PC Sales Are Ready to Take Off Again. It’s All About AI.

AI's big opportunity goes beyond the cloud. How to play the future of PCs.

By Eric J. Savitz

As sales of personal computers soared during the pandemic, you could almost hear PC makers saying, “We told you so.”

For years, laptops and desktops had remained technology’s workhorse, even with most of the industry’s attention moving to smartphones and the cloud.

With everyone stuck at home in 2020 and 2021, global PC sales surged nearly 25%.

Then offices reopened and the upgrade cycle came to an abrupt halt.

By 2022, PC sales were falling once again.

This time, PC makers like Dell Technologies (ticker: DELL), HP Inc. (HPQ), and Lenovo Group (LNVGY) are taking a different approach to rev up sales: The PC business is going all in on artificial intelligence.

“The killer app of AI,” says Dell Vice Chairman Jeff Clarke, “will be that you’ll love your PC again.

The working theory of AI has been that it requires big, powerful computers, driven by hard-to-find graphics processors, primarily from Nvidia (NVDA).

All of that computing—the creation of large-language models plus their continuing use—happens in the cloud.

Meanwhile, laptops, desktop PCs, and even mobile phones become simply access points to the cloud, where AI services like ChatGPT do their computationally intensive magic.

Even before AI, consumer and business laptops had largely become dumb terminals for using online platforms from Amazon.com (AMZN), Microsoft (MSFT), Alphabet‘s (GOOGL) Google, Meta Platforms (META), and Apple (AAPL).

Documents are in the cloud, email is in the cloud, photos are in the cloud, music is in the cloud.

“The network is the computer,” Sun Microsystems computer scientist John Gage presciently said 40 years ago.

PC makers are looking to change that paradigm.

They are readying AI personal computers, with the first models set to arrive in the next few months.

The microprocessor companies are excited, too.

The common goal is to enable PC users to run generative AI applications right on their desktops, whether connected to the network or not.

“We look at it as an opportunity to make the PC an uber-companion for how people get things done,” says Sam Burd, president of Dell’s Client Solutions Group, which includes its PC business.

“They are going to be better, more productive devices for both corporate environments and for people at home.”

Alex Cho, president of HP’s Personal Systems Group, goes further: “It will be a real inflection point for the category.

There will be dramatically new use cases, benefits, and experiences.”

Intel has talked extensively about the opportunity in AI PCs; the company will launch a chip code-named Meteor Lake, its first processor with an integrated neural processing unit, this December.

Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) CEO Lisa Su has been promoting AI at least since her January keynote address at CES, the giant annual tech trade show in Las Vegas, where she launched a new generation of processors with built-in AI capabilities.

Qualcomm (QCOM), which licenses chip designs from newly public Arm Holdings (ARM), is ramping up its push into the PC processor market, with the potential to steal away market share from the market leaders.

The company detailed its plans for AI PCs at its recent developers conference.

As consumers and businesses have learned in the 11 months since the launch of ChatGPT, generative AI allows once-unimaginable tools for the creation of text, images, video, and music.

For businesses, the technology offers more intuitive and powerful ways to use corporate data to better serve customers and improve productivity.

It’s no surprise why the PC makers want in on the action: Research firm IDC recently forecast that enterprise AI spending would reach $143 billion by 2027, with a compound annual growth rate of more than 73%.

That’s a huge opportunity for a PC industry that hasn’t shown sustained growth for years.

The pandemic-era work-from-home trend triggered a big but ultimately misleading surge in PC demand. Global shipments reached 342 million in 2021, a 23% spike from prepandemic days, according to Gartner data.

PC shipments were 279 million in 2019.

PC manufacturers were optimistic the surge marked a global reset—that the crucial role laptops played in keeping the economy going during the Covid era would quicken the industry’s refresh cycle and continue to boost the number of laptops owned per household.

But PC sales have now declined for eight quarters running, retreating to their prepandemic trough.

Gartner estimates PC shipments will decline to 245 million this year.

The industry needs a spark, and it sees one in the AI PC.

There are other factors that will provide a small boost to PC growth even before the benefit of AI fully kicks in.

Microsoft is terminating support for Windows 10 in October 2025, which will spur some upgrade demand from corporate buyers, according to Gartner analyst Mikako Kitagawa.

There’s also the fact that all of those pandemic-era PCs are beginning to age out.

Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger said on the company’s recent earnings call that he sees the market rebounding to 300 million units.

Gartner is projecting 5% unit growth for the PC business in 2024.

The pandemic, at the very least, proved that people still rely on PCs. The AI opportunity is sending the PC industry back to its innovative roots.

AI PCs won’t look different than the one now sitting on your desk.

But on the inside, they’ll have a system-on-a-chip that includes three important elements: a conventional CPU, or central processing unit; a GPU, or graphics processing unit; and—here’s the new wrinkle—an NPU, or neural processing unit.

Neural processing is a way of processing very large data sets efficiently.

And the NPU will pick up most of the AI-specific computing requirements.

Apple has been including a neural engine as part of its homegrown processors since it introduced the A11 processor in the iPhone 10 in 2017.

This past Monday night, Apple unveiled its latest MacBooks during a rare prime-time event, a sign of its renewed focus on its own PC division.

The latest MacBook Pros, along with an upgraded iMac, will all use a version of the company’s new M3 processors.

Apple said the high-end version of the chip, called the M3 Max, will be capable of running complex AI workloads.

Meanwhile, most modern laptops already use some level of artificial intelligence and machine-learning techniques, like facial recognition, autofocus, fingerprint scanning, noise cancellation, and image enhancement.

“We have been embedding AI in our products for years,” says Daryl Cromer, chief technology officer for PCs and smart devices at Lenovo.

“They’ve led to better devices.”

But those use cases are the AI equivalent of the human nervous system—things that happen in the background of computing that improve the experience.

New PCs will bring artificial intelligence to the forefront.

HP’s Cho imagines myriad new applications, ranging from AI software providing real-time coaching for game players to real-time language translation on conference calls.

He sees AI PCs reaching 40% to 50% of laptop sales within three years.

PC leaders now cite a long list of reasons to bring AI directly to the computer.

The first one is privacy.

Sending data into the cloud to be sorted by AI applications carries real risk that the information could be used or disclosed in unintended ways.

For chief information officers, the most compelling reason is cost savings.

Running AI software on the cloud is expensive, and anything that can shift some of that burden to the edge of the network should save money.

Dell’s Burd sees the emergence of smaller AI models that can run on PCs, which would also mean lower latency—with no delays for communicating back to the cloud—and higher speed.

“The edge of the network is where data is being generated, and that’s where AI is going to happen,” he says.

Lower latency is a particular boon for gaming applications, which could use AI to make the “nonplaying characters” that fill fictional worlds into conversational personalities.

And, not least, running workloads locally makes it possible to run AI software even when not connected to a network at all.

(No one wants to rely on the cloud for a facial ID feature, for instance.)

Burd thinks applications like Microsoft 365 Copilot, which adds AI functionality to applications like Word and PowerPoint, will eventually run on PCs, rather than in the cloud.

Microsoft, a key provider of both cloud computing and PC software, declined to be interviewed for this story.

Robert Hallock, senior director of technical marketing at Intel, notes that PC processors have taken on more functionality over time, adding graphics, video encoders, and other features.

By adding a neural engine to the processor, he says, you gain “more performance and efficiency—and unlock new things.”

Those new things are still largely theoretical, though no one knew that 4G wireless would eventually power services like Uber and DoorDash.

Rakesh Anigundi, an AMD director who leads the team building the company’s Ryzen AI chips, is convinced the trend will accelerate the refresh rate.

“It makes PCs exciting again,” he says.

Patrick Moorhead, CEO of Moor Insights & Strategy, says having apps and data on devices provides an experience that is both faster and more reliable.

AI applications will be “a whole lot quicker” without having to upload data to the cloud.

There are still plenty of PC skeptics, though, and for them, the AI conversation has pushed PCs even further to the margins.

The consensus view has been that the computational power required to create and run large-language models would almost certainly have to run in the cloud.

GPT-4, the latest model from OpenAI, has 1.76 trillion parameters—and it can take weeks of intensive computing to produce new models.

The need for massive computing power to run these models explains the rapid growth in demand for Nvidia’s graphics processors, which have become the default for AI applications.

The firm’s H100 chip costs $30,000, not a part that will work on a laptop.

Yet it turns out that a substantial portion of AI-related computing can be brought back to the laptop more efficiently, securely, and affordably.

One example of what’s possible comes from Rewind AI, a start-up backed by the venture firms Andreessen Horowitz and NEA.

Rewind runs on a laptop—on Macs today, with Windows-based PCs to follow—collecting everything a user does, recording conversations, keystrokes, documents, and websites.

That’s a privacy nightmare in the current cloud-dominated world, but it’s far less worrisome when all the data are stored and locked down on a local PC.

Rewind then makes everything searchable with a natural-language chatbot.

Rewind CEO Dan Siroker calls it a “co-pilot for your mind.”

Rewind might not be the ultimate winner, but the concept has real appeal, and it’s the type of use case that could drive adoption of new PCs.

People will start to buy PCs again when they see friends’ devices unlocking new doors and making them more productive.

Intel recently unveiled an “AI PC Acceleration program,” which is intended to jump-start applications leveraging local use of AI techniques, in areas like content creation, security, audio effects, and video collaboration.

“AI is good at generating something from nothing, or saving time in laborious human tasks,” Intel’s Hallock says.

IBM CEO Arvind Krishna says the rise of the AI PC is “a given.”

In an interview with Barron’s, he explained the history of the PC industry as a set of major chip upgrades that revolutionized the device and opened the way to new applications.

About 35 years ago, he says, Intel rolled out a chip called the 80387 that worked with x386 processors for computationally intensive applications like spreadsheets.

PCs later added GPUs, enabling games and video editing.

And now PCs are adding NPUs, for artificial intelligence.

Krishna thinks every PC before long will have the ability to run AI models with 10 or 20 billion parameters.

He imagines PCs that run electrocardiograms to check users’ heart function at home without connecting to external networks for analysis, or that use voice conversations without the need for any text input.

“It changes the market for the chip makers,” he says.

Alex Katouzian, a senior vice president at Qualcomm, says AI PCs based on Qualcomm’s Snapdragon X Elite processors will be able to run multiple AI models in the background at the same time.

He imagines, for instance, the ability to summarize text and compile a list of action items from an ongoing meeting.

Qualcomm claims that the new Snapdragon processor is faster—while using less power—than chips from Intel and AMD.

The first PCs using the new Qualcomm chips should be available next year.

Meanwhile, Micron Technology (MU), whose memory chips will be needed in new PCs, could also get an AI boost.

The DRAM maker says base level memory requirements on PCs could double.

Both Qualcomm and Micron stocks are cheap and could get boosts from any good AI news.

But when it comes to the PC rebound, investors should go straight to the source.

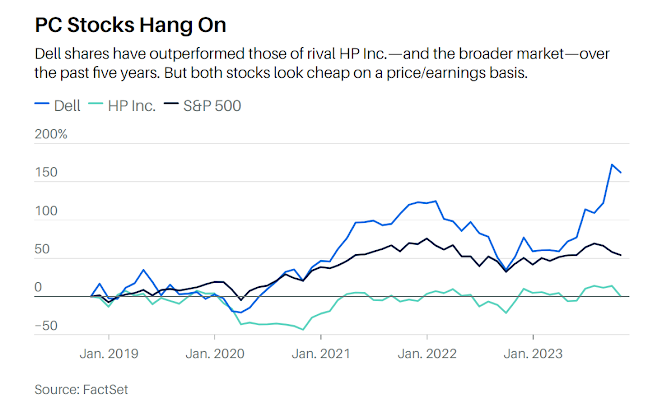

Dell and HP both have bargain-priced stocks.

HP, with more consumer exposure than Dell, trades for eight times forward earnings, less than one times 2024 estimated sales, and sports a 4% yield.

Dell, which sells PCs mostly for business and should get an AI-boost for its server business, trades at 10 times 2024 earnings estimates, less than one times sales, and offers a 2% yield.

Both are aggressively buying back stock.

We don’t need AI to tell us that the stocks look cheap.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario