The World’s Largest Buyer of U.S. Debt Isn’t Going Away

The end of zero-rate policy in Japan seems like a risk to American bonds. In fact, they may already have passed the test.

By Jon Sindreu

Could the largest foreign buyer of American debt suddenly stop buying?

Here is a comforting thought: This problem is probably already behind us.

At a time when government issuance is massively expanding and firms face a 2025 refinancing cliff, overseas investors have gone from holding 43% of U.S. debt a decade ago to holding just 30%.

Adding to the worries, the Bank of Japan might start raising interest rates next year, giving some Japanese owners a reason to repatriate their money.

The BOJ was alone among top central banks in leaving rates near zero even as inflation surged in recent years.

The yen plummeted as money fled Japan, recently reaching its lowest level since 1971 in inflation-adjusted terms, data by the Bank for International Settlements shows.

BOJ Gov. Kazuo Ueda, who succeeded the ultra-dovish Haruhiko Kuroda in April, has started to buckle under the pressure.

Ueda has been gradually dialing down his predecessor’s “yield curve control” policy.

The yen has rebounded a bit over the past two weeks, suggesting that markets expect yields in Japan to keep rising.

For all the focus on China, Japan is actually the top holder of U.S. sovereign debt, with a total of $1.1 trillion.

The BOJ’s ultraloose monetary policy, now almost three decades old, created what analysts sometimes call the world’s biggest carry trade: Traders borrow yen at no cost, swap it for the currencies of countries that pay higher rates, and buy assets there to earn a pickup.

U.S. Treasurys, corporate bonds and loans are obvious targets, given their high yields and relative safety.

Kazuo Ueda became the head of the Bank of Japan in April. PHOTO: KYODONEWS/ZUMA PRESS

But rest easy: Japan isn’t about to stop financing the U.S. government.

Many of the institutions that participate in this carry trade, including banks and some pension funds and insurers, avoid owning foreign currencies and use derivatives to hedge out the exchange-rate risk.

They don’t care about the headline gap between U.S. and Japanese rates, but instead the gap after hedging costs.

As the unhedged pickup of Treasurys over Japanese bonds has hit new highs, the hedged pickup has become deeply negative and plumbed new lows.

This is because of how this hedging is done, usually by rolling over three-month foreign-exchange swaps, which is an implicit bet on the shape of the U.S. yield curve.

Since U.S. rates have risen more than Treasury yields—the yield curve has inverted—hedging costs have skyrocketed.

Appearances aside, this popular carry trade has been a money-losing strategy since July 2022.

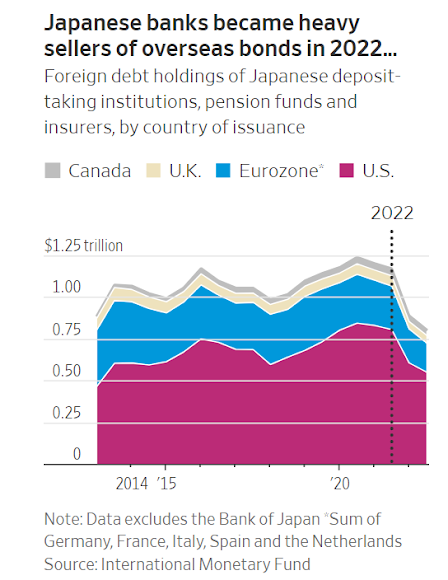

Their holdings of U.S. bonds amounted to $550 billion at the end of 2022, from $840 billion two years prior.

They have also dumped the bonds of the top-five eurozone countries, with their holdings dropping to $170 billion from $290 billion.

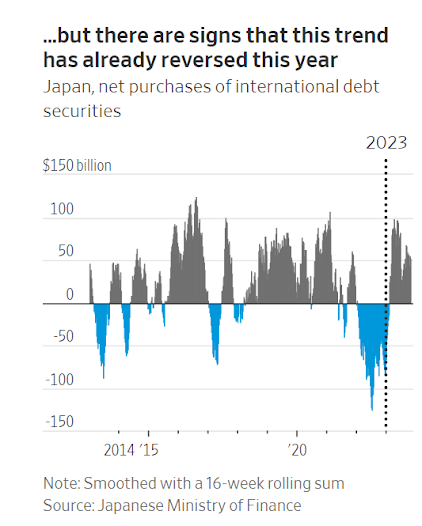

Yet more up-to-date figures from the Japanese Ministry of Finance suggest that the selling flow has already reversed this year: Japan is again a net buyer of international debt.

This may be because hedging costs have cheapened slightly since the summer, as Treasury yields have risen relative to U.S. rates.

Further steepening of the U.S. and German yield curves could offset whatever policy tightening the BOJ might deliver, especially since the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank may have finished raising rates and could even start cutting them at some point.

To be sure, some deep-pocketed Japanese institutions could move funds back home, because they don’t hedge their holdings.

These include the officials who manage the country’s foreign reserves, as well as the mammoth Government Pension Investment Fund, which holds roughly $360 billion in foreign bonds and, according to a 2019 report, only hedges about 5% of them.

Still, these steady investors haven’t really loaded up on U.S. bonds in the past two years, when the gains from doing so were massive.

So it is hard to see why they would now shift rapidly in the other direction.

Fixed-income investors face many challenges, but it doesn’t look like Godzilla is one of them.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario