Peru’s illegal gold-mining crisis

Fraser McIlwraith

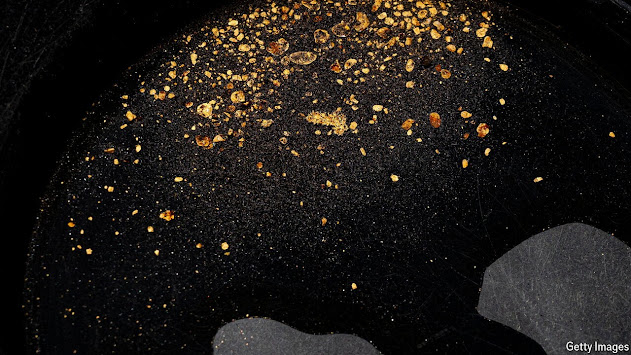

Gold has a violent history in Peru.

When I travelled there last month to report on a boom in illegal gold-mining, a story from the country’s past stuck in my mind.

In 1532 Francisco Pizarro, a conquistador, captured Atahualpa, the Inca emperor. Atahualpa offered to fill a room with gold as a ransom.

The Incas gathered some 24 tonnes of gold and gave it to Pizarro, who killed Atahualpa anyway.

The Gold Museum of Peru, tucked in the basement underneath a giant museum of weapons in Lima, the capital, captures something of that history.

To see its radiant collections, I first had to walk through gloomy corridors lined with pikes, armour and guns.

The two exhibitions were a stark reminder of the intertwined nature of gold, conquest and brutality in Peru.

Violence has swept through Peru’s illegal gold-mining industry in recent months.

In early May, 13 security guards who worked in a gold mine near Pataz, a hardscrabble mining town in the northern Andes, were kidnapped and shot dead.

The perpetrators shared videos of the murders on social media.

Mass graves and dynamite attacks, thought to be the work of mining gangs, have also been reported.

Almost everyone I spoke to in Peru thinks the scourge of mining gangs is getting worse.

Víctor Fuentes studies illegal gold-mining at the Peruvian Institute for Economics, a think-tank.

He says Peruvians now joke that the country is closer to becoming like Colombia in the 1980s, when gangs ruled much of the country, than it is to joining the OECD, a club mainly of rich counties.

Illegal gold-mining takes different forms in Peru.

During the 2010s so-called “wildcat” miners tore up swathes of the Amazon in defiance of environmental laws.

But the recent spread of illegal mining in places such as Pataz shows the extremes which gangs will go to gain control of mining areas.

There are several reasons for the worsening crisis.

The first is the surging price of gold, which passed $3,000 an ounce in March.

Another is a coca glut, which pushed down wholesale prices and encouraged drug gangs, who use the plant to produce cocaine, to branch out into other activities.

These two factors lie behind a surge in illegal mining across the Amazon and the Andes.

But in the case of Peru, successive governments have made the problem worse.

Disastrous formalisation policies have acted as a shield for mining gangs.

One scheme, Registro Integral de Formalización Minera (REINFO), was introduced in 2012 to allow small-scale, informal miners to bypass certain restrictions as they moved towards joining the regulated mining sector.

Only a tiny fraction of registrants actually complete the formalisation process.

But despite this, and after several extensions, the policy remains.

Two weeks after the killing of the security guards in Pataz, I met some informal miners at a protest in Trujillo, a city on Peru’s northern coast.

The government had just imposed a 30-day ban on many mining activities in the province in response to the murders, putting hundreds of small-scale miners out of work.

Surrounded by the candy-coloured colonial buildings of the city’s main square, they were demanding to return to work.

Many held placards that denied any connection between informal mining and criminal gangs.

“We are informal miners and not criminals,” read one.

Others were angry that the president, Dina Boluarte, had ordered a broad ban on mining rather than targeting the gangs.

The crowd was subdued; behind their riot shields, the police looked bored.

But tensions were high.

A few days ago the ban in Pataz ended, though a state of emergency and curfew remain.

REINFO is supposed to expire at the end of this month, but analysts predict the government will extend it until at least the end of the year.

Maintaining this status quo does nothing to deal with Peru’s mining gangs.

Nor will it help the country’s informal miners, who will keep campaigning for REINFO (however poorly it helps them to formalise) to be extended—at least, until the government comes up with something better.

With Peru’s politics set to remain gridlocked until the election next year, no progress is likely to be made soon.

The future of the country’s gold, like its past, looks dark.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario