Notes from a Changing City

China Tightens Its Grip on Hong Kong

Beijing is expanding its authoritarian influence ever deeper into Hong Kong. Many in the city have been arrested, while others are leaving - or going underground. Hopes for a degree of autonomy for the city have been dashed.

By Bernhard Zand, in Hong Kong

Hong Kong is one of the most vibrant cities in the world. Will it stay that way?Foto: Vincent Yu/ AP

Hong Kong is one of the most vibrant cities in the world. Will it stay that way?Foto: Vincent Yu/ APIt would be hard to find a place where the old world so suddenly gives way to the new as in the village of Liu Pok.

It is located just an hour's drive north of the famous Hong Kong skyline: three dozen houses packed close together, with a temple and a large banyan tree in the center.

A hill rises behind the village, with the other side of the settlement sloping down to the banks of a river.

It is quiet out here, with just the birds chirping and a young man practicing his basketball moves. But as you walk down to the river, a deep rumbling grows louder and louder.

The path leads through the brush past fishponds and overgrown graves.

Down below, though, the path opens up to an impressive panorama: A huge wall of skyscrapers stretching to the horizon and emanating a roar reminiscent of the machine-room of a container ship. Across the water lies China.

For the last 120 years, the Sham Chun River has formed the border between the former colony of Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland.

In the mid-19th century, the British defeated the Chinese empire and annexed first the city of Hong Kong and then the entire Kowloon Peninsula.

In 1898, the British signed a lease with China extending its holdings to the Sham Chun, thus significantly expanding the territory.

When that deal expired in 1997, Britain handed Hong Kong back to China.

By then, the subtropical British outpost had transformed into a metropolis of 6 million people, one of the most densely populated, wealthiest and most fascinating cities in the world.

With a population of 90 percent Chinese under British rule, the city had become a global focal point of trade and finance, a hub of shipping and air travel, a place packed with industry and cultural offerings that boasted a booming film industry.

A metropolitan center that radiated far beyond its city limits.

That attraction was always strongest in China. Tens of thousands migrated across the Sham Chun River in some years, initially fleeing poverty, hunger and war, but later escaping the Communist Party.

These days, Hong Kong is home to 7.5 million people, and many of them want to get out.

Finding them isn't hard.

"I don't think we're going to stay," says Jeremy, the 17-year-old shooting baskets on a court in Liu Pok on this morning.

"My grandfather was persecuted by the communists over there.

My father moved to Hong Kong.

Now, he wants us to emigrate to Australia."

Hong Kong was never truly democratic, not even under the British.

But it was run by the rule of law.

The certainty of never having to fear a nighttime visit from the state security authorities attracted millions to the city.

In mainland China, Hong Kong stood for the promise that many people pursued elsewhere during the 20th century as well: security, prosperity and freedom.

Despite its colonial history, the city held out all the promises of the West.

But Beijing isn't interested in individual freedoms or the separation of powers, it wants the state and the party to wield full control.

That's the political lesson that China's leadership is teaching Hong Kong.

At the same time, though, the city represents a dilemma, one which others will find themselves facing sooner or later.

For decades, Hong Kong was a model of efficiency and productivity, and the city was seen as one of the most business-friendly metropolises in the world.

China wanted to learn from Hong Kong.

But this relationship has now reversed. Today, China dominates the economy of Hong Kong; the momentum is now coming from the other side of the Sham Chun.

The city has become part of China, a reality that no government in the world calls into question.

But the risks that come with dependency on China, the second-largest economy in the world, can already be clearly seen in Hong Kong.

The former British colony, today a special administrative region of China, is located at the fault line of some of today's most pressing societal, political and economic questions. Like Berlin during the Cold War, it is a city on the front lines.

Kowloon: Right and Wrong

The district of Kowloon lies on the north side of Victoria Harbor and is among the most densely populated areas in the world, with 10 times more people per square kilometer than in Berlin.

West Kowloon is dominated by office towers, hotels and shopping malls. The city's largest and most modern courthouse is also to be found here.

East Kowloon is a district of the working and middle classes. Here, on one Sunday in late February, Leung Kwok-hung heads out, perhaps for his final day of freedom.

A slender 64-year-old, Leung is dressed in all black, his T-shirt bearing an image of Che Guevara.

The only splash of color is his yellow facemask.

Black and yellow are the colors of the democracy movement in Hong Kong.

Leung's ringtone is the Internationale.

But he will be forced to turn in his mobile phone on this day.

Because of his unusual hairstyle, Leung is known in Hong Kong as "Long Hair," and he has a reputation for being one of the city's most radical politicians.

The son of a single mother who earned her money as an amah for a British family, he grew up in poverty and became a construction worker.

He began his political career as a Maoist, though he turned his back on the ideology during the Chinese Cultural Revolution.

Later, he founded a leftist party, which he represented in Hong Kong's Legislative Council, where he pushed for democratic reform.

Since 1989, he has participated in a vigil every year on June 4 in commemoration of the Tiananmen Square massacre, while on every Oct. 1, China's national holiday, he would carry freedom's symbolic coffin to the grave.

He has been to prison several times, usually just for a few weeks at a time.

In the early morning hours of Jan. 6, police dragged him out of bed and arrested him, along with 52 other politicians and activists. They had all taken part in an internal, opposition primary election in preparation for parliamentary elections, which were ultimately postponed.

Hong Kong authorities consider the vote to have been a "subversive conspiracy," and according to the National Security Law passed in 2020, this vaguely defined transgression is punishable with a sentence of up to life in prison.

Leung was initially released on bail, but was called back in on this Sunday. He has climbed police barricades and held passionate speeches in his protesting days.

But he is quiet on this morning, as he makes his way from his apartment to the police station. "I have no idea how long they will lock me away for this time," he says. "But it could be a very long time."

Halfway there, he suddenly stops and begins rummaging through the small bag containing his underwear for prison. He is looking for a court ticket for his wife, who is waiting for him in front of the police station.

They only got married a few weeks ago, knowing full well what was coming. A group of party allies is there as well.

Leung excuses himself and goes to smoke another cigarette. When he comes back, he hugs a friend's young daughter before disappearing inside the police station.

The next day, Leung and 46 others are led into the West Kowloon courtroom. He can't be seen because the room is overflowing with defendants, leaving no capacity for spectators, who can only watch via video. And the cameras only show the judge, the prosecutors and the defense attorneys.

The hundreds of supporters gathered in front of the courthouse aren't even allowed into the building. They start chanting protest slogans: "Fight for freedom! Stand with Hong Kong!"

It is the first larger demonstration in the city for months, but it doesn't last long. A group of police surround the courthouse and the demonstrators back off.

The reading of the indictment is scheduled for just a day, but the motions for bail and the countermotions from the public prosecutors last deep into the night. Shortly before 2 a.m., one of the younger defendants faints and the judge calls a recess.

The defendants are returned to prison in the early morning hours, only to be brought back to the courthouse just hours later.

It would be the same story for four straight days, with six defendants having to be sent to the hospital, including Leung. His application for bail is rejected.

Along with Leung, the core of Hong Kong's democracy movement is in pre-trial detention: The law professor Benny Tai, who helped initiate the Umbrella Protests of 2014; the student leader Joshua Wong; and a number of former lawmakers.

The trial against the group of 47 is a massive blow to the opposition, and it will continue for months, if not years. The resulting sentences will also likely be for several years in some cases.

Western countries will likely register their objections, and may even impose sanctions. But the governments of Hong Kong and Beijing will reject all such criticism.

In the Hong Kong of the future, there is no longer any room for political opposition, not even for a former Maoist like Long Hair.

Hong Kong: A Tiger in Bed

Politician Lau Foto: Anthony Kwan / DER SPIEGEL

The name Hong Kong originally referred to an inlet on the island that protects Victoria Harbor from the open sea.

Today, this island's narrow coastline is covered with skyscrapers housing banks and insurance companies, which dominate the city's skyline.

It is here where the city's chief executive, its parliament and most foreign representations are to be found.

Victoria Peak rises in the background, where the wealthy live among the plane trees. In February, a 300 square-meter apartment (3,230 square feet) here was sold for $59 million.

At the foot of the hill are the headquarters of the New People's Party, founded by Regina Ip, a 70-year-old, pro-China politician whose severity is reminiscent of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

Like Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam, Ip is part of the "handbag party," a group of able women officials who started their careers under the British and have risen further under the Chinese.

As secretary for security, Ip made the first attempt to introduce a national security law in 2003, something that Hong Kong was required to do under its 1997 Basic Law. But she failed badly.

Half a million people took to the streets in opposition to the law, representing the first mass protests since Hong Kong was returned to Chinese control. Beijing elected to refrain from pushing the law through anyway and Ip resigned.

The defeat still bothers the pugnacious politician. Of course she supports the draconian security law that has now been put in place, she says. Had her plan been accepted back in 2003, she adds, it would have been far less severe.

"It is better to pass such laws when you're not in a crisis," she says. But following the at-times violent protests triggered by a controversial extradition law, she says, Beijing had little choice.

Ip is also supportive of the electoral reform that China's National People's Congress passed for Hong Kong in early March. "Half-baked," is how she describes the rudimentary democratic system that has for years essentially excluded the possibility of an anti-Beijing majority.

To eliminate even the theoretical possibility of such an outcome, the system is now being changed even more to China's advantage. "Beijing cannot afford the office of chief executive falling into the hands of foreign powers," says Ip.

From now on, only "patriots" are allowed to govern in Hong Kong, and the government has reserved for itself the right of determining who a patriot is.

Patriotism is "holistic love" of the fatherland, according to the formulation of one Hong Kong minister, which includes love of the Communist Party.

But even Regina Ip seems a bit uneasy with the aggression displayed by politicians who are even more pro-Chinese than her when it comes to denouncing anyone suspected of not being sufficiently patriotic.

It feels "as if a cultural revolution storm is going to sweep across Hong Kong," she said in defense of an official who allegedly did not move fast enough to remove all traces of the protest movement from the city.

A few streets away from Ip's office sits a woman who saw all of this coming: the human rights activist Emily Lau, 69, who started her career as a journalist for the BBC and other outlets.

We meet for breakfast at the Foreign Correspondents' Club, a city institution and the setting for a John le Carré novel – and a place where the Hong Kong elite rub elbows.

A lot of people stop to greet Emily Lau – there aren't many here who don't know who she is.

In December 1984, she asked Margaret Thatcher a question that would turn out to be prophetic and which made Lau famous: "Prime Minister, two days ago you signed an agreement with China promising to deliver over 5 million people into the hands of a communist dictatorship. Is that morally defensible?"

Cinema-goers watch a film at the harbor in Hong Kong's Central district. Foto: JEROME FAVRE / EPA-EFE

Cinema-goers watch a film at the harbor in Hong Kong's Central district. Foto: JEROME FAVRE / EPA-EFEThatcher had just returned from Beijing, where she had sealed the return of Hong Kong with a declaration, which came to be known as "one country, two systems."

Thatcher's response is just as famous as Lau's question: Everybody in Hong Kong was hailing the joint declaration, she said, suggesting that Lau was "the solitary exception."

Lau was unimpressed and decided to go into politics. She was elected seven times to one of the few directly elected parliamentary seats and was head of the Democratic Party for four years.

And she became a target for Chinese propagandists. In the 1990s, the Chinese leadership declined to allow her to travel to mainland China.

When China offered to lift the ban several years later, she declined, saying: "I'm not a dog that jumps on command."

Today, Lau is one of the last prominent politicians who dares to openly criticize China.

At the same time, she knows that the China of today is not the same as it was in 1984 or 1997 – which is something, she believes, that many people ignore.

A few years ago, she was with a group of university students, some of whom were speaking out for Hong Kong's independence.

"I said: No, I support 'one country, two systems.'

And you know what that means?

That we are lying in bed with a tiger.

But you are poking the tiger in the eye.

When the tiger wakes up, you will be killed – and a lot of people will be injured."

Central: Crazy Rich Asians

Tycoon Zeman Foto: Anthony Kwan / DER SPIEGEL

The Foreign Correspondents' Club is housed in one of the last remaining colonial buildings in Central, the city's financial district and a nightlife hub. Almost all the others ultimately had to make way for modern skyscrapers.

The vibrant streets of the district – shaded during the day and lit up by neon signs at night – are straight out of "Chungking Express," the famous Hong Kong film by Wong Kar-wai.

Even today, despite the National Security Law and the pandemic, masses of people stream through the streets, on their way to the office in the mornings and headed for the restaurants in the evenings.

In the middle of Central is the bar and entertainment complex Lan Kwai Fong. It was developed by Allan Zeman, who was born to Jewish parents in Germany in 1949, before growing up in Canada and then becoming one of Hong Kong's real-estate tycoons.

A tall man with a shaved head, Zeman looks much younger than he is. In 2007, the South China Morning Post chose him as "Stylemaker of the Year."

He made his first million trading in textiles, with Hong Kong still home to factories at the time, before they moved to the mainland.

In 1975, Zeman himself moved to the city and quickly became part of the establishment.

In 1997, the British invited him to the handover ceremony, and he became a Chinese citizen in 2008.

Today, Zeman is a member of the Economic and Employment Council, which advises the chief executive.

"I'm just coming from lunch with a couple of bankers," he says. "The world is drowning in money. The stock markets are like casinos." That is particularly true of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, which is just a five-minute walk from Zeman's office.

The amounts of money currently flowing out of and into China are larger than ever before.

Fully 154 companies had their IPOs in Hong Kong last year.

And in January alone, half as much Chinese money crossed the border as in the entire previous year.

It was Hong Kong's best January on the stock market in 40 years.

It is impossible to know how long this explosive growth will last, but the long-term outlook is good.

Hong Kong's position as a financial hub in Asia is akin to London's stature in Europe, though Hong Kong's stock market is now even larger.

And China is just as hungry for foreign capital as the rest of the world is for Chinese money.

It isn't easy these days to set up appointments with brokers in the city. They simply have too much to do.

In February, the British bank HSBC even pivoted its focus toward Hong Kong, saying the future lies in Asia.

But for the last several weeks, in parallel with the mounting reports of arrests and trials, uneasiness has begun growing in the financial industry.

According to the Financial Times, international law firms have been fielding an increasing number of queries from their clients as to whether arbitration clauses are safe in Hong Kong.

The Heritage Foundation in the U.S. even took the step of dropping Hong Kong from its annual Index of Economic Freedom.

"Nonsense," says Allan Zeman, adding that such reactions are overwrought and politically motivated. Hong Kong's future as a financial center is secure, he says.

But can the free economy operate in places where political freedoms are restricted?

And how would that look?

Would the result be comparable to Singapore, the semi-authoritarian city-state that the people of Hong Kong used to poke fun at?

"Singapore has a kind of democracy, but no freedom," as the saying goes in Hong Kong. "Hong Kong has no democracy, but freedom."

But the way things are currently looking in Hong Kong, the city may soon enjoy neither of them.

Publisher Lai: Beijing has no interest in individual freedoms. The emphasis is on state control. Foto: Isaac Lawrence / AFP

Publisher Lai: Beijing has no interest in individual freedoms. The emphasis is on state control. Foto: Isaac Lawrence / AFPBehind Zeman's office door is a stand holding an umbrella bearing the name Giordano.

It is the name of the company founded by another prominent Hong Kong tycoon.

He, too, got his start in the textile business before shifting his attentions to another industry.

His name is Jimmy Lai, the 73-year-old publisher of Apple Daily, Hong Kong's most widely read opposition newspaper.

Zeman has known Lai for 48 years. "Jimmy used to produce sweaters for me," he says.

"We were kids, almost the same age."

Lai, who fled to Hong Kong from the mainland in 1959, started as a child laborer, but managed to work his way all the way to the top.

He became politicized by the Tiananmen Square uprising in spring 1989, whereupon he sold his company, founded a publishing house, and became one of China's sharpest critics.

Zeman and Lai found themselves on divergent paths.

At the height of the protest movement in 2019, Jimmy Lai met with high-level U.S. government officials and urged them to apply sanctions to China.

A year later, he was arrested and charged in December with "conspiring with foreign forces."

Like Long Hair, he is facing a potential sentence of life in prison.

What did Zeman think when he saw his former business partner before the court in handcuffs and chains?

"Jimmy crossed a red line," Zeman says tersely.

"Breaks my heart."

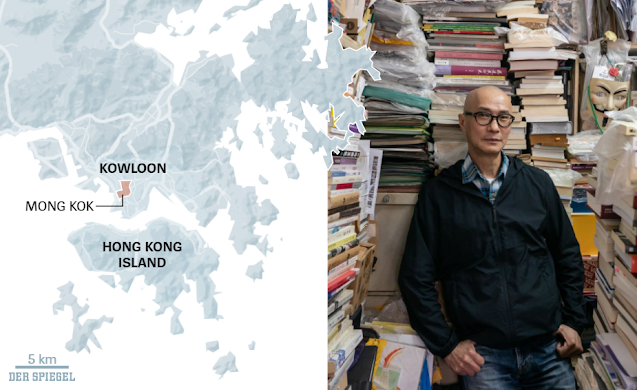

Mong Kok: A Culture of Goodness

Publisher Pang Foto: Anthony Kwan / DER SPIEGEL

The buildings of Mong Kok are even more closely packed together than in Central, and many apartments in the district only have one or two rooms.

In older films from Hong Kong, the district was frequently used as the setting for social dramas and gang warfare.

More recently, though, it has been police and demonstrators facing off in the quarter rather than the notorious organized crime syndicates.

The district is considered to be particularly rebellious and opposition graffiti can still sometimes be seen on the walls.

The 10th floor of a rundown warehouse building provides the headquarters of Sub-Culture, the publishing house run by Jimmy Pang – two rooms with books piled up to the ceiling.

A slender and athletic 65-year-old, Pang isn't just a publisher, he is also a kung-fu master.

In the 1970s, he worked on a film together with Bruce Lee, the icon of his generation. Pang is a devout Buddhist – "which is why I shave my head."

His bestselling titles hang on the wall: a dictionary for the Cantonese spoken in southern China and Hong Kong; a biography of the widely hated predecessor to the current chief executive; a collection of quotes from Chris Patten, the last British governor of Hong Kong.

For Jimmy Pang, Hong Kong's decline began with the 1997 handover and was capped off by the National Security Law.

"It's not just that we can no longer produce critical books about Tibet, Taiwan or Hong Kong," he says.

"Many authors no longer dare to write, we publishers no longer dare to publish, the printers are wary of printing and the bookstores shy away from selling."

Only two types of books are safe: "cookbooks and books about astrology."

In late 2015, Beijing arrested several publishers and had them brought to the mainland. One of them, who was also the author of a juicy send-up of Communist Party elites, is serving a long prison sentence, though the Chinese insist it was actually for a hit-and-run.

Another, Lam Wing-kee, was allowed to return to Hong Kong after several months, but has since fled to Taiwan and founded a new bookshop there.

Jimmy Pang isn't thinking of leaving, saying he has a mission of "maintaining the spirit of Hong Kong," a spirit that is greater than the sum of its Cantonese, Chinese and British parts.

"It is a culture of goodness," he says, "of justice and freedom."

Dover and Zelda Chung, 54 and 53 years old respectively, live five residential buildings away from Jimmy Pang's publishing house.

The married couple works in the financial division of an insurance company, while their daughter Margaret has just completed her university studies in England.

Her parents now want to join her there.

Their apartment is 60 square meters, which is large for Mong Kok. A map of Greater Manchester hangs in the kitchen. Two pins mark their new home and the city's Chinatown.

Many children of middle-class couples in Hong Kong head abroad for their studies. But it is a rather new phenomenon for their parents to uproot and follow them – and has to do with a decision made by the British government.

London sees the passage of the National Security Law as a violation of the Sino-British Joint Declaration, which guarantees Hong Kong a "high degree of autonomy" until 2047.

As a consequence, Prime Minister Boris Johnson decided to grant holders of British overseas passports and their family members permission to live and work in the UK.

In theory, that applies to 5 million people, including the Chung family.

"The overseas passports are the prerequisite," says Dover Chung, "but that's not the reason" for leaving.

Those reasons have amassed over the last several months: the aggressive behavior of the police against the protest movement; the curtailing of freedoms; and the erosion of the rule of law.

The family made its decision once the National Security Law was passed: "Hong Kong isn't safe anymore," says Zelda Chung.

They carefully considered all the pros and the cons, looking at mundane concerns such as the weather and the food, and more serious aspects such as their families and job security.

But, says Dover Chung, he is prepared to look for a new job, even if it is as a parking attendant.

"Margaret has already found me a job. The hourly wage is 8.50 pounds."

They plan to move into their apartment in England, which they bought years ago hoping to boost their pensions with the rent revenues.

It is the same size as their current place in Hong Kong, but cost only a fifth of the amount: 200,000 pounds.

"It was a good investment," says Zelda Chung.

Kwai Chung: Generation 2019

The man who asked to be called Dan has proposed that we meet in a hotel.

A friend of his with connections has managed to get him the keycard for a room on the 35th floor.

There are a lot of empty hotel rooms in Hong Kong these days.

Dan was a "frontliner," part of a team of 12 young people who fought with the police during the protest movement in summer and fall 2019.

His story, he says, is typical of Generation 2019: the son of a "blue" family, meaning pro-Chinese, initially not particularly interested in politics, but so shocked by the brutality of the police during the first days of the movement that he joined and soon found himself standing on the frontlines being doused by a water cannon.

He took part in numerous street battles and was also on hand for the siege of the Polytechnic University, which proved to be one of the most violent clashes with the police. "I can't explain myself why I was never caught," he says. "I was probably just lucky."

He says he established friendships in 2019 that he still maintains today.

Dan is a tall, slightly chunky 31-year-old wearing a black baseball cap and a black mask.

He is laid back and works on the fringes of the erotic industry, which he jokes about.

But what he is now doing, a little over a year after the end of the protest movement, is rather serious: He looks after activists who have gone underground.

"The National Security Law," he says, "has changed everything."

A new wave of protests, he says, is unimaginable, and even private discussions have become risky.

The movement, he says, has essentially gone into hibernation.

"We are now focused on helping those who are wanted by the police."

Dan has taken responsibility for four friends, finding them ever new places to stay, doing their shopping and trying to keep their spirits up.

"I'm quite good at that," he says. There are rumors circulating about some of those he is helping that they have left the territory.

"But that's not true. They're still here."

One country has offered to take them in, he says, but getting them there would be tricky.

In August, a boat with 12 activists onboard – some of whom had already been charged but not yet taken into custody – set off from a bay in northeastern Hong Kong bound for Taiwan.

The vessel was intercepted by the Chinese coast guard and 10 of the 12 were taken to court on the mainland and handed prison sentences of between seven months and three years.

Helping friends flee the territory is also risky, Dan says, with chances for success "no more than 50 percent." And the penalty for helping people flee is much higher than for illegally crossing borders.

"From that perspective, we failed," Dan says, "just like protest movements that came before. But the fight goes on."

The movement did achieve one thing, after all, he says: It attracted the attention of the entire world and generated sympathy for Hong Kong's fate.

That alone was worth the risks he took, he insists, and continues to take.

Several days later, he agrees to a second meeting for photos. This time, he proposes Kwai Chung, a port district that used to be home to industrial buildings and factories. Traffic on a major arterial streams past warehouses and containers.

When Dan poses on a vacant pedestrian bridge for a portrait, a passerby appears and starts taking pictures as well.

Our casual chitchat immediately stops, and we exchange uneasy glances. The passerby disappears again a short time later, and it is unclear what had caught his interest. But it's hard to imagine he was there for the area's charms.

With Beijing's growing influence, mistrust has grown in the city.

For over 150 years, Hong Kong was the colony of a now-faded empire and for the last quarter of a century, it has been part of a powerful country that is developing into an empire of its own.

Perhaps it was an illusion from the very beginning that Hong Kong would be able to maintain a "high degree of autonomy" for 50 years.

As things currently look, the city has merely been passed from one master to another.

One that is much more repressive.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario