Trump and the end of American soft power

Joseph Nye coined the term for the influence countries exert through attraction. Here he sets out why exclusive nationalism is likely to prove a losing strategy

Joseph S Nye

International relations is power politics.

As Thucydides wrote more than two millennia ago, the strong do as they will and the weak suffer what they must.

Power, however, rests on more than bombs, bullets and economic coercion.

Power is the ability to affect others to get the outcomes one wants, and that can be done through attraction as well as through force and payment.

Because this attraction — soft power — is rarely sufficient by itself, leaders can find hard power more tempting.

But in the longer term, soft power often prevails.

The Roman empire rested not only on its legions, but also on the attraction of Roman culture.

The Berlin Wall came down not under an artillery barrage, but from hammers and bulldozers wielded by people who had lost faith in communism and were drawn to the values of the west.

A nation’s soft power rests upon its culture, its values and its policies when they are seen as legitimate by others.

That legitimacy is affected by whether a nation’s actions are perceived as congruent with or contradicting widely held values.

In other words, attention to values enhances a nation’s soft power.

A smart realist provides room for including some widely shared values in the definition of the national interest.

There is an important difference between inclusive and exclusive nationalism.

“America First” is a great slogan for American elections, but it attracts few votes overseas.

President Donald Trump does not understand soft power.

His background in New York real estate gave him a truncated view of power limited to coercion and transactions.

How else can one explain his bullying of Denmark over Greenland, his threats to Panama, which outrage Latin America, or his siding with Vladimir Putin over Ukraine, which weakens seven decades of the Nato alliance — not to mention his dismantlement of the US Agency for International Development (USAID) that John F Kennedy created?

All undercut American soft power.

Writing after the English civil war in the mid-17th century, Thomas Hobbes imagined a state of nature without government as a war of all against all, where life was “nasty, brutish and short”.

In contrast, writing in a somewhat more peaceful period a few decades later, John Locke imagined a state of nature as involving social contracts that permitted the successful pursuit of life, liberty and property.

Locke’s ideas became enshrined in American political culture.

Liberals in the Lockean tradition argue that although there is no world government, there are many social contracts that provide a degree of world order.

After victory in the second world war, the US was by far the most powerful nation, and it attempted to enshrine these values in what became known as “the liberal international order” upheld by the UN, the Bretton Woods economic institutions and others.

The US did not always live up to its liberal values, but the postwar order would have looked very different if the Axis powers had won.

These institutions served the US national interest.

But liberal values and institutions mean little to Trump, and he has weakened or withdrawn from several.

One of the most important norms of the UN system is that states are not supposed to take their neighbours’ territory by force.

It is a norm that Russia blatantly violated with its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.

Yet on the third anniversary of the war, Trump refused to condemn Russia’s violation and the US instead voted with Russia in the UN.

The rise of human rights law after the second world war, including the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, was a reaction to the horror of genocide.

While many nations have signed up to these conventions, they often fail to adhere to them, or they interpret them in different ways.

The world is far from a consensus on liberal values — and even within democracies, the rise of populist nationalism shows deep differences.

Nonetheless, universal values affect politics and power.

Trump’s myopic transactionalism misses this “truth social”.

Values affect a nation’s attractiveness or soft power, and surveys show that the most admired countries have tended to be liberal democracies.

The US has generally ranked near the top. Autocracies such as Russia or China tend to rank lower.

On the other hand, attractiveness depends on the perceptions of the beholder and can vary from country to country and group to group within countries.

Autocracies sometimes find other autocracies attractive.

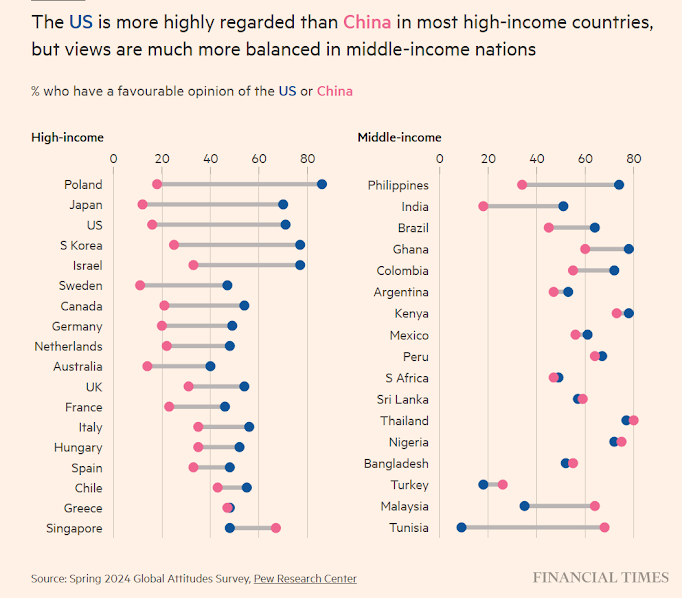

It is interesting that in the great power competition between the US and China, recent Pew polls find China lagging behind the US on most continents, but the two countries are roughly tied in Africa.

The case of China is particularly interesting regarding soft power and universal values.

As China dramatically developed its hard power resources, leaders realised that it would be more acceptable if it were accompanied by soft power.

This is a smart power strategy because as China’s hard military and economic power grew, that could frighten its neighbours into balancing coalitions.

If it could accompany its rise with an increase in its soft power, China could weaken the incentives for these coalitions.

In 2007, then Chinese President Hu Jintao told the 17th Congress of the Chinese Communist party that they needed to invest more in soft power, and this continued under President Xi Jinping.

Billions of dollars were invested in Confucius Institutes and foreign aid programmes — but China has had mixed success with its soft-power strategy.

Its impressive record of economic growth, which has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, and its traditional culture have been important sources of attraction, but polls show it lags behind the US, including in Asia.

These numbers may change as China steps into the gap that Trump is creating.

Much of a country’s soft power, however, comes from its civil society rather than from its government.

Government propaganda is usually not credible and often does not attract and thus does not produce soft power.

China needs to give more leeway to the talents of its civil society, but this is difficult to reconcile with tight party control.

Chinese soft power is also held back by its territorial disputes with its neighbours.

Creating a Confucius Institute to teach Chinese culture will not generate positive attraction if Chinese naval vessels are chasing fishing boats out of disputed waters in the South China Sea.

And assertive “wolf warrior diplomacy” responds to popular nationalism at home, but is counter-productive abroad.

It can undercut the soft power benefits from infrastructure spending in China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

It is interesting that unlike during the cold war days of Mao Zedong, China’s soft power strategy has rested less on ideological proselytising of universal communist values and more heavily on transactional relationships.

In contrast, though American soft power also rests in part on transactions, it has relied heavily on values related to democracy and liberal views of human rights.

Some Europeans described cold war Europe as divided into two empires — but the US presence in western Europe during the cold war was an “empire by invitation” in contrast to the Soviet empire in eastern Europe.

However, with Trump’s recent bullying of Volodymyr Zelenskyy and his false statements about Ukraine — combined with the critical speech given by vice-president JD Vance at last month’s Munich Security Conference — Europeans and others have cause to worry about the US commitment to Nato as an alliance of democracies.

In Trump’s view, the post-1945 world order of rules, institutions and alliances has suckered the US into accepting unfair trade practices and paying for foreign defence.

He describes himself as a dealmaker (“My whole life is deals”) and sees the US-led world order as a bad deal.

But he is so obsessed with the problem of free riders that he forgets that it has been in America’s interest to drive the bus.

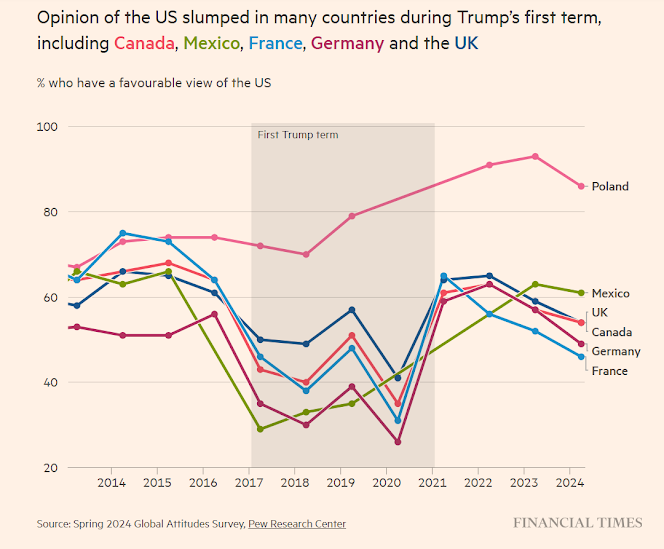

The years of Trump’s first term were not kind to US soft power.

This was partly a reaction to his narrowly nativist foreign policies of turning away from allies and multilateral institutions, summarised in his slogan “America First”.

Friends became even more concerned when Trump undercut universal values of democracy by trying to disrupt the orderly transition of political power after he lost the 2020 election.

January 6 2021 witnessed the shock of a mob invading the Capitol building in Washington.

Polls show that American attractiveness diminished during Trump’s first term.

It recovered somewhat under the presidency of Joe Biden, with his rhetoric about democracy, and revival of support for multilateral institutions and alliances.

But the history of Trump’s first term leads one to expect a decline in his second.

In a longer historical perspective, American soft power has suffered decline before, particularly after the wars in Vietnam and Iraq.

However, the US has demonstrated a capacity for resilience and reform.

In the 1960s, cities were burning over racial protests and the streets filled with anti-war protesters.

Bombs exploded in universities and government buildings.

Martin Luther King and two Kennedys were assassinated.

Yet within a decade, a series of reforms passed Congress, and the honesty of Gerald Ford, the human rights policies of Jimmy Carter and the optimism of Ronald Reagan helped restore American soft power.

Moreover, even when crowds marched through the world’s streets protesting against US policies in Vietnam, the protesters sang Martin Luther King’s “We Shall Overcome” more than the Communist Internationale.

An anthem from the American civil rights protest movement based on universal values illustrated that America’s power to attract rested not on government policy but in large part on civil society and a capacity to be self-critical and reform.

Many soft-power resources are separate from government — such as Hollywood movies, a diverse, free press and freedom of inquiry at universities

Unlike hard-power assets (such as a nation’s armed forces), many soft-power resources are separate from the government and attract others despite politics.

Hollywood movies that showcase independent women or protesting minorities can attract others.

So too does a diverse and free press, as well as the charitable work of US foundations and the freedom of inquiry at American universities.

Companies, universities, foundations, churches and protest movements develop soft power of their own, which may reinforce others’ views of the country.

Peaceful protests can actually generate soft power.

By contrast, the Trump-inspired mob in the Capitol in January 2021 was far from peaceful.

It also provided a disturbing illustration of the way Trump exacerbated political polarisation by making his myth of a stolen election a litmus test in the Republican party.

The US has become increasingly polarised during the past two decades, a shift that was under way well before the 2016 election.

Many senators and Congress members were cowed by threats of a primary challenge by members of Trump’s base.

As Trump, with the help of billionaire Elon Musk, weakens democratic norms, destroys institutions and asserts the power of what his supporters call the “unitary executive” presidency, some critics fear that January 2021 was a harbinger of democratic decline.

Trump’s blanket pardon of violent protesters has reinforced these fears.

If these trends continue, they will weaken American soft power.

A man in Jordan carries a package from USAID in 2003 © Reuters

Fortunately, there are reasons not to write off American democracy just yet.

Courts work slowly, but they still work.

If Trump’s economic policies lead to inflation or painful reductions in social programmes, he will probably lose the House of Representatives in 2026, which would restore some checks and balances.

Markets can also produce constraints.

And in a federal system, there are multiple centres of power.

In 2020’s election a democratic political culture produced many local heroes, such as secretaries and state legislators who stood up to Trump’s efforts to intimidate them into “finding” votes.

And that election result was upheld in more than 60 court cases overseen by an independent judiciary.

This does not mean that all is well with American democracy.

The first Trump presidency eroded a number of democratic norms, and the pace has increased since his second inauguration.

Social media models, some controlled by Trump and Musk, are based on algorithms that profit from polarising extremism, and artificial intelligence makes all social media subject to manipulation by conspiracy theorists.

The problem of polarisation is far from solved, and there is much to worry about in democratic terms.

Soft power is only part of a country’s power.

It must be combined with hard power in ways that are mutually reinforcing rather than contradictory. And democratic values are not the only source of soft power.

A reputation for being benevolent and competent also generates attraction.

But legitimacy matters, and for much of the world where democracy and rights are important, a country’s alignment with those values is a vital source of soft power.

True realism does not neglect liberal values or soft power.

But extreme narcissists such as Trump are not true realists, and American soft power will have a hard time during the next four years.

Joseph Nye is former dean of the Kennedy School at Harvard University and author of the recent memoir ‘A Life in the American Century’

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario