Trump Hates Bidenomics. Why He Can’t Dump It.

Swing states and Republican areas are getting jobs and money from Biden’s economic plan. What’s at stake if Trump takes the presidency.

By Joe Light

Heading into the fall campaign, Joe Biden needs to convince voters that the economy is looking strong and hope they look past a blight on his presidency: higher inflation and interest rates that seem here to stay.

As Donald Trump sees it, things couldn’t be worse: “On day one we will throw out Bidenomics” and reinstate “MAGAnomics,” he said at a recent rally in Freeland, Mich.

Voters in November will settle the debate over Biden’s legacy.

No matter who wins, though, Bidenomics won’t be easily dismantled.

And it will ripple through the economy for years.

The president signed three monumental bills into law: the Bipartisan Infrastructure Deal in 2021; the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, known as the IRA; and the Chips and Science Act of 2022.

Altogether, the laws are steering more than $1 trillion into the economy through subsidies, tax breaks, and financial incentives for consumers and businesses.

Democrats compare Biden to the transformative presidencies of LBJ and FDR.

Republican groups such as the conservative Heritage Foundation denounce Bidenomics as “big government socialism.”

Political rhetoric aside, the effects of Bidenomics are everywhere.

Inflation remains a problem—arguably because of so much stimulus— while wage growth hasn’t kept up and interest rates have jumped, souring many voters on Biden’s record.

But the economy is hardly ailing.

Unemployment is near record lows, and gross domestic product has expanded more than 3% a year on average over the past three years, after adjusting for inflation, beating most other developed countries.

Chalking it all up to Biden’s policies would be a stretch.

His term coincided with the rise of artificial intelligence, unleashing a wave of tech investment, and the economy benefited from pent-up demand after the pandemic-induced slowdown.

The economy has also proven remarkably resilient and dynamic, overcoming higher interest rates and financing costs for consumers and businesses.

Some of Biden’s major economic legislation also had bipartisan backing: The 2021 infrastructure deal and 2022 Chips Act—the latter fueling a surge in U.S. chip manufacturing by the likes of Intel and Micron Technology —both passed Congress with Republican support.

Even if Biden loses in the fall, his legacy will persist.

A big reason is the IRA, a law Democrats hail as the biggest climate bill in history, both for the scope of its ambition and hopes it will create long-lasting economic and environmental gains.

Despite its name, the IRA wasn’t about taming inflation.

It was a climate package meant to supercharge the U.S.’s clean-energy transition.

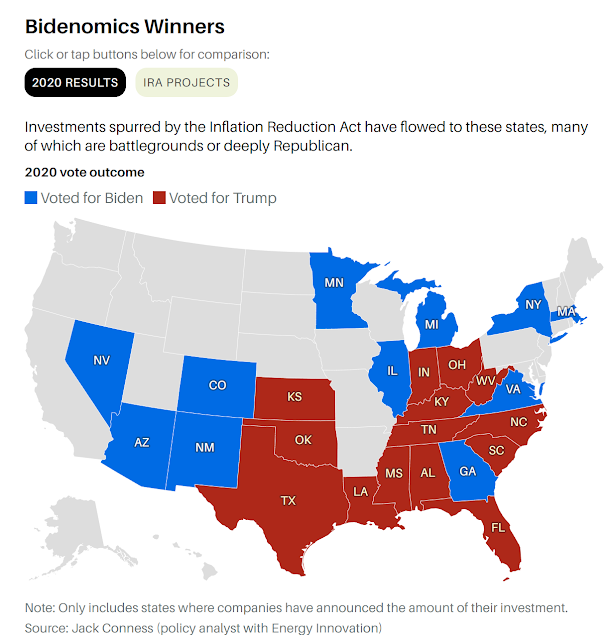

It is now benefiting many battleground and heavily Republican states—making it hard for GOP politicians to chip away or repeal it.

And it is fueling growth in industries from autos to energy, subsidizing capital-intensive projects that will last well beyond the next presidency.

“The folks on Capitol Hill refer to the IRA as Obamacare 2.0.

Republicans talk about repealing it, but when the vote happens, they won’t be able to pull it off,” says Raymond James analyst Ed Mills.

Two years after its passage, the money is flowing: Through March, the IRA has helped fuel 154 projects and $106 billion of investments in clean energy, according to Jack Conness, an energy policy analyst for think tank Energy Innovation.

Last year, all clean energy and transportation investments, including consumer purchases like electric vehicles and solar energy systems, swelled to $239 billion, according to research firm Rhodium Group.

Among its many provisions, the IRA doles out incentives for companies to build batteries, solar panels, and all manner of green technology.

Utilities can get tax credits for things like renewable-electricity power plants and wind turbines.

Subsidies are flowing through the auto industry to encourage EV adoption and domestic manufacturing.

Republicans have long opposed such initiatives, partly on ideological grounds.

A perpetual argument is that climate and clean-energy spending is inefficient, raising taxes and costs without enough economic payoff.

Trump, who has called climate change a “hoax,” describes the IRA as “the biggest tax hike in American history.”

That isn’t accurate, but a big part of Bidenomics has involved raising taxes and additional sources of government revenue to fund investment in clean energy and other areas of the economy.

The IRA, for instance, created a corporate minimum tax for companies with more than $1 billion in annual profits.

It lowered some prescription drug prices, which is expected to save Medicare hundreds of billions of dollars.

A new excise tax on stock buybacks could raise tens of billions more.

None of that sits well with Republicans, especially since the IRA’s costs have ballooned.

In 2022, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated the law’s climate and energy provisions would cost $391 billion over 10 years.

But some tax credits weren’t capped in the bill, and have proven more popular than estimated.

The original estimate, for example, used figures suggesting annual sales of EVs would reach 642,000 units in 2031.

Based on the recent pace of sales, that estimate has grown to 2.3 million, qualifying more vehicles for tax credits.

Those types of things have pushed the CBO’s 10-year cost estimates for the IRA closer to $800 billion.

There’s still political uncertainty around how long the money will last.

Companies trying to plan multibillion-dollar projects don’t know how much the government will subsidize after the election, impacting both U.S. and foreign-based multinationals considering whether to invest in the U.S.

“Companies that were looking solely to the tax credits as a reason for coming have taken a wait-and-see approach,” says Mona E. Dajani, global co-chair of the energy, infrastructure , and hydrogen teams at law firm Baker Botts.

For hydrogen-fuel companies, the election will be critical. Hydrogen is a clean-burning fuel, but making it often produces carbon emissions.

The IRA subsidizes production at up to $3 per kilogram.

That can cut costs for some producers close to zero, but many companies want the White House to ease rule proposals so that producers qualify for more subsidies.

Time is now running out, and it looks like the rules won’t be finalized before the election, says Plug Power CEO Andy Marsh, whose firm builds hydrogen production and delivery systems and started making liquid hydrogen at a plant in Georgia this year.

“The question is, will they want to implement anything done under a Biden administration,” says Marsh, referring to a possible Trump presidency.

Trump could lighten regulations or slow-walk final rules.

“You just hope that the approach isn’t, ‘If Biden did it, it’s bad,’” Marsh says.

Like Obamacare—attacked by Republicans for more than a decade after it passed—the IRA is at the top of the GOP’s agenda for a repeal.

Project 2025, run by the Heritage Foundation, has published a book amounting to a to-do list for the next Republican president; it urges the IRA’s repeal and “rescinding of all funds not already spent by these programs.”

Yet even if Trump wins and Republicans take over Congress, companies aren’t likely to abandon projects funded with IRA money.

Consider the investments already made in Michigan, a major battleground state.

Our Next Energy, a start-up within a couple of hours’ drive of Trump’s stop in Freeland, has committed $1.6 billion to building battery cells, citing the IRA.

Nel Hydrogen, another start-up, says it will spend $400 million on a facility, creating 500 jobs.

The auto industry will also see lasting changes from Biden’s legacy.

Environmental Protection Agency rules on fuel efficiency and carbon emissions are prompting auto makers to invest in EVs and batteries.

And the IRA incentivizes U.S. production by making EV rebates contingent on domestic manufacturing.

The changes are prompting car makers to ramp up factories in America.

Ford Motor plans by 2026 to open a plant making batteries for EVs, thanks partly to IRA subsidies, estimated to cost around $2 billion.

Hyundai and SK On are spending $5 billion on a battery plant in Georgia, while Toyota Motor is developing a $13.9 billion EV-battery factory in North Carolina.

Perhaps crucially for the IRA’s future, projects getting IRA tax credits are flowing to many Republican-friendly areas.

Companies are investing more than $74 billion in counties that voted for Trump in 2020, Conness’ data show.

That isn’t by orders from the Biden administration; it’s more that states like Georgia, North Carolina, and Texas happen to be more business-friendly, luring companies to set up factories.

“The IRA benefits both sides of the aisle,” said NextEra Energy CEO John Ketchum on an earnings call earlier this year.

“It’s flowing to Republican states, and it’s flowing to parts of those states that are really difficult to stimulate economically.”

The Trump campaign didn’t respond to a request for comment.

A White House spokesman, Angelo Fernández Hernández, issued a statement to Barron’s saying that “extreme Congressional Republicans would hurt their own constituents” by repealing the IRA.

Even if Biden loses, odds are that most of the IRA will stay intact.

Repealing the law or parts of it would require a Republican sweep of Congress and the White House, a prospect that many analysts think is unlikely.

Even then, it would only take a handful of defections from lawmakers whose districts are receiving billions in IRA-linked money to scuttle a repeal.

Republicans could still nix some of the most-hated provisions.

In more than a dozen bills that Republicans introduced last year to gut the IRA, the most popular targets included incentives for EVs, rooftop solar panels, and EV charging, according to policy analysis firm Capstone.

Subsidies for nuclear, hydrogen, carbon capture, clean fuels, and manufacturing were left relatively untouched.

Republicans might also target IRA subsidies to rein in spending as part of another fight: preserving the 2017 tax cuts, many of which are set to expire in 2025.

Republicans need to pay for their extension, making next year a ripe time to revisit IRA subsidies, says the policy analyst Mills.

Trump could constrain the law through executive rule-making.

Part of the IRA’s rise in costs arose from generous interpretations of who qualifies for subsidies.

The $7,500 EV credits, for example, are ineligible for cars containing some minerals from companies controlled by foreign adversaries like China.

But the Biden administration gave automakers a two-year reprieve for some materials.

“A Trump administration would likely enact stricter guidance for receiving IRA tax credits, reducing total funding in that manner,” said Mizuho analyst Brett Linzey in a research note.

Even Trump, though, might find most of the IRA too popular to kill since some of its biggest beneficiaries are deeply red Republican districts.

Bartow, Ga., for example, voted for Trump in 2020 by a 51-point margin, but is now enjoying the fruits of the battery plant being built by Hyundai and SK On.

“Some of these Republicans in places like Georgia, South Carolina, and Tennessee won’t want to upset a law that has brought their districts millions of dollars and jobs,” says TD Cowen analyst John Miller.

Whether or not MAGAnomics settles in, it may have to coexist with Bidenomics.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario