Investing in Sports Has Arrived. Here’s the State of Play.

A fluid and disparate sports business ecosystem is being etched by a handful of pioneering private-equity firms.

By Andy Serwer

Gradually and then suddenly, the wily ways of Wall Street have come to the wide world of sports.

And while you’d think testosterone-driven financiers would be naturally drawn to sports, investments by the former in the latter had been rather limited heretofore.

Now, as these worlds increasingly collide, dealmaking is picking up and becoming more sophisticated.

First, at the headline level, private-equity executives have become go-to buyers of marquee sports teams.

Look no further than the latest megadeals: David Rubenstein, co-founder and co-chairman of The Carlyle Group, purchased the Baltimore Orioles for $1.725 billion in March, and Josh Harris, co-founder of Apollo Group Management, bought the Washington Commanders for $6 billion in July.

Second, investment firms themselves are acquiring stakes in, or entire teams, leagues, and global competitions—from women’s soccer and professional bull riding to lacrosse and sailing.

Third and most significantly for now, professional investors are snapping up and creating tertiary sports businesses, leveraging, say, broadcast, digital, and scripted series rights, as well as bespoke stadium concessions.

Example: George Pyne’s sports-focused investment firm Bruin Capital just bought a majority stake in a stadium grass-turf company.

It’s a fluid, disparate ecosystem being etched by a handful of pioneering private-equity firms.

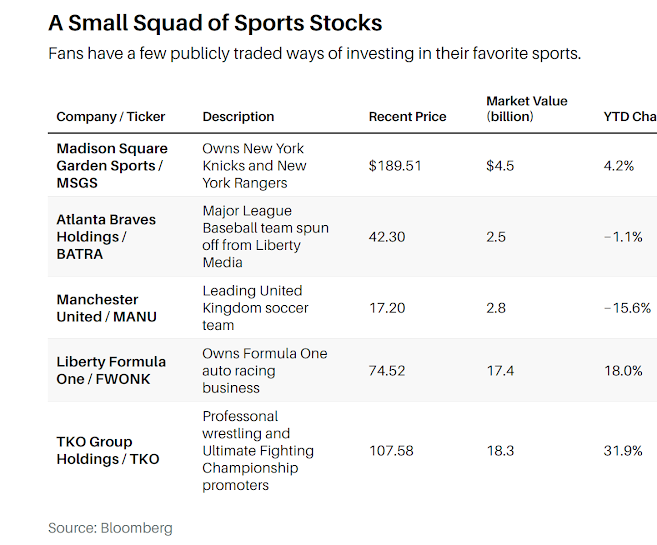

As such, there are very few publicly traded options for retail investors (see table below), but that will probably change soon as more investment firms enter the sports fray and ordinary Joes clamor to get their piece.

U.S. Invasion

The action is increasingly global.

In England, they are sounding the alarm, “The Americans are coming!”

Wealthy Yanks now control or own significant slices of half of Britain’s 20 Premier League teams (the nation’s top soccer conference), including a number with ties to investment firms.

Eldridge Industries CEO Todd Boehly owns Chelsea, a perennial contender from West London, while billionaire Wes Edens, co-founder of Fortress Investment Group, has a stake in Aston Villa from Birmingham.

Also, private-equity giant Silver Lake has a piece of powerhouse Manchester City.

Americans are picking up high-profile soccer teams in Italy and France, as well.

The influx of Wall Street money into sports is easy to figure.

Private-equity firms and their honchos—some unencumbered by shareholders and less beholden to regulators than their publicly traded brethren—have mountains of money.

To exclude them would effectively cap the valuations of sports properties.

Teams in newer leagues such as rugby or volleyball, or in women’s sports, covet that capital.

For example, in a recent $58 million deal, The Carlyle Group bought a majority stake in the Seattle Reign women’s soccer team.

Baseball, basketball, and hockey also crave the cash, and all of them—to one degree or another—now allow investment companies to buy into teams.

To date, the only holdout is the National Football League, and sure as a Patrick Mahomes’ second-half comeback, that day will come.

“We are making real progress on potential private equity,” NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell told reporters late last month at the conclusion of the spring league meeting in Nashville.

“We’re going to continue to be very deliberate, but I expect there to be something by the end of the year.”

In some instances, PE bankers are teaming up with star athletes, many of whom have generated significant coin themselves.

Former New York Giants quarterback Eli Manning, a partner at sports investment company Brand Velocity Group and who has an investment in women’s soccer team Gotham FC, recently expressed interest in buying into an NFL team.

Early Days

To be honest, though, this activity is mostly just scratching the surface.

Investment firms still can’t own U.S. teams outright, meaning the New York Yankees aren’t about to become a Blackstone portfolio company (although now that we’ve said it, wheels may start turning in Steve Schwarzman’s head).

Another critical, early-days caveat is that calling sports an asset class would be premature—despite some investors insisting it is one—at least according to Gerry Cardinale, founder, managing partner, and chief investment officer of RedBird Capital Partners, a sports, media, and financial-services investment company that manages $10 billion.

He describes a bit of a gold rush mentality among participants.

“If I brought any other industry to you and said I’m going to pay premium valuations for a minority stake with no governance, no information rights, and no pathway to liquidity, you would laugh me out of the room,” says Cardinale, formerly a Goldman Sachs partner who cut his teeth on sports deals going back three decades.

His concern hasn’t dampened enthusiasm by investment firms, though, which Cardinale sees as creating a disequilibrium.

“You’ve had this massive escalation in asset valuations because of money chasing deals, and none of the infrastructure in sports has really kept pace,” he says.

By infrastructure, Cardinale means everything from new, high-end stadiums rife with shopping, food, and amenities to cutting-edge digital media deals.

To Cardinale and his team, which includes Jeff Shell, who oversaw sports in his previous role as CEO of NBCUniversal, building out those frameworks spells an opportunity.

As such, RedBird has made investments where he says he can bring to bear his firm’s expertise.

For instance, RedBird just announced a new endeavor called Collegiate Athletic Solutions, which will invest in colleges and universities to “monetize a school’s intellectual property,” according to The Wall Street Journal.

(That could include creating and monetizing additional sports programming.

A template might be RedBird’s partnership through Skydance Media with the NFL for scripted and unscripted programming, resulting in a soon-to-be-released Netflix documentary on the Dallas Cowboys.)

RedBird has invested in the academy just as the National Collegiate Athletic Association signed a landmark $2.77 billion settlement and agreement to pay student athletes.

RedBird, which is looking to buy Paramount Global with Skydance—“We don’t have to do this deal; I think we’re really the only credible buyer,” Cardinale says—has also invested in Fenway Sports, which owns the Boston Red Sox and Britain’s high-profile Liverpool soccer team, and has deals with LeBron James and Nascar.

RedBird also has full ownership of Italy’s storied AC Milan soccer team (“a global fan base of 550 million”), the United Football League (along with Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson), and the YES Network, which is the nation’s biggest regional sports network, with local media rights of the New York Yankees, the Brooklyn Nets, soccer’s New York City FC, and the Women’s National Basketball Association’s New York Liberty.

Waxman’s Offense

Alan Waxman is CEO of Sixth Street, a private-equity investment firm with $75 billion under management that has gone deep into sports.

He is enamored with the possibility of turning sports properties into global consumer brands.

Another former Goldman hand, Waxman grew up in Austin, Texas, and theorized that his hometown and San Antonio were converging into a significant central Texas market.

In 2021, he put his money where his mouth was, buying a piece of the San Antonio Spurs with tech billionaire Michael Dell.

Thanks to digital media, Waxman’s ambitions are increasingly global.

“You can pull up your phone in Australia and watch NBA games,” Waxman says.

“You can go on social media and engage with fans and athletes, which has broken down walls.

The Spurs were a midmarket team but now have a global audience.

We have [French-born Spurs star] Victor Wembanyama, and the NBA just announced the Spurs will play two games in Paris next year.”

Besides the Spurs investment, Sixth Street has stadium and broadcast deals with Spanish soccer behemoths Real Madrid and Barcelona, respectively.

And it has a majority stake in Legends, which does food, beverage, merchandise, retail, and stadium operations for the Dallas Cowboys, the New York Yankees, and others.

Waxman is also keen on women’s sports, pointing out that 99% of advertising, sponsorship, media, and investment dollars go to men’s sports, whereas 80% of household purchases are made by women.

“In my 20-year career, I’ve never seen anything as asymmetric as women’s sports,” he says.

Last year, Sixth Street, along with soccer superstars Brandi Chastain and Aly Wagner and former Meta Platforms Chief Operating Officer Sheryl Sandberg, paid $53 million for the rights to Northern California’s Bay FC women’s soccer team.

Professional sports teams in America used to be owned mostly by local wealthy businessmen—like the apocryphal guy with a string of car dealerships.

Now, as the prices of teams have soared with this influx of investment firms, that era is going, going, gone.

Baseball’s Pitch

This extends to Minor League Baseball, too.

In September, former Time Inc. CEO Don Logan sold the Birmingham Barons, a Double-A affiliate of the Chicago White Sox, after 18 years of ownership.

(Willie Mays and Reggie Jackson were notable Barons.

So was Michael Jordan, though his tenure was less successful.)

“We liked baseball, and we thought it’d be great for the city of Birmingham to pick up the pace a little bit.

It wasn’t brain surgery,” Logan told me.

“This group made an offer to buy the team, and we wound up taking it.

There are lots of changes in the industry now.

[The buyer] has a different business model.”

The buyer Logan refers to, Diamond Baseball Holdings, or DBH, owns 34 minor league teams—from the Albuquerque Isotopes to the Worcester, Mass., “WooSox.”

There are 120 minor league teams in North America, ergo, DBH has 28.3% of them.

“MLB sees in us people who really understand Scranton and Des Moines,” DBH co-founder Pat Battle told The Athletic.

“They’re not the 30 major markets, but they’re real markets, and very important communities in this country.”

And who owns Diamond Baseball Holdings?

Silver Lake, which (besides its Manchester City stake) holds a number of other sports properties through its portfolio company, entertainment conglomerate Endeavor.

That includes TKO, which comprises UFC (Ultimate Fighting Championship) and WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment), as well as PBR—“the world’s premier bull-riding organization”—and EuroLeague Basketball, which manages Europe’s top men’s basketball league and competitions.

Last year, billionaire Marc Lasry sold his stake in the Milwaukee Bucks, but the CEO of investment firm Avenue Capital is hardly exiting the sports business.

In fact, Lasry has launched a dedicated sports fund —which counts athletes Stephen Curry, Candace Parker, Michael Strahan, and Lindsey Vonn as partners—and has invested in golf, sailing, and a bull-riding team.

“You want to be invested in sports, whether you do it with us or you do it with somebody else,” Lasry told a group of well-heeled investors at the Milken Global Conference in May.

“You’re gonna make quite a bit of money in sports over the next few years.”

Private-equity group Arctos Partners had raised $7 billion in two sports-only funds that have stakes in a couple of dozen teams.

Sports funds are generally for institutional investors only, although some wealth managers can provide access by pooling investments from their well-heeled clients.

Matt Brown, CEO of investing platform CAIS, which facilitates retail investors buying into private equity through their financial advisors, aims to make the funds more accessible.

“There’s a willingness on the part of leagues to allow for the democratization of professional sports,” Brown tells me.

“We are actively exploring opportunities to bring sports investments [for retail investors] on to our platform.”

If sports eventually does become an asset class, it won’t be for the faint of heart.

Like elite athletes, investors will need all kinds of fortitude to realize the thrill of victory and avoid the agony of defeat.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario