Federal Reserve’s Portfolio Runoff Has Begun

Central bank is allowing securities to exit from its $8.9 trillion portfolio by not reinvesting the proceeds when they mature

By Nick Timiraos

The Federal Reserve pumped money into the U.S. economy starting in March 2020 to stabilize markets at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. / PHOTO: JOSHUA ROBERTS/BLOOMBERG NEWS

The Federal Reserve pumped money into the U.S. economy starting in March 2020 to stabilize markets at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic. / PHOTO: JOSHUA ROBERTS/BLOOMBERG NEWSThe Federal Reserve began the process Wednesday of shrinking its $8.9 trillion asset portfolio.

Here are answers to five of the most commonly asked questions from our readers about how it works.

Q: When the Fed shrinks its asset portfolio, is it selling bonds?

No.

The Fed dramatically expanded its portfolio in March 2020 to stabilize dysfunctional markets, and then it continued to purchase Treasury and mortgage-backed securities in large quantities after that to provide additional stimulus to the economy by holding down longer-term yields.

It ended those purchases in March 2022 and has been keeping its holdings steady since then by reinvesting the proceeds of maturing securities into new ones.

Starting June 1, the Fed will allow up to $30 billion in Treasurys and $17.5 billion in mortgage bonds to mature every month without investing the proceeds.

The central bank is shrinking its holdings passively, or by attrition.

(Because none of the Fed’s Treasury holdings mature until June 15, this process for Treasurys doesn’t actually take effect for two more weeks).

In September, the Fed will allow twice as many securities—$60 billion in Treasurys and $35 billion in mortgage bonds—to run off its portfolio.

This design is similar to how the Fed allowed its holdings to shrink between October 2017 and July 2019, though the amounts of securities that are running off the Fed’s holdings are larger now than they were then.

Q: But what about mortgage securities?

Some Fed officials have said those could be actively sold at some point.

Why is this under consideration?

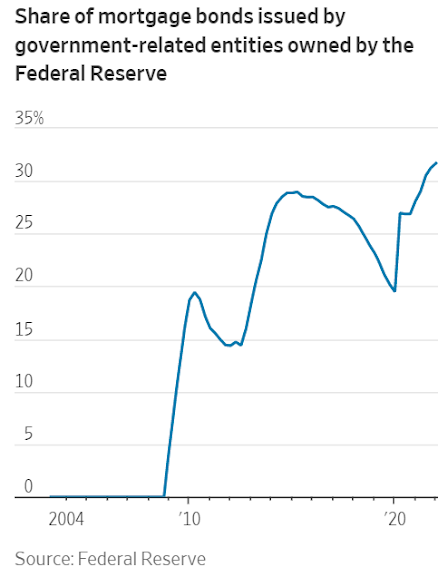

The Fed has said that over the long run, it wants to own primarily Treasury securities. Selling mortgage assets would more quickly shift the composition of its asset holdings toward Treasurys.

The Fed didn’t actively sell mortgage bonds last decade, but it never ruled out such sales.

And it hasn’t ruled out sales of its $2.7 trillion in mortgage-backed securities at some point down the road this decade, because it will take a long time to shrink those holdings passively.

The 30-year mortgage rate has increased by more than 2 percentage points over the past six months, which will lead to much lower refinancing volumes and therefore fewer early paydowns of such long-term securities in the coming years.

The upshot is that even though the Fed will allow up to $35 billion in mortgages to run off its portfolio by September, in most months, the Fed might see less than $20 billion in securities decline through passive runoff.

Officials haven’t decided whether or when to sell securities, and minutes from the Fed’s recent policy meetings haven’t provided many clues about the debate inside the central bank’s rate-setting committee.

Because mortgage rates have increased substantially, officials will have to weigh the economic effects of any such sales. At current interest rates, the Fed is also likely to sell those assets at a loss.

Q: What does the Fed do with the money it receives from the payment of principal on its holdings?

The Fed essentially created money out of thin air to buy the bonds.

Now, it will destroy the money in the same way.

When private investors buy bonds, they use cash, borrow funds or sell assets to raise the money to make that purchase.

The Fed is different. It doesn’t have to do any of those things because it can electronically credit money to the accounts of bond dealers who sell mortgage-backed securities or Treasurys.

When the Fed purchases a security, it creates a bank deposit known as a reserve that shows up in the account of the seller.

When the process is reversed, instead of reinvesting the proceeds of maturing bonds, the Fed erases them electronically.

It doesn’t print currency to purchase the bonds, and so it won’t be destroying any paper currency.

The electronic money essentially vanishes from the financial system.

The New York Fed provides a detailed breakdown of the accounting on its Liberty Street Economics blog.

Q: What effect does this have on the economy?

There is no consensus on the effects of the Fed’s asset purchases, sometimes called quantitative easing, and the portfolio runoff, sometimes called quantitative tightening.

Several analysts have suggested that the runoff could be equivalent to one or two quarter-percentage point increases in its benchmark short-term interest rate.

In theory, the Fed’s purchases should reduce long-term yields by pushing down the so-called term premium, or the extra yield that investors receive for holding longer-dated assets.

Analysts at JPMorgan Chase & Co. have estimated that each $1 trillion in Fed bond purchases during and after the 2008 financial crisis reduced the term premium on a 10-year Treasury note by 0.15 to 0.2 percentage point.

Runoff should boost the term premium by increasing the supply of bonds that private investors must now absorb, pushing their prices down and raising bond yields, which move in an inverse relationship to prices.

Treasury debt issuance decisions also matter.

In late 2018, some investors grew concerned about the effects of the Fed’s portfolio runoff, but back then, the amount of debt being issued by the Treasury was increasing sharply as tax revenues declined following tax cuts approved by then-President Donald Trump.

Right now, tax revenues are surging, which could require the Treasury to issue less debt than would otherwise be the case.

Q: When will the Fed stop its portfolio runoff?

The end date isn’t clear.

In 2019, the Fed slowed its runoff program much sooner than most officials had initially anticipated, and halted the runoff in July 2019, when the Fed cut interest rates amid concerns over an economic slowdown.

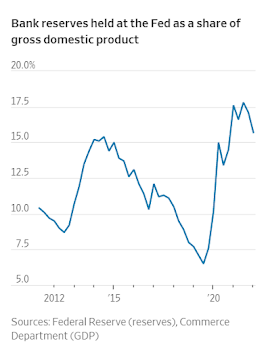

In September 2019, turmoil in overnight lending markets led officials to conclude that they had drained too many reserves from the financial system, leading them to make a U-turn and increase the portfolio for several months.

That fine-tuning was mooted by the aggressive response to the Covid-19 pandemic in March 2020.

In a February speech, Fed governor Christopher Waller said he thought reserves as a share of gross domestic product—around $3.8 trillion or 16% of GDP at the end of March—could potentially decline to levels seen in early 2019, when they were around 8% of GDP.

Projections released last month by the New York Fed suggested that this might be consistent with allowing Treasury and mortgage holdings to decline to around $6 trillion in mid-2025.

The economy’s performance will also shape the endgame.

The Fed could halt the runoff sooner if, for example, officials switch from raising rates to cutting rates in the next few years.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario