Credit bubble hiding in plain sight

Unaware of the credit bubble? I bet you are aware of the debt bubble — but debt equals credit. The debt bubble is the credit bubble

ALASDAIR MACLEOD

Particularly since the end of Bretton Woods, the quantity of government and other debt has risen inexorably.

We are all aware of that, of soaring government debt to GDP ratios and unproductive private sector debt.

After the Lehman Crisis, there was a general view that debt was the problem.

Global debt at that time was estimated to be about $210 trillion, and it was commonly thought that it would have to stop growing and be paid down.

Today it is estimated by the Institute of International Finance to be $318 trillion.[i]

But this is not the whole story.

In its recent paper, the IIF doesn’t define debt. Its definition appears to comprise government, financials, non-financials and consumers.

Let’s call that the obvious debt, because excluded is an immense mountain of derivatives and foreign exchange obligations.

An obligation may have a market value worth a fraction of the principal.

Nonetheless, the obligation remains a debt until it is extinguished.

According to the BIS, notional principal OTCs stand at over $700 trillion.

We should strip out interest rate swaps, because they don’t involve principal amounts, only material balances whose gross market value is only $3.4 trillion.

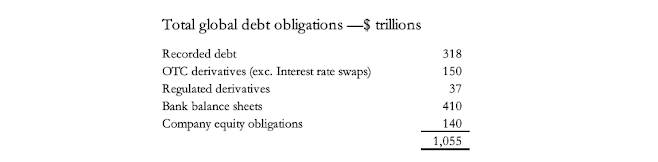

That leaves $150 trillion where there is an obligation (i.e. debt) on the principal, as shown in Chart B below.

In addition, there are regulated derivatives such as futures totalling a further $37 trillion.

Furthermore, there are options, which for simplicity’s sake we shall ignore.

Then there is the $410 trillion of bank balances, assets on one side and obligations to depositors, lenders, and shareholders on the other.[ii]

Taking it all together, a base of $318 trillion now becomes $915 trillion.

In the light of these enormous figures, bank notes and coin are insignificant.

So far, so good.

We are still missing out all sorts of other forms of debt described as non-debt, such as the obligations of companies’ managers to deliver income streams to their shareholders

That adds a further $140 trillion.

This yields the following:

In round terms, the debt bubble is over $1,000 trillion, excluding shadow banks which are not so much creators, but rather users of existing bank debt.

The reason for totting up debt obligations and obligations that may become recordable debt is that it is the counterparty to credit.

Therefore, the debt bubble is the same as the credit bubble.

And the credit bubble has generally been accumulating since the financialisation of western economies in the wake of London’s big bang.

Before the Second World War, credit bubbles corrected themselves by total credit contracting.

Broadly, the only way a system-wide credit contraction occurs is through defaults either at corporate or banking levels.

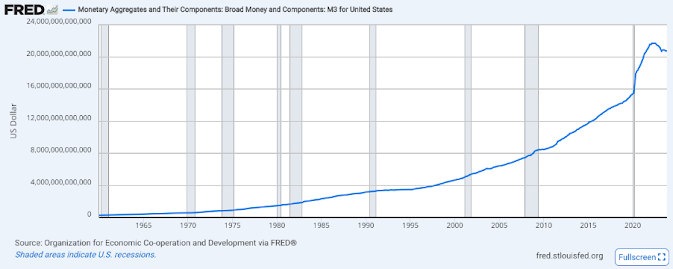

This is why US money supply, which actually measures credit, collapsed in the 1930s as thousands of banks went bust on the back of bad debts.

Otherwise, credit obligations get passed on into new hands.

Consequently, measures of money supply have continued to rise, as shown in the St Louis Fed’s chart of US M3.

The reason it has declined recently is not that credit has been destroyed, but it has been passed out of public circulation onto the Fed’s balance sheet through quantitative tightening, putting an alternative non-M3 debt in the form of government bonds into public ownership.

Otherwise, through nine official recessions (the shaded areas in the chart) credit has not contracted cyclically as it would have before the Second World War.

Credit which would have been destroyed through bankruptcy and bank failures has fed into subsequent expansions as accumulating malinvestments.

Instead of contracting numerically, credit contracts in value, as it has always done other than credit which is credible gold substitutes.

There are losses in individual classes of credit, such as a bear market in equities.

At the same time, increasing budget deficits due to a slump in global economic activity leads to an increase in the quantity of both government and corporate debt relative to nominal GDP, undermining their values.

A credit bubble popping undermines wealth, which it does at more than one level at the same time.

For example, the stock market crashes, and bond yields rise.

Those forms of credit lose value.

And the currency declines in value as well.

So hapless savers unaware of the fact that they are invested entirely in credit lose out twice over.

The refuge from this folly is to ditch credit in favour of real money.

That is why gold measured in credit (i.e. currency) appears to be rising, when it is in fact the currency declining.

The last to understand it are those who are ignorant of the difference between the two.

_____________________________________

[i] https://www.iif.com/portals/0/Files/content/Global%20Debt%20Monitor_May2024_vf.pdf

[ii] https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/financial-services/our-insights/global-banking-annual-review

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario