How Tether became money-launderers’ dream currency

The stablecoin is fuelling a global shadow economy. And it’s never been more respectable

By Oliver Bullough

What may be the most consequential cryptocurrency investigation in recent times began on a November evening in 2021 in a defiantly offline location: the southbound carriageway of Britain’s M1 motorway.

Metropolitan Police officers suspected a driver was carrying illicit cash, and pulled him over as he approached London.

Bodycam footage shows the driver, Fawad Saiedi, sitting in the backseat of an unmarked police vehicle, his hands cuffed in his lap, a slightly sullen look on his face, while two officers search the boot of his car.

Their tip-off had been accurate.

The officers found more than £250,000 ($340,000) in cash, each bundle of notes wrapped with the denomination it contained – mostly tens and twenties, with a few fifties thrown in.

Police officers were pleased with the haul, but well aware that it was only a small victory in their campaign against organised criminals.

The drugs trade in Britain generates £10bn a year, so this bust didn’t even amount to 1% of a single day’s takings.

It was what they found on Saiedi’s phone that transformed his arrest from another footnote in the never-ending war on drugs.

“We inadvertently turned over a stone, and went down the deepest, darkest hole for three years,” said William Lyne, head of cyber-intelligence at the National Crime Agency (NCA).

Drug gangs all over the world face the same problem: how to make use of their cash.

They can’t just deposit notes in a bank, owing to rules against money-laundering, so they need to find someone to take the money off their hands and render it clean.

Police officers knew that Saiedi would be part of a bigger organisation tasked with moving dirty money back into the legitimate economy.

But when they discovered who he was working with, they were astonished.

Ekaterina Zhdanova is a Russian businesswoman, originally from Siberia.

A glamorous socialite, she promoted her own luxury watch brand, and was reported to have the personal motto: “Love yourself. Appreciate yourself. Look only forward and dream”.

To worldwide law-enforcement authorities, however, she was becoming known as someone who helped computer-hackers spend their money.

When ransomware gangs extort money, they are typically paid in cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin.

Bitcoin has a publicly available ledger, which means anyone can track the path of money from one digital wallet to another, even though they may not know the real-world identities of recipients.

This makes it hard for successful hackers to enjoy their loot below the radar of law-enforcement.

Theoretically, they could cash out their tokens at an official crypto-exchange, but large sums would draw unwelcome attention.

This was where Zhdanova came in.

She and her associates laundered the hackers’ money.

They reportedly worked in the tallest skyscraper in the Federation Tower complex, a vast 97-storey middle finger on Moscow’s skyline where many of Russia’s most notorious cyber-criminals are reputed to operate.

(Zhdanova’s lawyer declined to comment on this story.)

On Saiedi’s phone, police found direct messages from one of Zhdanova’s associates.

How could a British street gang be so closely connected to a Russian cybercrime influencer?

The subsequent investigation, known as Operation Destabilise, would last for years, draw in other law-enforcement agencies in Europe, the Middle East and America, and expose the contours of a hidden global economy.

It turned out that Britain’s drug gangs and Moscow’s hackers were just two nodes in a vast criminal super-network that Zhdanova was connecting.

It also included sanctioned oligarchs, Russian intelligence operatives and an Irish crime family.

The infrastructure underpinning Zhdanova’s operations was a cryptocurrency called Tether.

Tether’s technology and business model allowed her to bring various underground economies together, to their mutual benefit.

Her operation washed the drug gangs’ money, while assisting Russian clients in moving theirs.

Just a month after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, she made it possible for an oligarch to get hold of $2.3m in western Europe.

A little later, she helped another move more than $100m to the United Arab Emirates – and these were just trades that were known about.

If Zhdanova had tried to move that much in banknotes, the consignments would almost certainly have been intercepted at borders.

If she had tried to use the traditional financial system, banks would have noticed she was dodging sanctions and frozen the transfer.

Converting the cash into a cryptocurrency such as bitcoin would have helped her evade these checks, but it was an expensive and unreliable option.

Tether, however, is cheap to move.

It is a stablecoin, meaning it’s pegged to conventional currency.

One of Tether’s tokens (which are referred to either as “tethers”, with a lower-case “t”, or by their ticker symbol, “USDT”) is always worth one dollar.

You can use it as you would a dollar, but without any of the checks and scrutiny that come from moving actual dollars around.

It is the financial equivalent of being able to turn up at the airport, open a secret door and go straight on to the plane, without any X-rays, passport inspections, customs controls or intrusive questions.

There aren’t many other products that are as useful to criminals, and as much of a threat to the financial system, that have been allowed to flourish with so little regulation.

When asked about money-laundering concerns, Tether said the company was “fully committed to combating illicit activity”, and that it had frozen $2.5bn in illicit assets.

In 2024 the company issuing tether made profits of more than $13bn, almost twice as much as BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager.

Considering it has only around 150 employees, Tether may well have the highest profit per employee of any company ever.

It claims to have nearly half a billion users, and new ones are joining all the time.

While the company “unequivocally condemns the illicit use of stablecoins”, the further it spreads, the more useful it becomes to criminals.

For a brief period, Western countries looked like they might crack down on stablecoins.

In October 2024 the Wall Street Journal reported that American prosecutors were investigating whether Tether had been used “to fund illegal activities such as the drug trade, terrorism and hacking – or launder the proceeds generated by them” (Tether denied any knowledge of such a probe).

But this already feels like news from another world.

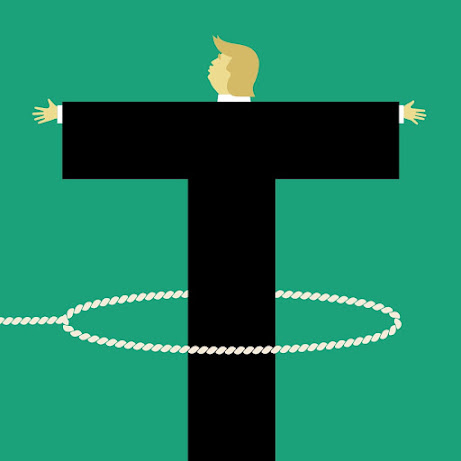

To say the Trump administration has embraced cryptocurrency is an understatement.

Since being re-elected to the presidency in November 2024, Donald Trump and his wife have both launched memecoins ($TRUMP and $MELANIA) and the United States has committed to creating a strategic reserve of bitcoin.

Yet it is his relaxed attitude to stablecoins that is arguably the most worrying shift in crypto policy.

Stablecoins like tether share the same underlying technology as cryptocurrencies like bitcoin.

But they work in a completely different way.

Tether, the most widely used, enables people to store their money somewhere safe and move it between countries seamlessly.

In this respect it functions less like a currency and more like, as one expert put it to me, “a totally unaccountable underground bank”.

Tether was conceived when enthusiasm about crypto was just starting to bubble up.

The first cryptocurrency, bitcoin, had appeared in 2009, along with its revolutionary decentralised blockchain – a collectively maintained, public ledger of transactions.

Enthusiasts saw bitcoin as a revolutionary tool which would free humanity from greedy banks, profligate governments and inefficient payment mechanisms.

Other cryptocurrencies followed, driven by the same idealism and passion.

But even their biggest supporters had to admit that they had problems.

Getting money into crypto often involved trusting shady intermediaries who might run off with it, while getting your money out again was likely to provoke unwelcome questions from your bank.

Furthermore, the value of currencies like bitcoin can jump around wildly, sometimes driven by nothing more than a prominent supporter’s tweet.

In 2014 the founders of Tether – since identified as a trio of crypto-enthusiasts which included a former child actor – invented the stablecoin: a cryptocurrency that was always worth a dollar.

They incorporated their company in the British Virgin Islands.

Owners could use tether to buy and sell cryptocurrencies, without having to worry about moving money to and from their bank accounts.

Tether’s founders intended it to help funds flow into bitcoin by providing a secure and reliable instrument which was halfway between a traditional currency and the money of the future.

The company guaranteed that every Tether token would always have a dollar’s worth of traditional assets to justify its value.

Many observers were sceptical about this, including New York State authorities.

In 2021 the state’s attorney-general fined Tether for misrepresenting its finances (the company did not admit wrongdoing, but agreed to pay).

People continued to buy Tether tokens nonetheless, and over the next four years the amount of deposits the company received increased by more than $100bn.

“Our product is so simple that it can be used by anyone.

It’s so inclusive,” said Paolo Ardoino, Tether’s chief executive, in a podcast interview last year.

“We can remove all intermediaries that are taking advantage and taking a bit from every single transaction, multiple bites from every single transaction…All those things will be crushed by stablecoins.”

This sounds good, until you think about what those “intermediaries” actually do.

Bankers, lawyers, accountants and others involved in the conventional financial system are under onerous government restrictions to keep criminals and terrorists out of it.

They are obliged to report suspicious transactions to the authorities and fined heavily if they don’t.

The global finance industry now spends more than $200bn a year complying with the laws that have been put in place over the last five decades to stop money-laundering and financial crime.

Banks report tens of millions of transactions to their in-house financial-intelligence units and block many of them while they’re being checked.

Tether cuts out this entire system.

It was originally intended as a gateway to the crypto ecosystem, but it proved to be far more than that: it set money free.

Zhdanova’s scheme was both intricate and stunningly simple.

First, her army of couriers collected cash from criminals across western Europe, who had earned it selling drugs or other illegal products.

They identified themselves to each other by the time-honoured “token method”, whereby a courier texts the criminals the serial number of a low-denomination banknote in his possession, then hands over the banknote itself when they meet, so the gang can be sure the person taking their cash is who they say they are.

Between 2022 and 2023 Zhdanova’s team collected more than £12m from British criminals alone.

Next, the couriers delivered the cash to oligarchs, espionage agencies, propaganda outlets and Russian expats who needed to pay for stuff but had lost access to the global banking system because of sanctions.

In the third stage, the recipients of the cash paid Zhdanova from their bank accounts in Moscow.

But this left a debt from Zhdanova to the British drug gangs who had handed over their cash.

She settled that debt with USDT (of which, as it happened, she already had a great deal because she was taking ransomware gangs’ bitcoin tokens off their hands and converting them into tether).

Zhdanova would use USDT to transfer money from a digital wallet in one country (such as Russia) to a digital wallet in another (such as Britain) as if international borders didn’t exist.

The drug gangs would use the cryptocurrency to buy cocaine from exporters in a third country (such as Colombia), and the whole cycle would begin again.

“This is the new money-laundering,” said Lyne, the NCA officer.

“We knew about lots of elements of this laundering activity in isolation.

But I think what Operation Destabilise does is bring it together as a whole in a coherent way, and you can understand how this global system works.

And that’s new to us, actually.”

One of the many surprising things about the scheme was how cheap it was to run.

Money-launderers traditionally ask for at least a 10% cut of the sums they are cleaning. As far as British law-enforcement analysts can work out, Zhdanova was charging her clients less than 3% on each transaction.

Tether’s efficiency makes money-laundering so easy anyone can do it.

In March Ardoino posted some photos to his Instagram account which looked like a set of holiday snaps.

In one of them, the Washington Monument was a distant needle over his right shoulder.

In another he was on the steps of the Capitol, the shadows sharp in the low spring sunlight.

Ardoino, a crypto-expert who joined as chief technology officer in 2017 before rising to become the public face of the company six years later, is a handsome Italian who dresses in stealth-wealth casuals.

He speaks enthusiastically about what Tether does, without the jargon and arrogance often displayed by the promoters of other cryptocurrencies.

One picture he posted in the Washington series was a bit different from the others.

He was standing on a highly polished checkerboard floor.

Behind him was a door.

The caption didn’t give much away – “WH Visit”, followed by an American flag – but the door looked a lot like the one that leads to the White House’s Blue Room, the oval chamber where presidents formally greet their guests.

Ardoino seemed to enjoy cultivating ambiguity about what he had been doing in the White House.

“That was my first trip in the United States ever.

I’m very thrilled to be here, and I love the country, and I had to do a little bit of photo-taking around the capital,” he told Bloomberg playfully a few days later (he later said that he had never met Trump).

Whatever the details of his itinerary, his trip underscored the fact that Tether was charting a course into the mainstream.

It wasn’t long ago that the company was operating on the fringes of respectability.

The Biden administration used to talk about how the stablecoin was used by terrorist groups, the Russian government and other foes to circumvent sanctions.

Financial-transparency campaigners hoped momentum was building towards a tougher approach to crypto.

In those days Ardoino would have been a fool to change planes in an American airport, let alone embark on a charm offensive of the capital.

And yet, six months later, he was pushing on an open door.

There has been no more talk of a Treasury investigation since Trump came to power, and the administration has enthusiastically embraced cryptocurrencies of all stripes.

After Washington, Ardoino moved on to New York for a technology conference organised by Cantor Fitzgerald, an investment bank which manages much of the huge store of assets that Tether uses to guarantee USDT’s value.

Ardoino was cheered as he took the stage in khakis and a tight blue sweater rolled up past the elbows.

“We’ve been through hell,” he said, according to one media report from the event.

“People were saying that if I came to the US, I’d be arrested.”

He talked about his company’s plans to invest in artificial intelligence, education and other projects.

Ardoino uses every opportunity he can to object to suggestions that Tether’s primary users are money-launderers.

On the contrary, he says, the cryptocurrency provides banking services to people in poor and badly governed countries who have never before had access to a stable currency or a secure savings account.

He is right that access to the formal financial system can be very difficult and expensive for people in developing countries.

If they work abroad and want to send small remittances to their families for example, money-transfer companies will typically take a cut of about 10%.

A tether transaction costs just a fraction of that.

Tether has made it easier for ordinary people to access USDT, constructing kiosks where people can buy or sell Tether tokens with banknotes.

You convert your dollars, pounds or euros into tether, then transfer the tether to your mother on the other side of the world; she converts it into the local currency and can spend it on food, rent or anything else, without the banks keeping a big chunk of what you’ve given her.

Who wouldn’t want that?

It’s a good deal for Tether too.

People give the firm real dollars, which can be invested in interest-bearing assets, and receive in exchange digital dollars, which cannot.

That means all the income from $155bn’ worth of assets accrues to Tether.

Such profits have enabled it to buy a stake in Juventus, an Italian football club (whose largest shareholder is also the largest shareholder in The Economist Group).

Tether has also invested three-quarters of a billion dollars in Rumble, a video-sharing website favoured by the far right.

Mostly Tether keeps its money in the safest investment that there is: US Treasuries.

In January 2025 it owned bills worth $113bn.

If Tether were a country, it would be between South Korea and the United Arab Emirates in the list of foreign holders of American debt.

It was probably not, therefore, the inclusiveness of Tether’s technology that persuaded Cantor Fitzgerald to start working with it in 2021, but its extraordinary profitability.

Cantor does more than manage Tether’s dollars – it has a convertible bond in the company, a form of debt that can be changed into an ownership stake.

The Wall Street Journal has reported that the potential stake could be as high as 5%.

The two companies also launched a bitcoin-buying joint venture in April.

The connection to a big New York financial institution like Cantor Fitzgerald lent respectability to Tether, and even more so when Cantor’s boss, Howard Lutnick, became Trump’s commerce secretary (he has since handed control of the company to his sons).

Before Lutnick’s confirmation hearing, Senator Elizabeth Warren sent him a long letter detailing the allegations made against Tether, mentioning concerns about the cryptocurrency’s usefulness to money-launderers.

He dismissed these as unfounded.

“It’s like blaming Apple because criminals use Apple phones.

It’s just a product,” Lutnick said in the hearing.

The argument for USDT not being a bad thing has remained roughly the same since the product’s launch, but the argument for it being a good thing has evolved.

At first it was the gospel of financial inclusion.

Since Trump’s return to the White House however, Ardoino has also been stressing how useful Tether is as a funder of American debt and an instrument of American power.

He warns that China is planning to launch a cryptocurrency of its own, perhaps linked to the price of gold, which could be used to finance the country’s trade transactions and thus dethrone the dollar.

The spread of Tether’s USDT, Ardoino argues, is helping to keep such threats at bay.

“We represent the most important use case for the US dollar hegemony around the world,” he told Bloomberg in March.

“We are present, with boots on the ground, building infrastructure for the US dollar from the ground up in all the emerging markets. I believe that USDT is representing the last stronghold for supporting the US dollar.”

Trump administration officials seem to share his enthusiasm for stablecoins, and recently rushed through legislation to clarify the legal and regulatory framework they would be operating in, to encourage growth in the sector.

The House and Senate bills (which have been given the acronyms STABLE and GENIUS) still need to be reconciled with each other before they can become law, so the precise nature of the enforcement powers they’ll give federal agencies is still not clear.

Either way they won’t affect Tether much since it is not based in the United States.

In January the company moved its headquarters from the British Virgin Islands to El Salvador – Ardoino said that the government of Nayib Bukele shared his vision of financial freedom.

One of the biggest holders of American debt in the world is now under the jurisdiction of a man who has described himself as “the world’s coolest dictator”.

To get a better sense of the new attitude towards cryptocurrencies, I flew to Washington, DC, earlier this year for the annual Blockchain Summit.

It was held in an industrial-chic conference space, all exposed concrete and long queues for the coffee.

Up a flight of stairs was an exclusive networking area sponsored by Tron, a blockchain network.

Ordinary attendees were privileged by the sight of the VIPs’ legs as they mingled.

Some of America’s most important regulators were there too: congressmen and senators, the governor of Wyoming, and several of the crypto world’s most powerful people.

In the main conference hall, Senator Tim Scott, a Republican from South Carolina and chair of the Senate’s banking committee, conducted the audience in a theatrical booing of the previous administration.

Tom Emmer, the whip for the Republican majority in the House of Representatives, criticised Biden’s attempts to prosecute people for creating technology: they weren’t to blame for what people did with it.

“I’m so excited for all of us, right?

This has been a long road to get here.

We are on the precipice of actually making this happen.

And guess what?

That’s only the beginning.”

The audience enthusiastically applauded.

Attendees were on a sliding scale of coolness: the founders wore hoodies, the investors had their shirts open, but most people were fully suited, and wore the lanyards of law firms around their necks.

They rarely if ever entered any of the sessions, but exchanged business cards and discussed data-centre contracts in the hallways.

The presence of this many lawyers is usually a good indicator an industry is about to take off.

There were some Democrats at the conference, including three congressmen who addressed a sparsely attended side-event about keeping crypto bipartisan.

But attendees were largely pro-Trump.

The star of the conference was Donald Trump junior, who, together with other family members, runs World Liberty Financial (WLF), a crypto company that has issued its own stablecoin.

Donald junior joined remotely, so his vast face loomed on a screen over the stage like a perma-tanned deity.

He explained how his own experience of suffering discrimination made him a true believer in the power of cryptocurrencies to democratise finance.

By cutting out the intermediaries and the greedy, overpaid bankers, WLF will be able to provide cheaper, better financial services for everyone, according to him.

“It’s the future of our financial systems, and I want to make sure that’s domiciled in America, done by Americans,” he said.

“If we can make it easy to use, this is a no-brainer, and I think we’re there, we’re on that cusp.”

I bumped into two veteran financial journalists after his session had ended, and the three of us stood in the hallway while the lawyers flowed around us, like atheists at a religious revival, looking for the words to express our bewilderment.

“What the fuck is going on?” one asked, but no one had an answer.

In August last year Tether teamed up with Tron and TRM, an investigations company, to launch “a financial crime unit”.

T3, as it is called, aims to help law-enforcement agencies stop illicit wealth moving via USDT.

I saw Ardoino talk about T3’s progress when he was beamed into the Blockchain summit via video link.

He gave a standard homily on how Tether transactions made the job of law-enforcement easier by providing a transparent ledger.

“With blockchain technology, actually, everything is there,” he said.

“You cannot tamper with the history of transactions.”

This is true, though the transparency doesn’t do much to limit the flow of dirty money, since it moves so fast it will have disappeared before anyone tries to stop it.

The most realistic use of Tether for law-enforcement officials is in providing an accurate account of where criminal wealth used to be.

Looking proud, Ardoino enumerated the law-enforcement requests T3 has responded to, and pointed out that its team of “20 or 30” investigators has frozen tens of millions of dollars’ worth of Tether tokens.

This sounds impressive until you compare it with the compliance work done by conventional financial institutions.

A major bank such as HSBC employs thousands of compliance officers, a total several times larger than Tether’s entire workforce.

Tether brings in 40m new customers every quarter, and there is simply no way that 20 or 30 investigators could check all these customers’ bona fides.

“Tether talks a good game,” said one crypto analyst.

“But their actions don’t mirror that in my experience.

The vast majority of illicit activity and crypto assets have switched to Tether in recent years.”

There is something strange about Tether claiming credit for responding to law-enforcement requests at all. In a recent interview with Bloomberg’s “Odd Lots” podcast, Ardoino sounded almost like a head of state, weighing up which alliances to form.

“We need to work primarily with US law enforcement, law enforcement, and we tend to not work with tyrannical countries’ law enforcement,” he said.

But financial institutions are not supposed to be able to choose which countries they help with information.

If they operate in a territory, they are subject to that territory’s rules.

The problem for law enforcement is that Tether and other stablecoins operate in a cloud beyond the nation state – which means that governments are left begging them for information, rather than forcing them to comply.

Tether is prickly about criticism (it has called the Wall Street Journal’s reporting on it “wildly irresponsible”) and law-enforcement agencies are reluctant to speak against the company even if they don’t need its co-operation currently, in case it comes back to haunt them when they need it in the future.

The number of schemes which a law-enforcement officer might need Tether’s help to unravel is proliferating by the day.

Zhdanova herself may now be in prison – she was arrested by French police at the end of 2023 as she passed through Nice airport – but the stablecoin is reported to have been key to the “pig butchering” romance scams of South-East Asia, the operations of North Korean hackers, and the financing of terror groups.

Law-enforcement officials simply have to hope they get lucky, as they did with the courier bust on Britain’s M1, and stay on the right side of Big Crypto.

“Stablecoins are a money-launderer’s dream,” said one.

“But we don’t want to say that in public because we do not want to ruin our relationship with Tether.”

Oliver Bullough is the author of “Moneyland” and “Butler to the World”. His new book, “Everybody Loves our Dollars” will be published in 2026

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario