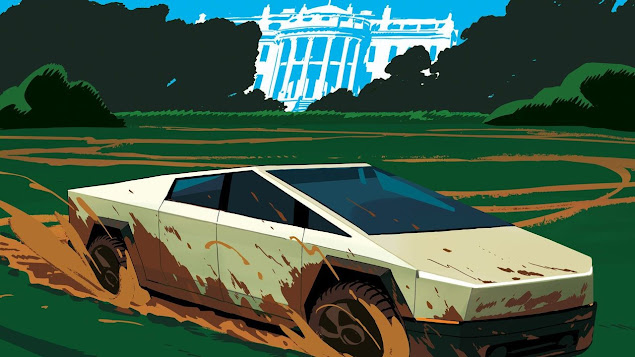

Cyber muck

Elon Musk is powersliding through the federal government

But to what end?

The United States Institute of Peace (usip) was established by Congress in 1984 to promote an end to conflict all over the world.

Forty years later it came to an end with an armed stand-off at its headquarters, a glass and acid-etched concrete building just off the National Mall.

usip is not part of the executive branch.

It is an “independent nonprofit corporation”, according to its founding law, and owns its own building.

Yet on February 19th Donald Trump issued an executive order to shut it down.

Its president, George Moose, resisted but could not hold out.

On the afternoon of March 17th Elon Musk’s “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE) came to visit.

The incursion was just one of dozens of raids conducted by DOGE on various parts of government.

The tension it sparked, and the nature of DOGE’s tactics, illustrate the extent to which Mr Musk has become Mr Trump’s enforcer.

According to an affidavit by Colin O’Brien, the Institute’s head of security, at around 2.30pm, three cars packed with men turned up at the headquarters.

They were let into the lobby by Kevin Simpson, an employee of Inter-Con, a contractor which had managed the building’s security until Mr O’Brien cancelled the contract.

Mr Simpson had nonetheless retained a physical key.

According to Mr O’Brien, Derrick Hanna, a vice-president at Inter-Con, said the firm had been threatened with losing all of its government contracts if it did not co-operate and let doge in.

usip’s lawyer then called the DC police department to report a break-in.

Mr O’Brien meanwhile electronically locked all of the building’s internal doors.

The stand-off was resolved when the police, apparently on the advice of Ed Martin, Mr Trump’s interim US attorney for the District of Columbia, forced Mr O’Brien and his colleagues to open up, before escorting them off the premises.

By the following day the institute’s website was offline and its signage had been removed from its headquarters.

The organisation’s 400-or-so staff, many of them working in conflict zones, are now in limbo.

In the past two months doge has ripped through the federal government.

It has already obliterated one whole department, USAID, America’s aid agency.

Within others it has unleashed chaos with sudden firings and equally sudden reversals under court orders.

Almost across the board, with its threatening emails, mass firings and its hoovering-up of sensitive government data, DOGE has provoked something close to panic among civil servants.

“They have created confusion, fear and loathing across the entire federal workforce,” says Max Stier of the Partnership for Public Service, a charity that works to improve government.

Is this a necessary part of a transition to more efficient government, or is something else going on?

There is little doubt that the government needs to change.

“Reform is absolutely needed on both a micro level and a macro level,” says Steve Goodrich, a consultant with decades of government experience.

Reports from the Government Accountability Office list failure after failure.

And Mr Musk’s record in the private sector is replete with success in cutting costs and getting seemingly impossible things done quickly.

Part of his mantra is that the only unbreakable rules are the laws of physics.

When DOGE was first mooted, few predicted it would so quickly shape Mr Trump’s second term.

After all, this would not be the first time a Republican president brought in a businessman to fix the government.

In 1982, Ronald Reagan also pledged to “drain the swamp”.

He launched the Grace Commission, led by Joseph Peter Grace, a chemicals industrialist.

Grace’s group promised to save $424bn of spending in three years, not much less relative to the economy than Mr Musk’s promise to cut $1trn in one year.

Most of its recommendations came to little.

Ludicrous speed

The planning for something far more dramatic under Mr Trump seems to have begun even before the election.

On a recent podcast, Senator Ted Cruz recalled a meeting with Mr Musk in September or October where the tech billionaire said he wanted “the login for every computer” at the government.

By the time Mr Trump took office on January 20th, there was a clear blueprint.

With an executive order, Mr Trump inserted DOGE into an existing organisation, the United States Digital Service (usds), and gave it a mandate to access any government IT system.

With this, Mr Musk’s new employees—almost all young, male software engineers—set to work.

They wear hoodies, carry multiple phones and suck on Zyn nicotine pouches.

Some have been sleeping at the offices of the General Services Administration.

To career civil servants they are known as the “Muskrats” or “the Bobs” (after consultant characters in “Office Space”, a cult film).

The youngest, Edward Coristine, nicknamed “Big Balls”, is just 19 years old and, according to Reuters, previously ran a firm that provided tech support to a cybercrime ring.

Mr Musk says that he doesn’t think “anything has been this transparent ever”, but DOGE has been secretive from the beginning.

Its workers hid their names at the agencies they arrived in.

For several weeks, government lawyers told judges that they did not know who the administrator formally in charge of DOGE was.

At the end of February they relented and named Amy Gleason, a former USDS employee, as acting administrator.

But in a sworn statement on March 19th, Ms Gleason admitted that nobody reports to her, and that DOGE still has no organisational chart.

DOGE appears to be run by Mr Musk directly and by his trusted lieutenants from business, such as Steve Davis, a longtime collaborator.

Mr Trump told Congress on March 4th that DOGE is “headed by Elon Musk”.

Mr Musk seems to have almost completely ditched his other jobs, and has been sleeping at the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, next door to the White House.

He has an office there where he has apparently installed a gaming computer with a large curved monitor.

The extent of Mr Musk’s ambition became clear a week after the inauguration, when almost all federal workers received an email offering “deferred resignation”.

It was entitled a “fork in the road”, the phrase Mr Musk used when he took over Twitter in 2022.

Since then tens of thousands of “probationary” government workers have been fired, only to be reinstated after judges ruled that the Office of Personnel Management (opm), the federal government’s HR department, had exceeded its authority.

Many of them are now back.

DOGE’s work has gone far beyond trimming headcounts, though.

Its workers have also grabbed government data.

In February, when USAID was, in Mr Musk’s words, fed “into the woodchipper”, DOGE recruits were trying to take control of the Treasury’s central payment system to stop its payments out to contractors.

In the weeks since, they have tried, with varying degrees of success, to get access to data from the Internal Revenue Service, from the Social Security Administration and from the Department of Labour, among other places.

On March 20th Mr Trump signed an executive order strengthening their ability to do this, though court fights continue.

Some of the efficiency drive has been beyond parody.

After one early mass firing of probationary workers at the National Nuclear Security Administration, which manages America’s nuclear weapons, the agency was forced to issue an agency-wide memo to get contact details with which to beg them to come back.

The DOGE workers who did the firing had apparently not thought to ask for personal email addresses before cutting off government ones.

In another mess, the names of recently recruited CIA agents were sent in an unclassified email to the opm after DOGE’s request for the details of all probationary employees.

Their names may now be known not just to DOGE, but to China’s government too.

What does this add up to?

Mr Musk is not yet cutting the budget deficit much.

Civil servants’ wages make up only around 5% of federal spending.

Firing irs agents in particular could cost a fortune in uncollected taxes.

Other cuts have hit scientific research and software licences.

Some of this no doubt needed trimming, but the cuts have been indiscriminate.

Super heavy

As for efficiency, it is hard to see much of it.

“I’ve done nothing but put out doge fires for six weeks,” says one government lawyer.

Veterans Affairs psychiatrists now deliver therapy in busy open-plan offices because they can no longer work from home.

Park rangers have to beg to be allowed to buy petrol.

An inbox to which workers have been ordered to send weekly bulletin-point diaries is full.

Workers are furious.

One employee at the Treasury who voted for Mr Trump three times describes Mr Musk as “the literal antiChrist”.

There are enormous conflicts of interest here, notes Don Moynihan of the Ford School of Public Policy in Michigan.

After all, Mr Musk’s companies have faced probes from almost every federal regulator the billionaire is now gutting.

Yet Professor Moynihan goes on to say that grift does not explain DOGE.

Even with Mr Trump filming a free Tesla advert on the White House lawn; the commerce secretary tipping its stock on live TV; and people who vandalise Teslas threatened with deportation to El Salvador, Tesla’s market value has slumped.

In his interview with Mr Cruz, the Tesla boss described his work as “reprogramming the Matrix”.

He laid out a conspiracy theory in which vast sums of government money are sent by “magic money machines” to left-wing charities whose leaders “buy jets and homes and… live like kings and queens”.

What remains is used to bribe foreigners to move to the United States.

“By using entitlement fraud, the Democrats have been able to attract and retain vast numbers of illegal immigrants and buy voters,” he said.

Some 20m people have supposedly been spread across swing states to rig elections.

The obvious problem with this is that it is nonsense.

To take one example, the $1.9bn Mr Musk says was sent personally to Stacey Abrams, a Democratic politician in Georgia, was spent on renewable-energy projects.

Insane mode

Grover Norquist, a conservative activist, once famously said he wanted to cut the state “to the size where I can drag it into the bathroom and drown it in the bathtub”.

Half a dozen federal workers interviewed by The Economist have cited that same quote to explain what they think Mr Musk is doing.

He has, for example, taken an axe to the Social Security Administration—ordering dozens of its physical offices to be closed and threatening to get rid of its phone helplines.

This is unlikely to stop much fraud, but it may mean that fewer people who are entitled to benefits claim them.

Some think that the ultimate plan is to replace most workers with an AI and that this explains why DOGE is grabbing so much sensitive data.

One thing that is certain is that Mr Musk is centralising power to get things done that might otherwise be blocked by Congress or the courts.

DOGE’s demolition of USAID achieved a longstanding goal of Mr Trump’s to reduce money sent to foreign countries, and though a court has now ruled it was probably unconstitutional, it will be hard to rebuild the agency.

Courts are simply not set up to reverse these sorts of scorched-earth tactics, argues Anna Bower of Lawfare, a specialist legal-news site.

Similarly, cutting off grants to universities may damage things like cancer research, but by putting that power directly in the hands of the president, Mr Musk has helped Mr Trump to impose his will on institutions like Columbia University.

The power to make sudden cuts gives Mr Trump enormous leverage.

Republican congressmen, who are meant to hold the power of the purse, now have to ring up Mr Musk and ask for cuts in their districts to be reversed.

In a tweet posted on March 7th Tom Cole, a representative from Oklahoma, announced that he was “thrilled to announce that common sense has prevailed” after he worked with DOGE to reverse office closures planned for his district.

Two days before, Mr Musk met with Republican members of Congress and handed out his mobile phone number.

The possibility of targeted cuts is something Republican congressmen must consider before expressing disloyal thoughts.

What this adds up to is an upending of America’s constitutional order of a sort unseen since Nixon’s presidency, if not before.

It may yet burn out.

Mr Musk has already begun to clash with cabinet members, some of whom do not like having their authority usurped.

Polling suggests the billionaire is far less popular than his boss.

The takeover of USIP aside, there are some signs of tactical retreat.

Most cuts now at least are nominally “advised” by DOGE, rather than directly ordered.

The pressure on the group will only grow in coming months, says Ms Bower, as litigation ties the government up in knots and discovery reveals more of what DOGE is up to.

All of this might doom the work of lesser men.

But with his businesses, Mr Musk has defied gloomsters.

If his project in government succeeds, he could get a lot done.

Whether that would be good for America is another thing.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario