Sticks and carats

The biggest bugs in the new gold rush are Asian

Wall Street is loading up on bullion. So are people in China and India

Gold was already on a tear when President Donald Trump unveiled sweeping tariffs on much of the world earlier this month, briefly sending the price of the metal to an all-time high of $3,166 per troy ounce, up 17.4% from the day of his inauguration.

On April 11th it surged past $3,200.

In one part of the world, however, that has hardly curbed consumers’ enthusiasm.

“Rising gold prices stopping your wedding jewellery purchase?” asks a sign outside the downtown Mumbai branch of Tanishq, India’s biggest jewellery retailer.

“Pay nothing for your dream,” it declares, advertising a “festival of exchange” to trade in old jewellery for new.

Even as the gold price surged through 2024, demand in India stayed steady.

Absolute price levels don’t really matter, says Anindya Banerjee of Kotak Securities, a broker.

What matters is that there are no sharp falls. According to the World Gold Council, a trade association, Indians are still buying “need-based” gold jewellery, such as for weddings and other occasions.

They are taking up offers like Tanishq’s to update old jewellery for new designs.

Loans against gold are soaring, too.

Asian countries are voracious consumers of the yellow metal.

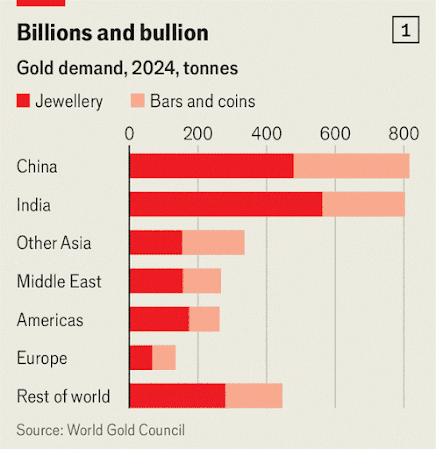

Last year India was the world’s biggest buyer of gold jewellery, its combined purchases of 560 tonnes outpacing even China’s 510 tonnes (see chart 1).

Indians also bought 240 tonnes of gold bars and coins, and Chinese purchased a whopping 345 tonnes.

In Thailand, demand for bullion jumped 17% in 2024 to 40 tonnes, owing to the growing popularity of apps that sell physical gold online.

Add in other markets, such as Indonesia and Vietnam, and Asia accounted for 64.5% of global demand for gold jewellery and bullion last year, not including central-bank purchases, roughly in line with their share of global population but greater than average incomes would suggest.

Asia’s love of gold is partly to do with its role in important life events, especially weddings.

Kalyan Jewellers, a big retailer, estimates that “India is a market of approximately 10m marriages annually, and this market alone is estimated to cater to 300 to 400 tonnes of gold.”

Many Hindus also buy gold on auspicious days, such as during the season that culminates with Diwali in the autumn, or on Akshaya Tritiya, a spring festival which this year falls on April 30th.

Gold is deeply woven into Chinese cultural traditions, too.

It is purchased to celebrate weddings, a baby’s first-month anniversary and other milestones, both on the mainland and among the diaspora.

In previous generations it was one of the few ways to store wealth and hand it down to descendants.

And beyond the mainland, many diaspora Chinese groups have adopted the wedding tradition of the Teochew communities in South-East Asia.

The groom’s family buys four items of gold jewellery—usually a necklace, bangle, earrings and ring—for the bride, to symbolise the four corners of the roof that a husband is expected to provide.

Au contraire

As a result, Asians’ fondness for gold is often attributed to cultural reasons.

But India and China are culturally very dissimilar, and South-East Asian countries would chafe at being lumped in with either.

Underlying the cultural motives are deeper economic and financial ones that help explain gold’s enduring popularity.

A crucial one is diversification.

Investors across the world prize gold as a store of value and as a hedge against inflation, especially in turbulent times.

Indeed, Americans have been piling into gold since Mr Trump took office, snapping up more of the stuff early in March than at the height of the pandemic in 2020.

A gold broker in Singapore says he has been arranging bulk shipments for anxious rich people, who are hoarding the metal.

But in much of Asia it serves an additional role: as a currency hedge and a way to gain exposure to an asset not linked to the national economy.

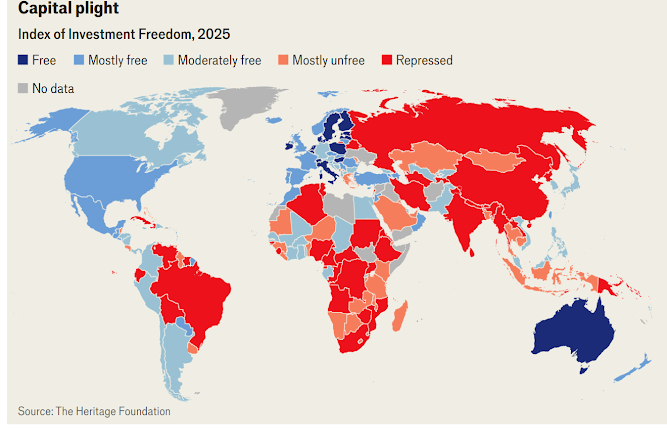

Asian countries, especially India and China, fare poorly on an index of investment freedom (see map).

Capital controls are common, and investing in foreign markets ranges from difficult to impossible.

“It’s the only way for our caged capital to easily buy non-rupee assets,” says Joseph Sebastian, an investor at Blume Ventures, a venture-capital firm in Mumbai.

Despite a recent investing boom, less than 6% of Indian household assets are allocated to equities, compared with 15% in gold.

In China, even domestic investment can be hard.

Many profitable industries are controlled by the government and remain off-limits to retail investors.

Chinese equity markets traded below their pandemic highs even before Mr Trump’s threat of tariffs caused market turmoil, and far below historic peaks.

Property has lost its sheen as a route to building wealth ever since a government crackdown on speculation and debt: prices for new homes are down 5% from their peak in 2021.

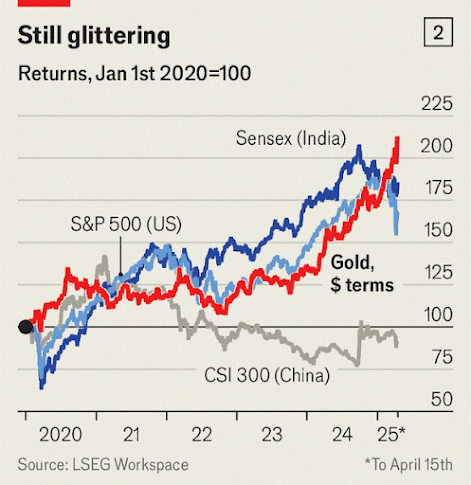

The benchmark gold price doubled to 737 yuan per gram in the five years to the end of March, an annual return of 15.4% (see chart 2).

For mainland Chinese gold has become more attractive as China’s economy has slowed. Rather than keeping their cash in a bank that may generate interest of 1-2% each year, young Chinese prefer to buy small amounts of gold—as little as a one-gram “bean”. Government policy also fuels interest. “When China’s central bank buys gold, people think ‘Oh, I should buy gold as well’,” says Alex He, a gold trader in Xi’an. There has been a shift away from jewellery to bullion, suggesting that purchases are driven by investment.

No less important is gold’s role in ensuring financial stability.

In China, India, Pakistan and most of South-East Asia, less than half of people of working age are enrolled in a mandatory pension.

Gold serves as a safety-net for old age.

It is particularly important for women, who in many Asian countries lack the earning potential of men, and in some places, such as South Asia, often have no assets in their name.

Gold is also crucial to smooth out cashflows for farmers and traders, whose income is vulnerable to climatic and economic vagaries.

Like Chinese youth, many rural Indians put away small sums to buy gold to ensure access to liquidity when times are tight.

India’s weak system of land records and its underdeveloped mortgage market are obstacles to borrowing against land.

That has created a thriving and increasingly formal gold-loan market.

Muthoot, India’s largest gold-loan firm, issues loans in under 15 minutes and is seeing a greater number of middle-income borrowers.

Loans against gold grew 68% between April and December last year, up from 12.7% in the last nine months of 2023.

Economists complain that the colossal sums invested in gold could be allocated to more productive investments.

An even bigger complaint is the effect on the trade balance.

Last year Thailand’s central bank blamed high gold imports for transforming a current-account surplus into a deficit.

Gold accounts for 8% of India’s overall imports.

In some months it is the country’s single largest import category.

In the fiscal year ending March 2024, India’s $45bn in net gold imports was nearly twice its current-account deficit.

That puts downward pressure on the Indian rupee, further boosting demand for gold.

From a macro point of view gold is bad, says Mr Sebastian, “but from a micro personal point [of view], I still have 20% of my assets in gold.”

Gilt trip

There is no easy fix.

Governments could implement policies to discourage gold buying.

But that would just boost smugglers and black markets.

Another option is to source more production at home, though geology may have other ideas.

China is the world’s largest gold producer, at a hefty 378 tonnes in 2023, but even that accounted for just over 40% of demand for jewellery and bullion.

Indian production has been in decline for decades despite substantial ore resources, partly due to restrictive rules.

India produced just one tonne of gold in 2022, a year in which it imported over 700 tonnes.

Governments that want to decrease gold imports instead need to look at harder or unpalatable reforms, such as deepening credit markets, fixing land records, unclogging the judicial system or freeing up the movement of capital.

For all the cultural reasons so often bandied about, it is economics and politics which ensure that Asians remain gold bugs.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario