When Will Shortages End? Here’s Why Forecasts Are Often Wrong

Bottlenecks could finally be starting to ease, but investors should remember that individual companies tend to underestimate the scope of global supply-chain problems

By Jon Sindreu

Bottlenecks have been concentrated higher up supply chains, where they do most damage. / PHOTO: APU GOMES/AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE/GETTY IMAGES

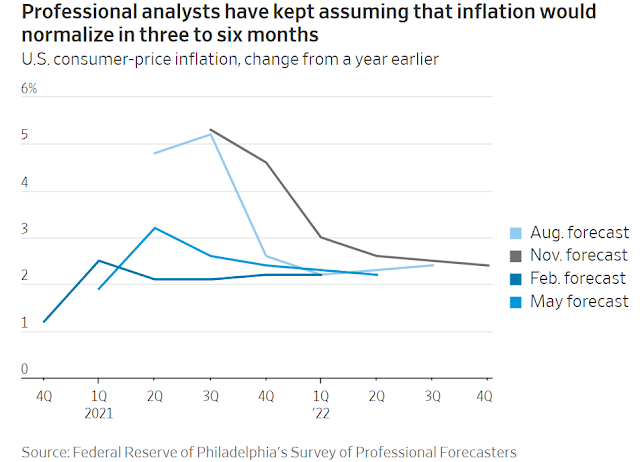

Bottlenecks have been concentrated higher up supply chains, where they do most damage. / PHOTO: APU GOMES/AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE/GETTY IMAGESNot for the first time this year, analysts are optimistic that supply shortages are easing and will be fixed within three to six months.

There is reason to be skeptical of this figure—even without cheering for tighter monetary policy.

Delivery times for firms ordering supplies have stopped getting longer, according to purchasing managers’ surveys in the U.S. and Europe released this week.

Global shipping rates seem to have peaked, and Asian factories are reopening.

Some retailers say they are already well-stocked ahead of the Christmas season.

These are all good signs, and help explain why many companies think the logjam that has pushed inflation up across the world this year may come unstuck in the next quarter or two. But such forecasts have proved wrong before.

With so much at stake, it is worth asking why.

Some investors believe analysts have underestimated consumer demand—an argument that would align with the case for central banks to raise rates immediately.

But Kallum Pickering, senior economist at Berenberg Bank in London, offers a better explanation.

Over the past year he has often asked analysts and companies to draw supply chains, identify the pressure points and estimate how long it would take to fix them.

Their answer was typically six months, based on historical experience.

Yet this raises a problem.

“What individual companies see as their supply chain is actually just one strand in a global supply web that links many other firms to the same producers and distributors.

You can’t just average out the timings they are giving you,” he said.

The point echoes John Maynard Keynes’s “paradox of thrift,” in which attempts by individuals to save more depresses income for the economy overall.

When firms tell analysts they are spending resources to fix supply-chain issues, they don’t take into account efforts by other firms to apply pressure on the same suppliers on a similar expected timeline.

Another problem is that firms at each point of the web likely respond by engaging in precautionary hoarding—the “bullwhip effect.”

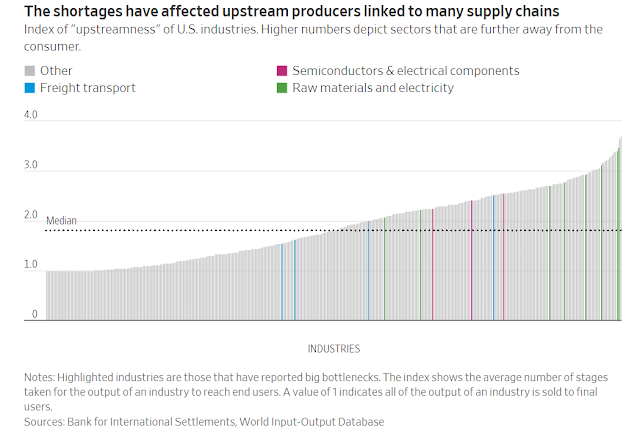

Indeed, the bottlenecks have been concentrated higher up supply chains, where they do most damage.

In a recent report, the Bank for International Settlements found that the output of U.S. industries currently affected by shortages goes through a median 2.5 further production stages before reaching consumers, compared with 1.8 for the rest.

Commodity extraction ranks high on this scale, as does assembly of printed circuit boards, which typically include microchips.

The ripple effect of these products on overall output is often twice as large, the BIS estimates.

Of course, demand has played a role too: It has been skewed toward goods because of the pandemic, perpetuating shortages even as production recovered to 2019 levels.

Delays were also compounded by unexpected events, such as wildfires in the U.S., low wind speeds in Europe, a fire at a Japanese semiconductor plant and a drought in Taiwan.

Eventually, the rebalancing of demand toward services, the unwinding of the bullwhip effect and investments in shipping and production capacity will likely push prices down again.

But, in a world of globalized supply chains, anticipating the timing of this reversal may be next to impossible.

Even if high inflation persists beyond today’s projected timelines, investors and central bankers shouldn’t necessarily assume the broader economy is overheating.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario