Capital for the people — an idea whose time has come

California’s experiments with ‘pre-distribution’ could be attempted at the federal level

Rana Foroohar

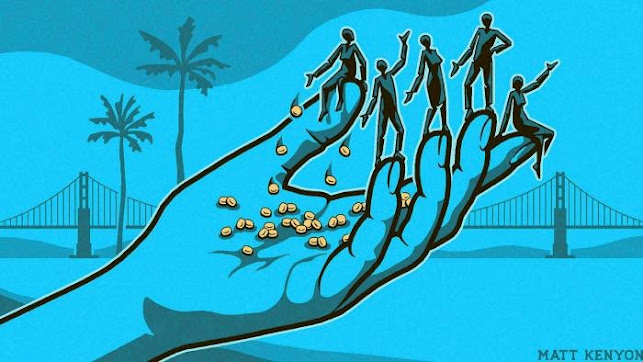

© Matt KenyonIf American states are, as former US Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis once put it, the “laboratories of democracy,” then it’s worth watching closely what’s happening in California right now.

The threat of rising taxes and a “soak the rich” political atmosphere has led some wealthy Golden State residents, including a number of technology entrepreneurs, to leave for cheaper pastures such as Austin or Miami.

This has, in turn, prompted worries of a larger migration that would have an impact not only on the state’s tax base, but on the growth and innovation that have made California the world’s fifth-largest economy.

It is an exceptionally fraught situation.

While nobody these days has much sympathy for wealthy individuals or companies (witness the recent justified fury about the ProPublica leaks showing how little tax the wealthiest Americans pay), or really believes in trickle-down economics, the threat of tax and regulatory arbitrage by other states is real.

The good news is that California is applying some typically creative thinking to the problem.

What if there was another way to harness company and citizen wealth for the benefit of all?

One such idea gaining popularity is what has been called “pre-distribution.”

Unlike traditional methods of redistribution, in which the state taxes existing wealth and then uses it to bolster various projects and constituents, pre-distribution is all about harnessing capital the same way investors do, and then using the proceeds of the capital growth (which as we know far outpaces income growth) to fund the public sector.

The idea of allowing more people to become owners of capital has actually been in operation for some time.

The CalSavers programme, created in 2016, allows for individuals such as gig workers or independent contractors who do not have access to private sector retirement accounts to contribute to professionally managed funds in a system run by the state.

Likewise, Proposition 24, the California Privacy Rights Act, was passed last year and will go into effect in 2023.

This actually creates a kind of stealth sovereign wealth fund, in which 93 cents of every dollar garnered by the fees paid by companies for violations of privacy (which, given the nature of surveillance capitalism, are likely to be substantial) can be invested by the Treasury, and the proceeds of any gains used to pay for government operations.

“It’s a way of helping us not have to raise taxes,” says California Senate majority leader Robert Hertzberg, a Democrat.

He, along with some very rich Californians like former Google chief executive Eric Schmidt and Snap founder Evan Spiegel, have proposed that the concept be broadened into something called “universal basic capital”.

The idea is that seed contributions of equity from companies or philanthropists could be invested into a fund that would then be used by individual Californians for things like retirement security, healthcare and so on.

Already, in the 2021-2022 budget, Gavin Newsom, the governor of California, has proposed using some of the state’s tax surplus this year — which along with federal Covid relief has put an extra $100m into public coffers — to start college accounts for every low-income first grader in the state.

One can imagine going further and having the state take a small equity position, perhaps 3-5 per cent, in start-ups, as countries like Israel or Finland already do.

Given that the current value of publicly traded companies in California is roughly $13tn, that’s not chump change.

If the state had been able to take even a small stake in top firms a few decades ago, there might be far less of the “Occupy” Silicon Valley vibe in California right now.

Pre-distribution should not, in my view, be a substitute for taxation.

It couldn’t fill the gap, and taxes are in any case a way of bolstering a sense of civic duty and belonging.

But it should be seen as a new revenue stream particularly well suited to an age in which network effects and intangible assets are concentrating wealth not only in fewer hands, but in fewer businesses that can generate outsize gains with far fewer employees.

It could also help better align public and private incentives and rewards.

The massive wealth accrued by leading companies is in part down to the strength of the public commons — good schools, decent infrastructure, basic research, and so on.

As economists like Mariana Mazzucato frequently note, why should taxpayers pick up the bill for, say, laying high speed fibre without getting any of the commercial upside?

Indeed, if pre-distribution works in the laboratory of California, I expect it will be adopted in some way at the federal level.

The Obama administration actually tried to implement its own version of the CalSavers programme for the country as a whole, called myRA, but it failed in part because the funds were invested only in super safe low yielding Treasury bills at a time when the market as a whole was rising far faster.

Even at this politically polarised moment, it’s an idea whose time may have come.

Pre-distribution is supported by such unlikely bedfellows as hedge funder Ray Dalio and leftwing economist Joseph Stiglitz.

Perhaps that’s because while it doesn’t fundamentally alter the market system, it does broaden share ownership: a mix of capitalism and socialism that is right for our time.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario