Ukraine and the Global Economy

Some trends have become apparent now that details of the sanctions have come to light.

By Antonia Colibasanu

U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken recently met with EU foreign ministers to discuss the possibility of imposing additional sanctions on Russia for its invasion of Ukraine.

But though most countries around the world condemn Russian actions, some disagree on the timing of new sanctions until they can assess the damage they may cause their own economies.

After all, because economies are so interconnected, and because the current sanctions are so severe, it’s difficult to understand the full scope of their consequences.

First, there are trade sanctions that curb internal Russian development.

The ban on exports of specific technology and equipment for the Russian energy sector, for example, effectively disables Russia’s ability to upgrade its oil refineries.

It also limits Russian access to cutting-edge technology.

An immediate ban was put on all sales of aircraft, aircraft parts and equipment for Russian airlines.

Then there are financial sanctions.

The structure of the SWIFT ban was specifically designed to avoid interrupting payment for Russian hydrocarbon exports to Europe.

The ban currently targets about 70 percent of the Russian banking market and, along with the restrictions imposed on Russian international reserves, is meant to increase Russia’s borrowing costs and thus accelerate inflation.

And since Canada, Japan, Australia, Taiwan and Singapore have since joined the U.S. and the EU on these sanctions, nearly the entire global financial system is abiding by them.

In practice, this means the majority of banks around the world will drop clients if there is even a hint of ties to Russia.

Of course, global banks have invested billions of dollars in sanctions compliance programs over the years – but never before have the sanctions been so complex: Their targets are multiple wealthy Russian elites, some major Russian banks and state entities and their subsidiaries.

As a result, banks – even those in countries that have not imposed sanctions but work with banks in countries that have imposed sanctions – are practicing extreme caution.

This could slow down all banking processes in general and thus aggravate existing global trade disruptions.

In fact, the sanctions have added an operational uncertainty to the already high fears attached to the war in Ukraine, as evidenced in global financial markets.

Energy

Energy, of course, is at the forefront of nearly everyone’s minds.

Just after Russia invaded, Germany announced that the Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline had been terminated.

But the SWIFT restrictions exempted payments for energy supplies.

Natural gas kept flowing at normal volumes through Nord Stream 1 and other pipelines.

Then on March 3, the Gascade pipeline operator announced that natural gas flows stopped from Russia to Germany via the Yamal pipeline.

Europe has some options for offsetting the loss of Russian energy.

Germany, the biggest consumer of Russian energy, could turn to Norway, the Netherlands and the U.K. Southern Europe can receive gas from Azerbaijan via the Trans Adriatic Pipeline to Italy and the Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline through Turkey.

American and Qatari liquified natural gas can be supplied through the Baltic and the Mediterranean terminals.

Even so, fully replacing 150 billion-190 billion cubic meters a year of Russian gas to the EU is not achievable in the short term.

(It should be said that a third of Russian gas could be replaced by other sources if the EU was serious about it.)

Though these measures are clearly meant to hurt Russia, they could backfire if Moscow retaliates by cutting supplies altogether.

But this is unlikely to happen.

Russia simply can’t afford to give up its biggest source of money right now.

And for all the talk of Russia turning to Asia, supplying that market is easier said than done.

Moscow would have to build new infrastructure and alter the current extraction facilities to meet Asian/Chinese energy standards.

All of which would translate into years of work and investment in a geography that isn’t particularly well suited to such projects.

Russia will, however, continue to supply China with its coal, the price of which, like oil, has reached record highs.

While the sanctions have also excluded coal exports, buyers from Europe, Japan, South Korea and China are nonetheless worried about Russia’s ability to deliver and their exposure and difficulty in working around the sanctions.

This is why China, which gets 15 percent of all its coal from Russia, is reportedly scaling back orders.

Russia and China will no doubt find a way to make it work eventually, but that doesn’t help the short-term pressure on energy markets.

Shipping

Relatedly, energy shipping has also taken a hit.

Russia’s major state-controlled shipping company the SCF Group, along with other “owned and controlled” shipping companies, was put under Western sanctions as well.

Three SCF tankers had to return home after the U.K. and Canada refused to give them entry to their ports.

The SCF has a live fleet of 133 vessels, including 108 tankers and 14 gas carriers, that are self-owned, the majority serving the energy business.

It also has more than 30 ships still under construction, the majority of which are LNG carriers serving Arctic projects. (Diesel is also shipped by sea.)

The shipping industry is scrambling to recalibrate.

While ships are diverted and tankers are delayed, there are also fewer loadings.

And some are unclear how much shipping is under sanctions.

The SCF tankers that were rejected by the U.K. and Canada, for example, had been ordered prior to the imposition of sanctions.

Issues like these have forced ports and shipping operators to do their own due diligence on the matter.

Many ship owners and shipping operators are revisiting their contracts with Russian companies and are investigating the ownership structure of their partners to make sure they are complying with sanctions.

Things are a little better for container shipping, where Russia accounts for only less than 3 percent of the industry globally.

Self-sanctioning is particularly affecting this sector.

Leading container shipping and logistics firm Maersk has suspended almost all cargo shipping to and from Russia and Belarus with the exception of food, medicines and humanitarian supplies.

The company also warned of delays due to extensive screening in ports and customs.

Self-sanctioning and operational delays will continue until there is more clarity on the specifics of sanctions.

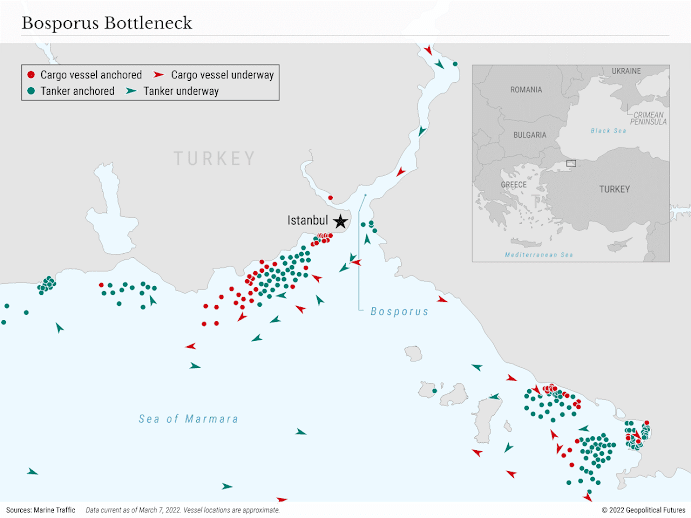

The waters south of Ukraine are no longer operational, and the Bosporus is particularly crowded, making the Black Sea a risky place to be.

This will cause insurance companies to add war risk premiums for all shipments in the area, increasing the transportation price for goods coming into and out of the region.

Agriculture

Agricultural trade is already affected by the problems in the shipping industry.

Ukraine and Russia are both major exporters of grains.

According to industry reports, the war has already cut into corn exports, with less than 20 million-25 million tons having been shipped to markets this year already.

If the conflict continues, it may also affect barley exports, which begin in June-July.

Notably, estimates from various industry reports on grain trade fail to take into account the medium- to long-term effects of war in Ukraine.

They refer only to the foodstuffs in storage and the foodstuffs ready to be shipped.

No one can give an estimate on Ukraine’s production levels this year.

As things stand now, it all depends on the number of days that the conflict continues.

Even more problematic is that even before the war, 2022 hasn’t been a good year for agriculture production in general.

Droughts in both hemispheres have negatively affected grain crops already.

High energy prices will probably lead to higher fertilizer prices.

All this will drive an increase in food prices at a time when global inflation is already high.

Metals

Finally, the global industry is also influenced by the price and availability of other commodities produced and sold by Russia on the world market: aluminum, cobalt, copper, nickel, palladium, platinum and steel, to name just a few.

Sanctions imposed so far haven’t directly targeted these metals, but that could change if Moscow retaliates against the sanctions or escalates the war.

The uncertainty surrounding it, though, has caused commodity buyers to pull back from trading with Russian producers, according to reports citing trade flow monitoring services.

More important, the SWIFT sanctions make it hard for financial institutions to support their clients who do business with Russia.

In Europe, Societe Generale and Credit Suisse Group reportedly stopped financing commodities trading from Russia, while China’s largest state-owned lenders are restricting financing for purchases of Russian commodities.

Though these reports are unconfirmed, the market has responded as though they are true.

Increased commodities prices have made basically everything more expensive.

This is particularly true with regard to aluminum and copper.

Aluminum is used for all industrial energy infrastructure and all machinery, from kitchen appliances to automobiles, and its price is very sensitive to energy prices because its production is energy intensive.

Copper is used in electrical cables and engines.

So even if you have lots of aluminum but you don’t have the very small piece of copper ensuring electrical transmission, you can’t use the machinery you need to produce certain products.

More broadly, the war in Ukraine and the sanctions it triggered could have two lasting macroeconomic effects.

The first is that it may accelerate Europe’s efforts to find alternative sources of energy.

The second is that it may hasten, or even aggravate, a global recession and the restructuring of the global economy.

This is all subject to change, of course, since war creates economic uncertainty.

But it’s safe to say things may get worse before they get better.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario