A Big Chill Is Here for the Housing Market. Next Year Could Bring More Trouble.

Affordability is still an issue, mortgage rates will remain high, and homes are sitting on the market longer. It all adds up to a stalled 2023 for real estate.

Shaina Mishkin

Todd Clark and his wife, Jocelynn Wilde-Clark, have lived through the ups and downs of the housing market in the time of pandemic.

In the summer of 2021, as Covid produced frenzied home buying, the couple had to up their bid for a brick town house in Raleigh, N.C., by more than $20,000 over the $240,000 asking price to get the property.

“You had to blindly pick a house and go from there,” Clark recalls.

This past summer, Clark, 27, and Wilde-Clark, 26, decided that the town house was too cramped to start a family and ventured back into the market.

Homes were sitting on the market longer by then, and they didn’t encounter any bidding wars.

They bought a three-bedroom single-family house after negotiating a $22,000 discount.

The trade-off?

They had to knock $15,000 off the town house’s price to sell it, and their mortgage rate for the new home is nearly double their old rate.

“It’s crazy when you look at the numbers versus what it was a year ago,” Clark says.

What’s happening in Raleigh is happening in many cities.

The U.S. housing market has left its pandemic frenzy in the rearview mirror.

This year through mid-November, the 30-year mortgage has seen its largest percentage-point gain since 1972, the first full year that Freddie Mac FMCC 1.16% started collecting the data, according to Dow Jones Market Data.

The Federal Reserve’s fight against inflation means the days of sky-high bidding wars, low mortgage rates, and rapid home-price appreciation are gone.

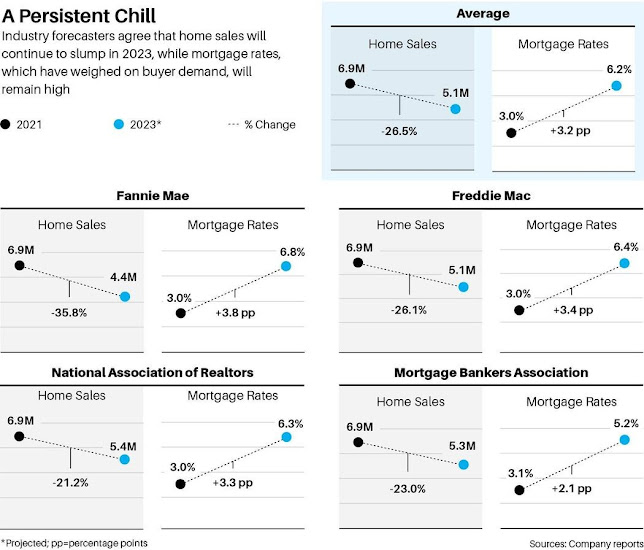

Home sales in the U.S. are projected to end the year at 5.8 million—a 16% slide from 2021’s multiyear high, according to the average estimate from four government data sources and housing trade groups.

The drop will continue into 2023, with home sales expected to slide a further 13%, to 5.1 million.

Fannie Mae FNMA 2.04%, which buys mortgages from loan originators, expects home prices to drop below year-ago levels next year, according to its most recent forecast.

In 2023, home prices tracked by its index will end 1.5% lower than the fourth quarter of this year, Fannie Mae estimates.

“If you sold or bought a home in the past couple of years, you are definitely going to be shocked about what the market looks like next spring,” says Derrick Thornton, a Raleigh-based real estate agent with Coldwell Banker Advantage.

Bidding wars, measured by online real estate broker Redfin RDFN 2.00% as the share of offers written by their agents that faced competition, fell in October to the slimmest share nationally since April 2020.

At the height of the hot pandemic housing market, about two in three offers faced competing bids.

The pullback has ripple effects for buyers, sellers, and the economy.

Last year’s ultralow 30-year mortgage rates—about 3% on average—mean that homeowners who locked in those rates are staying put rather than selling and jumping back into the market, where they now face average rates of 6.5%.

That contributed to October’s 16% year-over-year drop in new listings recorded by Realtor.com, keeping many buyers on the sidelines.

Prices from June to October declined at the greatest magnitude in a decade, but remain historically high.

Todd Clark and Jocelynn Wilde-Clark recently sold the townhouse they bought at the beginning of the pandemic and moved into a single-family home. . PHOTOGRAPH BY JEREMY M. LANGE FOR BARRON’S

Todd Clark and Jocelynn Wilde-Clark recently sold the townhouse they bought at the beginning of the pandemic and moved into a single-family home. . PHOTOGRAPH BY JEREMY M. LANGE FOR BARRON’SThe rise in rates and prices over the past year has priced about 15 million mortgage-ready home buyers out of the market, according to a recent Freddie Mac analysis—limiting their ability to build wealth through homeownership.

Home-price declines and sinking consumer sentiment could weigh on consumer spending, wrote Fannie Mae forecasters in mid-November.

“This will likely contribute to slower consumption growth because of a negative ‘wealth effect,’ in which households are less likely to dip into savings or take on more debt because they feel that their assets are declining in value,” they wrote.

Homeowners may be reluctant to tap their home equity for purchases like cars and appliances, which will cause a drag on spending, says Susan Wachter, professor of real estate at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

And lower housing demand already has translated into job losses in real estate–related industries such as mortgage banking.

It isn’t all bleak.

Less demand means housing’s contribution to the consumer price index—it constitutes 40% of core CPI—could ease inflationary pressure.

“We may by spring see a significant decrease in inflation, which at least would have the effect of slowing down the inexorable rate rises,” Wachter says.

Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell on Wednesday said the central bank may moderate its rate increases in December.

Coldwell’s Thornton says that he offers clients a checklist to help them prepare for a sale.

For the past two years, he says, it was largely ignored because homes were a hot commodity.

“It didn’t matter if it had any smells,” he says.

“Nothing mattered as far as the condition of the home.”

A real estate agent shows prospective buyers a town house in Raleigh. . PHOTOGRAPH BY JEREMY M. LANGE FOR BARRON’S

A real estate agent shows prospective buyers a town house in Raleigh. . PHOTOGRAPH BY JEREMY M. LANGE FOR BARRON’SThe tide has now turned, and sellers need to do something unthinkable just six months ago: make an effort to market their homes.

“Now, we really need to treat your home like you’re in a retail store,” Thornton says.

The sentiment is far from unique to Raleigh.

“Sellers are concerned if their house is not flying off the market,” says Kristin Sanchez, a Redfin agent in Nashville, adding that “even though, before the pandemic, it was not unusual for a house to sit on the market for 30, 60, or even 90 days.”

The median home in October spent 51 days on the market, a six-day increase compared with the same month last year, but less than the longer-term average of about 63 days, according to Realtor.com, which has tracked the data since 2016. (Barron’s and the company that operates Realtor.com are both owned by News Corp.)

Raleigh got caught up in the pandemic rush to buy real estate.

Housing supply dwindled, bidding wars erupted, and prices rose more than 50% in the two years since the start of the pandemic, according to the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

This metropolitan area of 1.4 million is attractive: Its downtown is filled with shops, restaurants, and nightclubs.

Raleigh, along with Durham and Chapel Hill, make up the so-called Research Triangle, home to a slew of universities and high-tech companies.

IBM and Pfizer are among the large employers.

That is a big reason for the Raleigh area’s popularity among out-of-state movers.

Nearly half of all views to Raleigh-area home listings on Realtor.com came from other states in the third quarter, according to the website.

But Raleigh hasn’t avoided the broader market cool-down.

Median home-sale prices in Wake County, where Raleigh is located, were up 20.3% year over year in October 2021, and slowed to 13% this past October, according to Triangle MLS, a regional multiple listing service.

Industry forecasters broadly expect that home-price growth, which has already slowed, will cool further in 2023.

The National Association of Realtors expects existing-home prices nationally to rise 1% in 2023, while Freddie Mac expects prices gauged by its housing market index to dip slightly.

CoreLogic, a housing data provider, sees home-price gains slowing to 3.9% nationally by next September, according to its most recent home-price index report.

Some metro areas will see price drops.

Of the 30 metros that CoreLogic estimates are at the greatest risk of price declines over 10%, those in Florida, Washington, and Oregon appear most frequently.

Zillow Z 0.94%, the home-listings website, expects a broad slowdown in home value growth by next October, with mild declines in some metropolitan areas.

Of the 10 largest metropolitan areas, Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago are expected to see the greatest year-over-year dip, according to projections through October 2023.

The Raleigh metro area got caught up in the pandemic rush to buy real estate, but it hasn’t avoided the broader market cool-down. . PHOTOGRAPH BY JEREMY M. LANGE FOR BARRON’S

The Raleigh metro area got caught up in the pandemic rush to buy real estate, but it hasn’t avoided the broader market cool-down. . PHOTOGRAPH BY JEREMY M. LANGE FOR BARRON’SMark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, says that metropolitan areas where home prices ran up most dramatically during the pandemic are among those susceptible to the greatest pullback.

Investor demand, remote-work dynamics, and underlying economic strength will also affect how well local economies hold up, he adds.

Price drops will be most pronounced at the higher end of the market, while home prices will hold up best among lower and midprice homes, where supply is most constrained, he says.

“The higher part of the market doesn’t have the same kind of shortages—and some markets maybe are a little oversupplied,” Zandi says.

Of the nation’s 50 largest metropolitan areas, Moody’s Analytics projects prices to fall most from the fourth quarters of 2022 to 2023 in Nashville, Phoenix, and Austin, Texas.

Boise, a smaller metro that Barron’s reported in September 2021 was a growing midtier city with a perfect storm of high demand and low supply even before the pandemic, could also see substantial declines.

Even if rates retreat, home sales are unlikely to return to their frothy pandemic pace.

Affordability will continue to be a problem for the average buyer in 2023.

“We think that people are kind of underappreciating, or glossing over, the severity of the affordability crisis right now,” says RBC Capital Markets analyst Mike Dahl.

For the average home buyer in late 2022, it’s a cost problem: Higher rates and prices have increased the monthly payment on a median home by about 70% since February 2020, according to Redfin. Sales have thinned by nearly 30% from a year earlier.

Todd Clark and Jocelynn Wilde-Clark’s new single-family home in Raleigh. PHOTOGRAPH BY JEREMY M. LANGE FOR BARRON’S

Todd Clark and Jocelynn Wilde-Clark’s new single-family home in Raleigh. PHOTOGRAPH BY JEREMY M. LANGE FOR BARRON’SHigher mortgage rates continue to weigh on affordability. In 2021 and early 2022, historically low rates enabled a surge of home sales, as bidding wars over a short supply sent prices skyward at the fastest clip on record.

Those low rates were largely due to Fed monetary policy, which loosened during the pandemic’s early days to protect the economy.

The sharp ascent in mortgage rates began when the central bank raised key interest rates by 0.75 percentage point in June—the largest rate hike since 1994.

Homeowners now have less financial incentive to let go of their low mortgage rates.

The number of homeowners who could benefit from refinancing has shrunk significantly.

Even if rates descend to 5%, only about 2.7% of the approximately 53.5 million first-lien borrowers would have financial incentive to refinance, according to mortgage analytics company Black Knight BKI -0.90%.

Homeowners staying put will contribute to a slow spring season—but it could also minimize the impact on prices.

“You might see that limited inventory hopefully puts some damper on the magnitude of price declines,” says RBC’s Dahl, who says he expects existing-home prices to fall 4% next year.

In Austin, where there are 13% fewer new listings than last year, those who are selling “are going through life changes or situations where they have to sell, not just a move-up,” said Andrew Vallejo, a Redfin agent in Austin.

Some homeowners may have the luxury of sitting out the housing-market recession—but the same can’t be said for developers.

“Builders are in the business of selling homes, and they have to actually move through some inventory,” says Dahl.

Those sales will come at a cost, as companies are offering incentives to entice potential buyers.

Already, 59% of builders responding to a November National Association of Home Builders survey said they have offered perks such as paying points, mortgage rate buydowns, and price cuts to attract buyers.

Builders’ share prices could come out of the doldrums once sales declines narrow.

So far, incentives haven’t had a “significant impact on the ability to stabilize or improve sales pace,” Dahl says.

But investors are waiting for the right moment to start bargain hunting.

“We talk to many [institutional investors] who are still negative on housing and home-building stocks,” says Carl Reichardt, home-building analyst at BTIG.

“But many are doing their homework on the housing market because they believe housing leads to broader changes in the economy, and therefore believe housing might be among the first to bounce back.”

The housing pullback could lure investors looking for bargains back into the market.

“As an investor in single-family rentals, it does give us an opportunity to get new inventory at scale, potentially from builders,” says Carly Tripp, Nuveen Real Estate’s global chief investment officer.

Individual buyers could find lower rates at local banks and credit unions, says Nick Gelfand, president of the Western Massachusetts–based NRG Real Estate Services.

“Their products are more tailored toward specifically the local market,” he says.

“They’re not looking to bundle these loans and sell it.”

Take Clark, the Raleigh homeowner.

He says that he and his wife worked with a local bank, where they had an established history, for a lower-than-expected rate.

They toured four “reasonably priced” houses and ultimately had their under-asking offer accepted.

“I didn’t expect it to be as good of a time to buy as it was,” Clark says.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario