Why the UAW Strike Isn’t the Biggest Problem for Ford and GM

The industrial action shines a light on the companies' place in the new world of EVs.

By Al Root

ILLUSTRATION BY NICHOLAS KONRAD

A strike is only the most immediate issue facing the two biggest U.S. auto makers.

The existential threat posed by electric vehicles is the bigger problem.

EVs are finally taking off in the U.S., but EV-related losses are growing for Ford Motor and General Motors (GM).

Now, the companies have some hard decisions to make about how they will spend billions of dollars, decisions sure to have serious consequences for their stocks.

The numbers are huge.

Ford is planning to spend roughly $7 billion over the next few years to build brand-new battery plants and EV manufacturing facilities in Kentucky and Tennessee, while GM has committed to spend $35 billion from 2020 to 2025.

All told, EV development will probably eat up roughly half of the companies’ spending on new models, plants, and equipment over the next three to four years.

It’s an enormous bet on the growth of electric vehicles—one that should be paying off.

Sales of U.S.-made battery-powered EVs rose 47% in the first half of 2023, compared with the same period of 2022, while first- and second-quarter sales for EVs were both record highs.

EVs now account for about 7% of new-vehicle sales in the U.S. and 22% in California, showing what’s possible for the rest of the nation.

The problem is, most of the rewards are flowing to just one company, Tesla (TSLA).

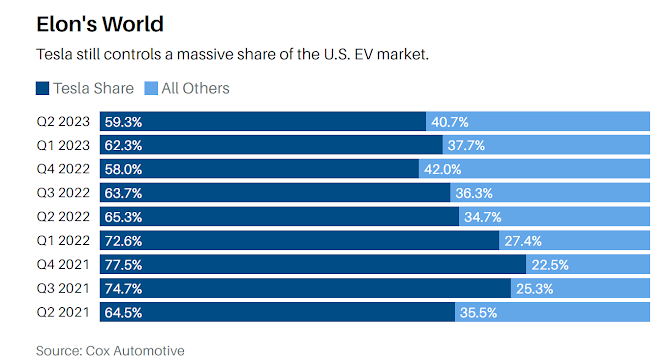

Despite big pushes by a raft of rivals, Elon Musk’s pioneering company still accounts for nearly 60% of all EV sales in the U.S., down only slightly from two years ago.

GM has managed to take just 6% of the market, while Ford has 5%.

If the two Detroit icons hope to be long-term players in EVs, which look to be the future of cars, they have little choice but to keep spending huge sums of money.

That goes a long way to explaining the intense contract negotiations with the United Auto Workers, whose members launched strikes after the 11:59 p.m. Thursday deadline expired.

Union leadership is asking for 30% wage increases over the four-year life of the new contract, to compensate for high inflation and past concessions that helped the companies through dark times.

The companies, however, say they need the money to fund their huge transition from gasoline to electricity.

The standoff probably means that GM and Ford will have to pay employees even more than what they do now in relation to nonunionized companies like Tesla and Rivian Automotive (RIVN).

“Accepting anything north of 20% pay increases [over the life of the contract] would be a tough pill to swallow for the business model of GM,” says Wedbush analyst Dan Ives.

“The winner here is Tesla and Rivian in their nonunion stance.”

In other words, Tesla could wind up with still-greater dominance of the industry.

Already, Ford and GM are absorbing big losses from their pushes into electric vehicles.

In July, Ford increased its EV division’s full-year projected loss to $4.5 billion from $3 billion, while pushing back a goal of producing roughly 50,000 EVs a month from the end of 2023 to some point in 2024.

In the U.S., Ford sold 32,000 EVs in the first seven months of the year, up 3.5% compared with 2022.

GM had a better start to 2023, selling about 36,000 EVs, up from fewer than 8,000 in the first half of 2022, though the 2022 figures were affected by battery problems experienced with the Chevy Bolt.

First-half sales increased about 15% from the second half of 2022, putting GM back in position as the second-best seller of EVs in the U.S. GM says it doesn’t expect EVs to be profitable until 2025, but it doesn’t break out figures for the division.

Tesla is the one U.S. EV maker that can accurately be called a success.

The company sells more than 58,000 cars a month in the U.S. and produces 150,000 EVs a month around the globe, dwarfing the totals that GM, Ford, and other traditional auto makers sell in a year.

Tesla is firmly profitable, with Wall Street projecting a 2023 operating profit margin of about 11%.

From inauspicious beginnings in 2003, Elon Musk launched expensive vehicles like its Roadster, Model S, and Model X before releasing the mass-market Model 3 in 2017.

The crossover Model Y followed in 2020. The Model 3 became the first battery-powered vehicle to top one million in total sales.

Tesla’s success seemed to create a blueprint for other auto makers to follow: launch high-price vehicles as a proof of concept, and follow that up with a crossover SUV to tap into America’s love of souped-up station wagons.

But the blueprint proved difficult to follow.

Everyone from start-ups to legacy auto makers assumed that producing EVs would be relatively easy.

There are fewer moving parts, simpler motors instead of internal combustion engines, and even more commonality among vehicle platforms.

The same batteries go into a Ford F-150 Lightning as a Ford Mustang Mach-E.

But production has been far more difficult than many expected.

Ford ran into some battery problems with the Lightning, which halted production for weeks early in 2023 just as sales were picking up steam.

GM ran into its own battery issues with the Chevy Bolt. EV start-ups have been hampered by production problems, as well.

“Everyone has struggled to manufacture EVs,” says Benchmark analyst Michael Ward.

“Everyone. They’re not easy.”

EV players also thought they could follow Tesla’s strategy of launching expensive vehicles, often north of $100,000, a niche that counts for roughly 2% of the overall auto market, according to data provider Cox Automotive.

The Tesla Model S and Model X, GMC Hummer, BMW i7, Lucid Air, Porsche Taycan, Mercedes EQS, and the slightly less expensive Audi e-tron Q8 and Mercedes EQE sold a combined 24,328 units in the U.S. in the second quarter.

Tesla’s X and S models captured roughly one-half of that total.

There’s just not enough of a market for nine models that are out of reach for most car buyers.

The success of Tesla’s crossover Model Y, the best-selling car in the world during the first half of 2023, spurred other auto makers to launch their own small electric SUVs.

That includes the Hyundai Ioniq 5, Kia EV6, Volkswagen ID.4, and Ford Mach-E, among others.

The proliferation makes sense: Small and midsize SUVs are among the most popular vehicles in the U.S., accounting for about 33% of all cars sold.

But something isn’t translating: The Tesla competitors sold fewer than 80,000 small EV SUVs in the U.S. over the first half of 2023, or about 1,000 per model a month on average, not nearly enough to make the economics work.

Part of the problem is that the average range of a standard and long-range Model Y is about 300 miles per charge, while the average range of the competitors’ EVs is about 240.

“At the end of the day, what consumers care about is the cost of the EV and the range,” says Eli Horton, ETF portfolio manager at activist investor Engine No. 1.

Batteries need to improve, but so does the messaging.

Ford and GM can’t use the same marketing strategies that they have used for generations to sell their traditional vehicles—and they can’t rely on the fact that the cars are better for the environment than their gas-guzzling cousins.

The Pew Research Center found that about 43% of Americans looking for a car are willing to shop for an EV.

Of those, about three-quarters lean Democrat.

“I think there is a political conversation here,” says Global X ETF research director Pedro Palandrani, though he is optimistic that EVs will knock down political walls when they finally become cheaper overall than traditional cars.

The buyers for EVs and combustion-engine cars at the same company even appear to be different: Ford says more than 60% of its EV buyers are new to the Ford brand.

That’s good for bringing in new customers, but it also means that existing Ford drivers prefer gasoline.

It means that ads have to focus on safety, cost, power, or any other selling feature.

But mostly, it comes back to making cars that people love, says Ted Cannis, CEO of Ford Pro, the company’s commercial business.

“Businesses are pretty rational [buyers]…they run Excel spreadsheets, ROI models, total cost of ownership,” he says.

“People fall in love with cars or a feature in the car…it’s emotional.”

Both companies tell Barron’s they are confident that their strategies will work.

That doesn’t mean things can’t be improved.

So, what are Ford and GM to do?

Morgan Stanley analyst Adam Jonas expects Ford to lean harder into hybrids, which Ford continues to make and which account for roughly 7% of its U.S. sales and 10% of all F-150 sales.

“We’re looking to go to at least 20% next year,” says Andrew Frick, Vice President of sales, distribution, and trucks in Ford’s traditional car business.

But Ford also makes that cars people love—the Ford F-150 and the Ford Mustang come to mind—and it’s betting they will become EVs people love.

The market for trucks outside of the U.S. favors smaller vehicles, the size of a Ford Ranger or Toyota Tacoma.

A hybrid and all-electric version of the Ranger should be a priority for the company.

It’s a market occupied only by Rivian right now with its R1T pickup.

Ford is also the largest seller of commercial vehicles in the U.S. and Europe, with roughly 265,000 fleet customers and 40% of the U.S. market, and that might give it a leg up in the race to sell EVs.

“You can see a third of that market easily being electric,” says Benchmark’s Ward.

GM, for its part, needs to target more segments of the EV market.

Its recent launches, including the GMC Hummer and Cadillac Lyriq, are priced at the higher end, and the coming Cadillac Celestiq starts north of $300,000.

GM is betting big on its EV technology investments, which will lower costs while providing longer range and more features than the competition, and it plans electric versions of the Chevy Blazer and Chevy Silverado, which are due before the end of the year.

An electric version of the lower-priced Chevy Equinox is scheduled to be released in 2024.

“I think [GM] is making great strategic decisions with vertically integrating their battery platform,” says Engine No. 1’s Horton, who once owned GM stock in the Engine No. 1 Transform Climate exchange-traded fund (NETZ), but doesn’t right now.

The challenge is to make sure those vehicles don’t go only to early EV adopters but to GM drivers who are trading in gasoline-powered cars at the end of leases or loans.

Whether that means offering free charging, free lease payments, or other radical incentives, it doesn’t matter.

“A couple of lease payments isn’t a costly incentive,” says Benchmark’s Ward.

Both companies could also take a more holistic approach to targeting EV sales.

“The industry thinks of every purchase as an independent purchase,” says Stephen Beck, managing partner at consultancy CG42.

“Auto makers need to target households.”

There is a compelling case for a least one EV per home.

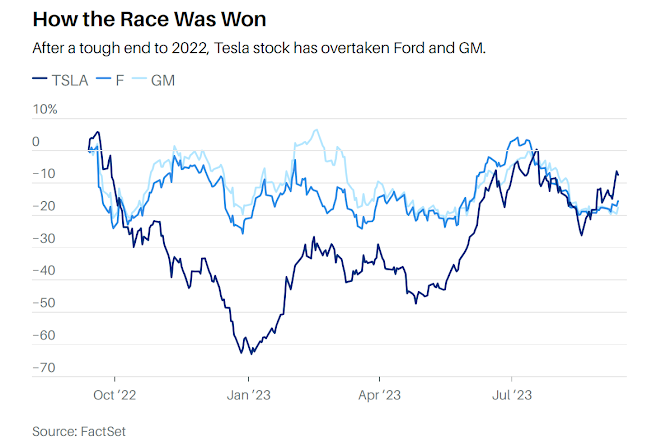

Yet there is no easy solution for shares of GM or Ford, which have fallen about 21% and 20%, respectively, over the past 12 months.

Demonstrating momentum in EV sales—which would bode well for margins—would help shift investor sentiment.

With EV profitability not due until 2025 for GM and 2026 for Ford, however, the stocks will still be dominated by interest rates and overall auto sales—assuming the strike is settled—for the next 12 to 24 months.

There is some good news on that front.

Car sales are improving, with about 15.3 million new cars sold in the U.S. over the past 12 months, up about 11% compared with the year-ago period.

If interest rates and car prices have peaked, that number should move to 16 million or 17 million units.

More volume for GM and Ford should be enough to keep profits and cash flow strong while investors wait for EV profits.

The potential rewards could be substantial if the auto makers can deliver.

Their stocks are priced, to some extent, for a disaster scenario—an EV market that never develops.

GM trades for less than five times 2024 earnings estimates, while Ford trades for less than seven times, both well below the S&P 500 index SPX‘s multiple of 18.

Those multiples imply there is essentially no growth in profits in either business and that the EV transition will, at best, be neutral to both companies and, at worst, a total loss.

That scenario is not out of the question.

John Murphy, an analyst at BofA Securities, sees the whole industry falling behind.

He had been expecting EV sales to amount to 11% of new U.S. vehicle sales for 2023, not the 7% registered in the first half of the year.

If the demand just isn’t there, a “significant amount of capital has been wasted,” he says.

“Yes, it could end up looking like a disaster.”

But Murphy and others tend to think that EVs will prevail.

In fact, some analysts project EVs could make up half of global car demand by 2030.

“One thing we remain highly [convinced of] is that the transition to an electrified economy [will] happen,” says Engine No. 1’s Horton.

“We’re hitting speed bumps and hurdles all over the place.…There will be more.”

It will be up to Ford and GM to navigate them.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario