Trump’s DJT Stock Boosts His Net Worth by Billions—and Raises Big Questions Ahead of the Election

Melding business and politics, Donald Trump’s newly public social-media company could help him in the presidential election.

By Matt Peterson

Trump Media & Technology Group completed its journey to the public markets this past week, merging with a blank-check company that changed its ticker symbol to DJT.

Investors greeted the new entity warmly, but the share listing will have ramifications far beyond the relatively small corner of Wall Street that it touches.

DJT, which began trading on Nasdaq on March 26, already has gained 24%, endowing Trump Media with a market value of $8.4 billion, notwithstanding its scant revenue and history of losses.

The company has the potential not only to enrich its shareholders, prominently including former President Donald J. Trump, but also to affect the U.S. presidential election in November.

The rapid gains in Trump Media shares added billions of dollars to Trump’s net worth in a matter of days, at a time when he is facing pressure to come up with cash to resolve his legal disputes.

It will be complicated for him to access that wealth in the short term, but the insider selling restrictions related to the company’s public listing will ease before the November election.

Meanwhile, Trump’s significant holdings in a public company give individuals, companies, and even governments a new, direct path to influence the candidate’s bottom line.

There are many rules governing political donations to candidates and their fund-raising organizations, but far fewer checks on buying shares in a company controlled by a candidate.

There is no precedent for a presidential candidate gaining so much wealth, so quickly, and in this fashion months before an election.

Trump Media announced plans in 2021 to merge with Digital World Acquisition Corp.

In 2022, Trump Media launched Truth Social, the social-media network.

The merger closed on March 25, 2024, with Trump as the controlling shareholder via his ownership of 78.8 million, or 58.2%, of the shares.

As the merger prospectus suggests in an 84-page section on risk factors, Trump Media is no blue chip.

The company had to reissue its 2021 and 2022 financial statements due to “material weaknesses in its internal control over financial reporting,” the prospectus states.

Those weaknesses, it notes, “continue to exist.”

In June 2023, a former DWAC director was arrested by the Department of Justice and charged with insider trading; he and others in the case have pleaded not guilty.

Last July, DWAC agreed to pay $18 million to settle a Securities and Exchange Commission antifraud investigation.

The company said that the settlement “would remove the cloud of uncertainty lingering over DWAC.”

Trump Media investors have stuck with the company, even with knowledge of the risks.

Devin Nunes, a former Republican congressman from California who is now the chief executive of Trump Media, recalled a moment in October when the share price of Digital World had fallen as low as $12 or $13.

“What we found is that people didn’t care,” Nunes said in an interview on the Sean Hannity radio show on March 26.

“Even if they’d bought in higher, they never sold.”

Trump Media didn’t respond to requests to make Nunes available for an interview, or answer detailed questions posed by Barron’s in an email.

A spokesperson criticized Barron’s reporting in a short response to the questions.

Trump didn’t respond to requests for an interview or emailed questions.

The disclosure of so many risk factors serves to inoculate Trump Media against the risk of running afoul of securities laws, says Howard Fischer, a partner at the law firm Moses Singer and a former senior trial counsel with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

“If things go south, one could argue in defense that no one was misled about the financial prospects of the company because all of those were disclosed,” Fischer says.

“And if people wanted to be part of a cultural phenomenon rather than an economic one, why should the company be liable for that?”

The stock’s early gains suggest that people can be both, supporting Trump while also enriching themselves.

“We’ve never had a situation in which the economic and political interests of a figure have combined in this way,” Fischer says.

The past four years have been challenging for Trump, although his brand appears to have benefited from his travails.

First, there was the loss of the presidency and thwarted efforts to disqualify President Joe Biden.

Then came a string of indictments and legal rulings resulting in hundreds of millions of dollars of fines.

Trump is in the process of appealing some of those fines and says he plans to appeal others.

Now, court trials await.

The successful public listing of Trump Media is a win for the former president, however.

At the least, it gives him a vehicle through which to enhance his wealth.

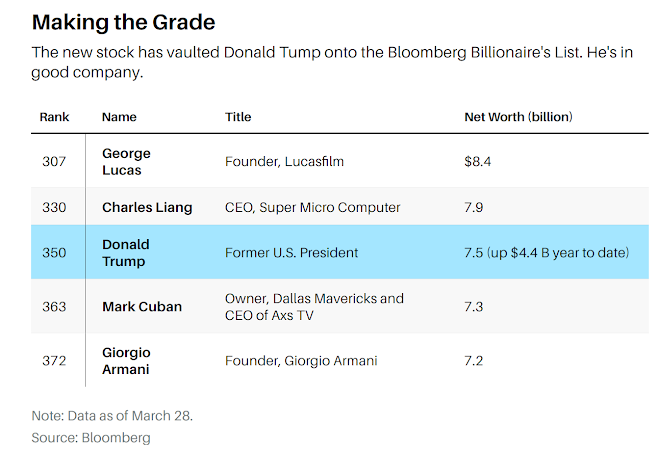

The merger catapulted Trump into the Bloomberg Billionaires Index for the first time, and the rally in the shares has added $3.4 billion to his net worth, a Barron’s analysis found, although these are paper gains for now.

Trump’s shares were worth $4.9 billion as of Thursday’s close, with the stock trading at $62.

The listing also changes the composition of Trump’s wealth from largely illiquid assets, chiefly real estate–related, to equity holdings that can be monetized more easily once initial trading restrictions lift.

Estimates before the launch of the DJT ticker put Trump’s wealth in the range of $2.3 billion to $3.1 billion.

Barron’s recently estimated the worth of Trump’s 30% share of a Manhattan office building, 1290 Sixth Ave., at about $300 million, but noted that accessing that value would require the agreement of the majority owner of the building.

Trump’s newfound wealth could be a political asset and a financial one, highlighting his business savvy to an electorate anxious about the economy and the nation’s finances.

“He’s definitely going to use it to reflect his power and might, and that it’s because of the supporters that have helped him,” says Ron Bonjean, co-founder of the public-relations firm ROKK Solutions and a longtime Republican communications strategist.

“That can make a difference on Election Day, as well.”

“Truth Social is doing very well,” Trump said on March 25 at a news conference following an appellate court ruling that he needs to post a $175 million bond to appeal his New York fraud judgment, down from an initial $454 million.

“It’s hot as a pistol and doing great.”

Then, he started to complain.

Trump Media is listed on the tech-heavy Nasdaq, not the New York Stock Exchange.

“We can’t do the New York Stock Exchange,” he said.

“You’re treated too badly in New York.

The people at the New York Stock Exchange are very upset about it.”

The NYSE has said it would welcome Trump’s listing.

Trump’s ability to turn gold into grievance, and vice versa, is another thing that makes Trump Media’s public listing a potentially potent political tool.

Trump has often said that when state institutions come after him, they are really coming after his supporters—he is just standing in the way.

The stock allows supporters who invest in the company to have a direct financial stake in his personal and political fortunes.

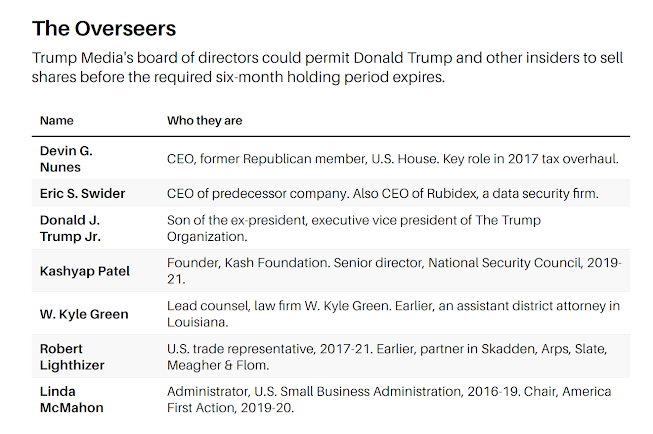

Among Trump Media’s seven directors are several political allies of Trump: Nunes, the former California congressman; Robert Lighthizer, who served as U.S. trade representative in his administration; Kash Patel, a former National Security Council official; and Linda McMahon, a former head of the Small Business Administration. Trump’s son Don Jr. is also on the board.

The nexus of politics and finance has made the terms of Trump’s holdings in Trump Media a source of speculation.

Trump and other early stockholders are barred from selling or lending their stock for the first six months after the blank-check merger closed.

The board could alter the terms that govern sales or loans, but doing so could pose legal and political challenges.

If the directors opt to allow Trump to sell stock early, their pre-existing relationships to Trump could become a legal liability, Fischer said.

“Will they do so because it’s in the best interest of shareholders, or because they believe it’s in the best interest of Donald Trump?” he said.

With his bond to New York state reduced, Trump might have less need for immediate cash.

Regardless, Trump and others will be permitted to start selling shares once the lockup expires in September.

If he and other early shareholders begin to sell shares then, causing the stock to decline, voters are likely to notice.

Bonjean doesn’t think that will be an issue.

“If the company ends up declining after six months, he will likely blame it on large institutional investors that are taking advantage of individuals and families that put their money into this stock,” he says.

“This is a huge opportunity for Trump to take advantage of both financially and politically that we haven’t seen a political figure do ever in American history.”

Trump will have opportunities to flog the stock at campaign rallies and media appearances before the November election.

He is legally entitled to promote it, according to Fischer, the former SEC attorney, and probably will get wide latitude when he boasts about its greatness.

That’s despite Trump Media’s financials: The company generated revenue of only $3.4 million in the first nine months of last year, primarily from advertising.

That isn’t nearly enough to cover operating expenses of $10.6 million and interest expenses of $38 million in the same span.

Plenty of candidates have had business interests on entering office, and some presidents have embraced the opportunity to profit from their personal brand.

Consider President Barack Obama’s best-selling books, for one.

(Obama donated much of the proceeds he received while president to charity.)

Still, no other leading candidate for president has launched a public company under his name in the months before an election.

The idea of a presidential candidate—and potentially an officeholder—having a major stake in a public company tied to his brand is troubling to some ethics watchdogs such as Virginia Canter, chief ethics counsel at Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington.

An investor who might seek to gain access through stock purchases “is putting money” in the candidate’s pocket, she said, noting that this approach is “so much more direct” than a campaign donation.

CREW filed a lawsuit against the Trump administration, alleging that Trump had received payments from foreign governments, which the group argued violated the Constitution’s foreign-emoluments clause.

The Supreme Court dismissed the case in 2021 on the grounds that he had left office.

As of December, Susquehanna International Group, co-founded by GOP megadonor Jeff Yass, owned about 2% of DWAC’s shares, according to regulatory filings.

Susquehanna is also an investor in ByteDance, the China-based owner of social-media network TikTok.

Trump recently surprised observers by saying that he didn’t want to see TikTok banned, after trying to ban it during his presidency.

There is no evidence that these developments are connected.

Susquehanna told the New York Times that its role in Trump’s company was as a market maker, suggesting that it didn’t see its shares as a long-term investment.

It is unclear whether Susquehanna still owns the shares.

The company didn’t respond to requests for comment.

It will be difficult to know whether political donors or companies affiliated with them purchase Trump Media’s shares, although Nunes has put the number of individual investors in Trump Media at 400,000.

Foreign investors, including sovereign-wealth funds, can largely trade freely in the U.S. stock market.

Their involvement in a given stock might be disclosed months later, if at all.

It would be difficult to make the case that Trump supporters’ stock purchases run afoul of campaign-finance law, says Shanna Ports, senior legal counsel for campaign finance at the Campaign Legal Center.

It would be tough to prove, she says, that people are investing in Trump Media “to support his candidacy as opposed to seeing an investment opportunity.”

Trump once said that his net worth goes up and down based on his feelings.

That could now include his feelings about Trump Media’s stock.

A campaign rally could drive a stock rally, which might drive up Trump’s net worth.

All presidential candidates tell voters that their financial fortunes are tied to the candidates’ political fortunes.

With Trump Media, Trump is making the link explicit for those who choose to invest.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario