A Shrinking China Scrambles for a New Economic Model

A declining, aging population is a poor foundation for consumption-driven growth.

By: Victoria Herczegh

China is shifting from an export- and investment-driven economy to one based on domestic consumption.

The reason is persistent economic stagnation and a growing risk that the country will fall short of its growth targets.

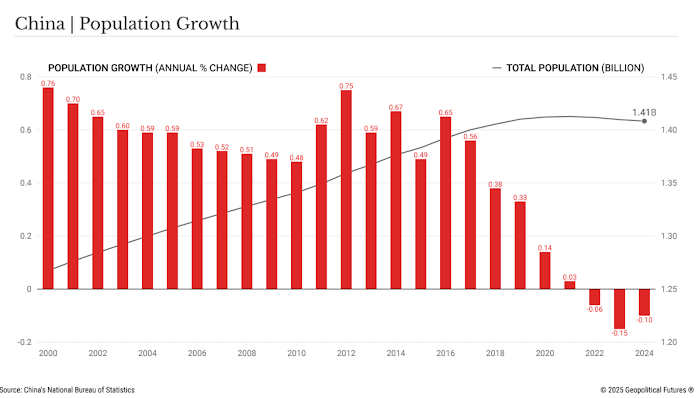

In the past, China could rely on its large and steadily growing population as a foundation for economic advancement, but now its population is aging and shrinking rapidly.

A full transition to a consumption-based model appears out of reach for now, partly due to the demographic decline.

In fact, consumption has trended in the opposite direction in recent decades, falling to 53 percent of gross domestic product in 2022 from more than 63 percent in 2000.

However, with trade tensions deepening and foreign direct investment drying up, boosting consumption is the only viable alternative to China’s dysfunctional investment-driven model.

Successful to a Fault

According to the country’s National Bureau of Statistics, China’s population has declined substantially in each of the past three years: by 850,000 in 2022, 2.08 million in 2023 and 1.39 million in 2024.

The plunge enabled India to overtake China as the world’s most populous country, and at the start of 2025, China’s population stood at 1.4 billion.

Despite state subsidies and incentives, only fleeting improvements have been observed.

China now risks growing old before it grows rich, with major implications for the whole of society and especially the economy.

Historically, China has always had a huge population. Under Mao Zedong, the Communist Party rejected family planning and pursued rapid population growth as a source of national strength.

From 1949 to 1976, the population nearly doubled, reaching 940 million from 540 million.

However, following the Cultural Revolution and during Mao’s final years in the early to mid-1970s, Chinese leaders became concerned about the nation’s ability to sustain its expanding population.

Population control measures were introduced.

The first such initiative, dubbed “later, longer, fewer,” raised the legal age of marriage to 23 for women and 25 for men, encouraged a minimum three-year gap between births and limited families to two children.

The government set up birth planning offices, working alongside local authorities to penalize noncompliance.

The campaign, which became more stringent over time, sharply reduced fertility: from 6.1 children per woman in 1970 to 2.7 in 1980.

It was followed in 1980 by the infamous one-child policy, which limited urban couples to one child and led to many forced abortions and sterilizations.

Although initially intended to be temporary, the policy was not relaxed until 2015, when couples were allowed to have two children.

All restrictions have since been lifted, but the long-term damage has been difficult to undo.

By 2050, a third of the population will be over the age of 60, up from 12 percent in 2010, making it the oldest population in the world.

This demographic shift will strain welfare systems, shrink the workforce, weaken domestic demand and economic growth, and worsen regional inequality.

China’s working-age population is already contracting.

In 2023, there were 857.98 million people aged 15 to 59 – down 77 million from 2013.

What’s more, younger workers are concentrated in wealthy coastal cities and provinces such as Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjin and Guangdong, while central and western provinces such as Sichuan, Hunan and Heilongjiang struggle with youth outmigration and falling birthrates.

This trend is likely to exacerbate long-term inequalities between coastal and inland provinces.

Interior regions face labor shortages and declining productivity – both of which are historical precursors to unrest.

Another legacy of the one-child policy is the gender imbalance.

Due to widespread sex-selective abortions favoring male offspring, there is now a surplus of around 35 million men.

This imbalance is particularly acute in less developed rural areas.

As a result, many rural men struggle to find a partner; projections suggest that by 2027, one in six young Chinese men will be unable to marry.

Some are looking abroad, to countries such as Russia, Vietnam and Cambodia, but “importing brides” remains controversial and too uncommon to have a significant effect.

Too Little Too Late

The government has tried to reverse the decline.

Localities now offer birth incentives and housing subsidies.

For instance, Hohhot, the capital of Inner Mongolia, pays 10,000 yuan ($1,400) for a first child, 50,000 yuan for a second and 100,000 yuan for a third.

In the poorest regions, such as Inner Mongolia or Tibet, such incentives may bear fruit, but they do not address regional labor imbalances.

Young people will continue to seek employment in wealthier regions, leaving behind aging populations.

Moreover, birth incentives are unlikely to succeed in affluent areas, where values have changed: women have more career opportunities, and young parents often prefer to have fewer children and invest more in their education.

So far, the central government has ignored deeper structural problems, including gender inequality in pay and opportunity (though recent steps such as equal pay and extended maternity leave are promising), high living costs and the pervasive uncertainty faced by younger generations amid the trade war with the U.S. and the lagging domestic economy.

Despite a slight uptick in births in 2024 – attributed to the auspicious Year of the Dragon – the population continues to age rapidly.

Roughly 22 percent of the population – more than 310 million people – is 60 or older.

By 2035, this figure could exceed 30 percent.

In addition to labor shortages and regional disparities, rising health care and pension costs as the population ages will hinder economic growth and complicate the shift to a consumption-driven model.

Another limiting factor is the spending behavior of different cohorts.

The elderly tend to spend less and invest conservatively.

But amid high living costs, stagnant wages, job insecurity and a weak social safety net, younger working-class urban residents are also preferring to save.

Even among the educated youth, saving is now more common due to high unemployment, limited job prospects and the overall bleak economic outlook.

The one-child policy also entrenched the “4-2-1” family structure, in which one young adult supports two parents and four grandparents – which forces financial conservatism.

Since the founding of the People’s Republic, Chinese leaders have often prioritized surface-level fixes over structural reforms.

The current trends are unlikely to improve significantly in the short term, making a full transition to a consumption-based economy untenable for now.

Nevertheless, the current export- and investment-driven model is also no longer viable, given diminishing returns on infrastructure and real estate, extremely high local government debt and market saturation.

Of all possible reforms, boosting consumption remains the most feasible path to economic recovery.

However, demographic decline and population aging severely constrain this effort, while also weighing heavily on overall growth.

Structural reforms to improve income distribution and social safety nets could gradually raise consumption, but reversing population decline is not achievable in the short run.

Given the deep interconnection between these two challenges, the road ahead for China’s leadership will be arduous.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario