Old friends, new plans

India’s Faustian pact with Russia is strengthening

The gamble behind $17bn of fresh deals with the Kremlin on oil and arms

EVER SINCE the start of the war in Ukraine, the West has tried to persuade India to distance itself from Russia.

India has consistently rebuffed the entreaties.

Its officials have pointed out—in often testy exchanges—that the Kremlin has been a stalwart friend for decades.

Russia also accounts for about 65% of India’s arms imports over the past 20-odd years.

Besides, they argued, India needs to nurture the relationship to offset warming ties between Russia and China, India’s chief rival.

Western officials and observers concluded that this dynamic would change over time as India increasingly relied on America and its allies for commercial and military partnerships.

Their governments decided to strengthen economic ties and provide more advanced defence technology rather than hectoring India.

Thus followed deals such as one with America in 2023 to jointly manufacture fighter-jet engines on Indian soil.

India, however, sees its future with Russia very differently, as recent developments make amply clear.

First came news that Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, would visit India in early 2025.

A few days later, on December 8th, India’s defence minister, Rajnath Singh, arrived in Moscow to discuss new defence deals, including the purchase of a $4bn radar system.

That was followed by the two countries’ biggest-ever energy agreement, worth roughly $13bn a year.

Rosneft, Russia’s state oil company, is to supply some 500,000 barrels per day of crude oil to Reliance, a private Indian refiner, for ten years.

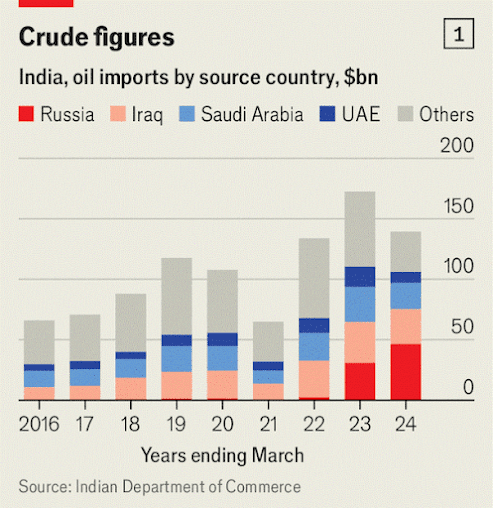

India has for the past few years cheerfully bought Russian oil for less than the $60-per-barrel price cap imposed by Western sanctions, becoming the world’s second-biggest buyer of the stuff after Chinan (see chart 1).

In 2021 just 2% of India’s oil imports came from Russia. Between April and October 2024 nearly 40% did.

ICRA, a rating agency, estimates that discounted Russian oil has saved India at least $13bn since the war in Ukraine began.

Rather than winding down an old cold-war friendship, as Western officials hoped, India is deepening defence, energy and other ties with a partner it sees as a source of prosperity and security and as a linchpin of its “multi-aligned” foreign policy.

And it is hoping that this will become less controversial with the return to the White House of Donald Trump.

The president-elect was friendly with India during his first term.

His pledges to bring peace to Ukraine through negotiation with Russia, if he follows through and meets with success, could also help ease pressure on Russia—and thus India.

This bet could pay off.

But the risks are severe.

That was demonstrated on January 10th when America escalated sanctions on Russian oil.

New measures target producers, insurers and traders, as well as the “dark” fleet of tankers that often carries Russian shipments. India (and China) could be forced to buy pricier oil from the Middle East.

Indian state refiners are now scrambling to speed payments for Russian crude and to secure delivery of 4.4m barrels currently at sea within a 48-day “wind-down” period allowed by American authorities, according to Bloomberg.

Mr Trump may ease the sanctions but that could take time, to preserve leverage in peace talks with Russia. If talks fail, the war could drag on.

And even if they succeed, and sanctions are lifted, the new oil deal is likely to add to India’s substantial trade deficit with Russia (see chart 2).

Turn next to defence. India has indeed become less reliant on Russian arms, buying from France, Israel and others.

Yet the prime minister, Narendra Modi, continues to cut deals with Russia.

In July 2024, just before Mr Modi visited Moscow, a Russian state arms manufacturer announced that it would make tank rounds in India.

Mr Modi and Mr Putin then agreed to pursue joint weapons development and manufacture.

Russian and Indian firms already jointly produce weapons in India, including tanks, fighter jets and missiles.

Mr Singh, the Indian defence minister, added substance on his own Moscow visit by discussing the purchase of Russia’s Voronezh radar system.

It can identify and track a range of threats, including ballistic missiles and aircraft, over distances of up to 8,000km (5,000 miles).

That would greatly enhance India’s capabilities, giving it coverage far into China, a range accessible only to a few powers.

Perhaps as important for India, some 60% of its components would reportedly be made in the country.

All of which suggests that India continues to view Russia as its primary source of top-end weaponry, much of which America and its allies remain reluctant to share.

And that Mr Modi sees Russia, alongside any willing Western partners, as a means to strengthen India’s defence industry.

Yet here too India faces risks.

Its defence co-operation with Russia has been plagued by problems, including the delayed delivery of the last two of five S-400 missile systems that it bought in 2018.

Poor performance of some Russian weaponry in Ukraine has caused concern among Indian military leaders.

And India has postponed or cancelled talks on several deals to buy or upgrade Russian equipment, citing logistical issues arising from the Ukraine war.

Mr Putin’s India trip, meanwhile, has been presented as a routine exercise following the two leaders’ vow to meet annually.

Still, it would be his first trip to India since his full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

And it could provoke the sort of PR disaster that marred Mr Modi’s Moscow visit, when he bear-hugged Mr Putin shortly after a deadly Russian missile strike on Ukrainian sites including a children’s hospital.

Even without another such atrocity, the visit is likely to undermine Mr Modi’s efforts to present India as a neutral party in the war.

For Indian officials the risks of strengthening ties with Russia appear to be acceptable.

But they may be underestimating a longer-term problem.

Russia is a useful short-term source of energy and technology.

But its demographic and economic prospects are grim, even were peace to return.

India is also exposing itself to fallout from Russia’s inevitable domestic turmoil—Mr Putin cannot live for ever—to say nothing of further Kremlin misadventures abroad.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario