Why Are Tech Stocks Down? Bond Yields Are Up

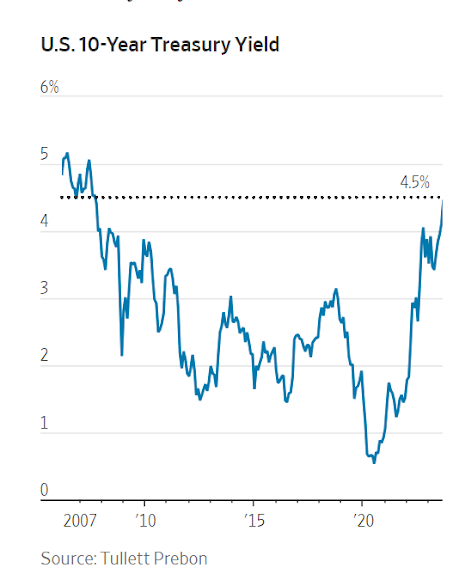

Relentless climb brings 10-year Treasury yield above 4.5%

By Sam Goldfarb and Eric Wallerstein

The summer slide in U.S. government bond prices has intensified since Labor Day, rattling some of the hottest parts of the stock market.

Many investors had hoped for some autumn relief to nearly two years of declines that have repeatedly pushed Treasury yields above Wall Street’s expectations.

Now, yields on 10-year notes—a key benchmark for borrowing costs on everything from mortgages to corporate loans—have hit 16-year highs above 4.5%.

At the same time, yields on shorter-term Treasurys have also jumped, with the two-year yield above 5.1%.

The bond-market ructions have jarred other markets.

Surging Treasury yields have punished stocks in a variety of ways, including reducing their appeal relative to bonds and increasing borrowing costs for companies.

Rising yields have hit tech stocks particularly hard, because those companies’ future profits are worth less relative to the risk-free returns from holding Treasurys to maturity.

Behemoths such as Amazon.com and Apple have slid 4.9% and 6.3% in September, respectively, after logging big gains earlier in the year.

The tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite is down 5.4%.

The major force behind the bond market moves?

A robust U.S. economy that continues to grow despite the Federal Reserve’s fastest interest-rate increases in decades.

The result is that some investors are betting that the Fed will leave rates high for years to come, either to keep fighting inflation or because it sees no pressing need to take them much lower.

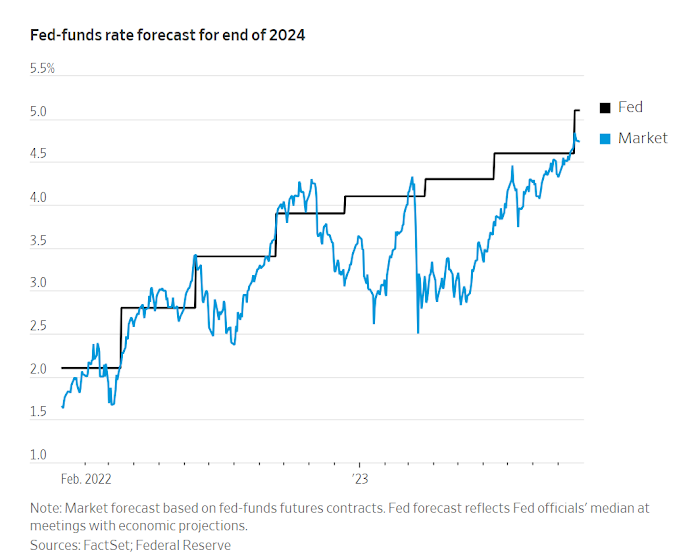

Heading into last week’s Fed meeting, investors thought that some officials would signal that they now anticipated fewer interest-rate cuts next year than they had before.

Yet those projections for year-end 2024 rates were even higher than expected, reflecting a broad shift among officials.

“The market is coming around to the fact that for the medium-to-long term, rates will be higher,” said Richard Chambers, global head of repo trading and co-head of short macro trading at Goldman Sachs.

Though the S&P 500 is still up 13% this year, it is down 9% since yields began rising in 2022. Stocks’ rally this year was largely halted when the 10-year yield reached 4% at the end of July.

Some analysts have also warned that stock valuations broadly look stretched when measured relative to the yield that investors can get on government bonds. Others have argued that those valuations will look more reasonable once bond yields start to fall.

But time has passed, and yields have only risen further.

Rising yields have hit technology stocks hard, with the tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite down 5.9% so far this month. PHOTO: BREANNA DENNEY/THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Rising yields have hit technology stocks hard, with the tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite down 5.9% so far this month. PHOTO: BREANNA DENNEY/THE WALL STREET JOURNALFor bond investors, higher yields mean more income going forward.

But that has come with a cost, as new bonds issued at higher rates cause prices to fall on older ones offering smaller coupons.

Through Friday, a widely tracked index of investment-grade bonds—comprising mostly Treasurys, government-backed mortgage securities and corporate debt—had lost 0.2% this year, counting interest payments and price changes.

That comes after it lost 13% last year and 1.5% in 2021, the first consecutive years of negative total returns since the index’s inception in the 1970s.

Many think yields may have finally reached their peak.

Fed officials’ latest projections show inflation declining to 2% by 2026 and gross domestic product falling between 1.5% to 2%.

Should the Fed’s forecasts prove prescient, “I’m not sure how much more yields can continue to rise,” said Subadra Rajappa, head of US Rates Strategy at Société Générale.

If yields remain lofty for an extended period, Rajappa expects something in the domestic or global economy “to break.”

Some investors, though, argue that supply and demand dynamics will keep yields elevated.

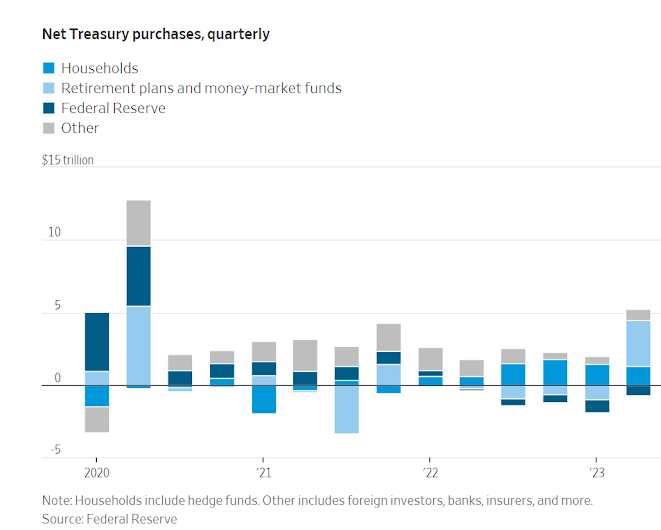

Treasury issuance has jumped recently, thanks to a growing federal budget deficit, even while the Fed steps back from purchases made to support the economy in recent years.

Households—a category comprising hedge funds and other private investors—money-market funds and retirement plans have stepped up to fill the gap. But that demand will be tested in the coming quarters and years.

“The marginal buyer of Treasurys is different, if not less,” said Jason Granet, chief investment officer of BNY Mellon.

“The Fed isn’t a buyer, banks historically are a fraction of buying and now the banking system is shrinking.

Put those together, Treasurys have to clear at a different price.

That means higher yields—it’s pretty simple.”

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario