "cycle" implies that a downturn is inevitable.

The very idea of a bull market implies that there is some state of affairs that exists which is not a bull market. And so, when expansions and bull markets reach historical extremes in terms of length and scope, it is incumbent upon those who contend that history is not a good guide to explain why.

The same thing is true in the opposite direction. During contractions and prolonged bear markets, there comes a point at which anyone who is still bearish must explain why history is wrong to suggest that the economy will turn around and/or that stocks will not simply go to zero.

In this scenario, you cannot fall back on aphorisms. "Expansions and bull markets do not die of old age" doesn't work, because as noted above, that's self-evident. Assuming everyone realizes it's self-evident and thus not worth assailing in defense of a bearish position, the bears must be arguing something else - namely that while old age itself doesn't kill expansions and bull markets, the things that accompany old age do.

But let me save you some trouble. Getting into a metrics arms race with market veterans is an exercise in abject futility. For one thing, metrics are in many cases vulnerable to tedious critiques about the extent to which they are more or less meaningful "this time" than "last time." And on top of that, one person's list of purportedly definitive metrics is going to be different from another person's list. So that argument ends up devolving into something akin to a debate about who the top five NBA players of all time are. Everyone has a claim on being "right."

The better way to critique Einhorn's assessment is to point out the obvious: his arguments about the expansion and about valuations are contingent and relative, respectively. In short: his assessment depends to a large degree upon inflation remaining anchored and relatedly, upon central banks remaining gun-shy. He readily acknowledges this as follows:

Neither economic expansions nor equity bull markets in the US die of old age; they are murdered by the Fed.

That effectively relegates all of the points enumerated in the first two excerpts cited above to also-ran status. It doesn't mean they aren't useful and it sure doesn't mean I can refute them all (I can't), it just means they are secondary and thus will be largely immaterial in the event the Fed's hand is forced.

Consider these excerpts from the same interview:

It’s certainly a unique cycle, for several reasons [one of which is that] inflation has been much tamer than in other expansions.

The start of bear markets in the US — almost without exception — has historically required five conditions that we have put on a “bear market checklist.” And none of these conditions are present today, nor do I expect them anytime soon. The first item on the list is problematic wage and consumer price inflation, by which I mean inflation that would likely illicit an aggressive response from the Fed. I would put problematic wage inflation at about 3.5% to 3.75% year-over-year and problematic core consumer inflation at around 2.5% year-over-year, or maybe a touch higher.

And see there it is: everyone keeps coming back to the same point. Namely that all of this hinges on inflation never showing up. But everything central banks have done since the crisis has ostensibly been in the service of creating inflation. Further, the fiscal agenda in the U.S. (if it ever gets implemented) is geared towards reflation.

The snail's pace of policy normalization in the U.S. (and especially in Europe and Japan, with the latter having not even begun to tighten) has in large part been justified by the fact that inflation has yet to materialize in the way you might expect it to given how long accommodation has remained in place. Recall this from Albert Edwards' latest:

Indeed throughout this cycle wage inflation has been the dog that failed to bark.

The risk is that the market is hugely vulnerable if it hears a distant bark, let alone feels its bite.

The longer this goes on (i.e., the longer inflationary policies are pursued without inflation actually showing up), the greater the risk that everyone is missing something. Here's Edwards one more time:

The nightmare scenario for equities would be if US wage inflation flickers back to life and investors not only decide that they are too far behind the Fed dots, but they also decide that the Fed itself is behind the tightening curve.

In that event, everything goes out the window. All bets are off. Because we've never been here before. This experiment in monetary policy is unprecedented.

What seems to be at least partly lost on everyone parroting the "expansions and bull markets don't die of old age, they are murdered by the Fed" line is that if what you've seen in the past in that regard can be accurately described as "murder," well then, what you're going to see this time around will be an outright "massacre".

Finally, allow me to pose a question in closing: what happens if inflation "starts to bark" at the same time that fiscal policy finally loosens and the post-crisis regulatory regime is dismantled?

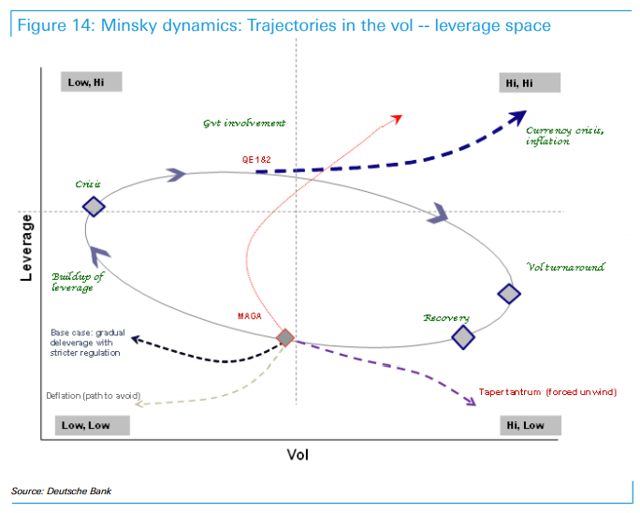

Here's a hint (follow the red line from the lower left quadrant to the upper right)...

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario