The Pandemic’s Legacy of Financial Frailty in Emerging Markets

Critics of public debt accumulation usually mean well, but in many cases the alternative is steeper borrowing by individuals and companies

By Mike Bird

South Korea is an economy that had more room to provide fiscal support./ PHOTO: AHN YOUNG-JOON/ASSOCIATED PRESS

South Korea is an economy that had more room to provide fiscal support./ PHOTO: AHN YOUNG-JOON/ASSOCIATED PRESSDebt levels rose in almost every corner of the world last year, but how the burden is shared between governments and the private sector varies widely.

Some countries may come to wish the mix of borrowers was a little different.

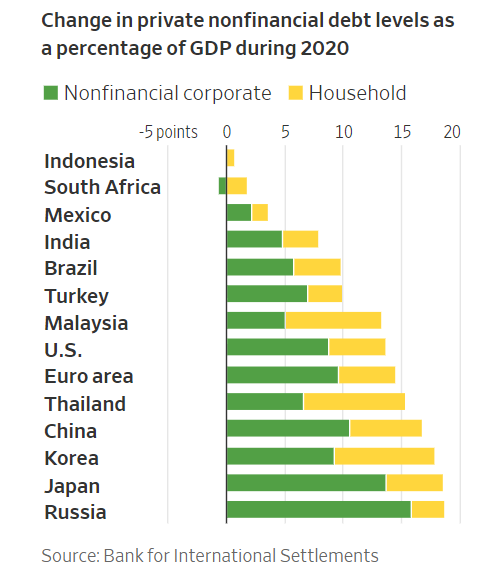

In several economies classified as emerging markets—notably Thailand, China, Malaysia, South Korea and Russia—the increase in private nonfinancial debt to gross domestic product ran to more than 10 percentage points in 2020, according to figures released by the Bank for International Settlements Monday.

In some, a sharper fall in GDP is doing more of the work in shifting that ratio, but the outcome is the same: more private debt relative to economic output.

Emerging markets have typically seen more limited increases in government debt than their developed counterparts.

Most countries aren’t in the position of the U.S., U.K. or Japan, which are able to expand state spending rapidly without worrying about undermining the value of their currencies and creating inflationary pressures.

In some cases, governments could have taken on more debt, but chose not to.

Based on last year’s evidence, though, the inability or unwillingness of states to borrow and spend may have resulted in a more precarious financial position for their private sectors.

During a major economic shock such as the pandemic, avoiding a large recession requires some sector or other having to borrow large amounts of money.

Of course, government borrowing isn’t a substitute for private borrowing.

In most advanced economies, the U.S. included, private debt has risen in the past year.

But lower government borrowing will lead either to higher private borrowing or a bigger economic shortfall.

South Korea is perhaps the most obvious case of an economy that had more room to provide fiscal support.

The government has expressed pride in the fact that its debt load rose so little last year:

The BIS numbers show an increase of just 4.5 percentage points relative to GDP, far less than in most economies.

But South Korea is at the higher end of the international spectrum when it comes to both nonfinancial corporate and household debt, which rose by 9.2 and 8.6 percentage points respectively in 2020.

Accumulations of private debt are typically a much greater financial risk to economies than larger government deficits.

Corporate debt has risen in particular among riskier firms over the past decade, with lower interest coverage ratios.

Any rise in debt-servicing costs could cause widespread distress.

Private borrowing also doesn’t do much for growth.

Research published by the Asian Development Bank in 2018 looked at the effect of corporate and household debt buildups on economic growth, and found similar results to studies for advanced economies: Some increases raise economic growth in the short run, but then growth tends to fall over the following one to three years.

Critics of public debt accumulation usually mean well, but in many cases the alternative to steeper borrowing by governments is steeper borrowing by individuals and companies.

Some emerging markets had little choice in their response when the pandemic began last year.

But others may wish that they had let government borrowing capacity take a bit more of the strain.

Private debt could prove to be a bigger problem in the long run.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario