The US Rediscovers North Africa

Washington has new concerns that have reignited its interest in the region.

By: Hilal Khashan

Earlier this month, U.S. Secretary of Defense Mark Esper visited Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco on a diplomatic tour of North Africa. The trip, one month before the U.S. presidential elections, was significant because it came amid a recent escalation in terrorism that accompanied the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as increased Chinese and Russian naval exercises in the Mediterranean.

The United States has long considered North Africa a friendly region. But the perception of North Africa started to shift after the 9/11 terrorist attacks. In 2007, President George W. Bush announced the establishment of the United States Africa Command in response to the rise of al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb, a group that originated in Algeria, that same year.

In August 2014, President Barack Obama held in Washington the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit, where economic and security cooperation dominated the agenda. Notably, this was a time when competition between Africa’s fast-growing economies was rising and Islamic militancy in the Sahel region was surging.

The focus in these interactions was security and counterterrorism efforts. Following Esper’s visit, however, the U.S. appears to be shifting its attention in its relations with North Africa to other global challenges, namely China and Russia.

Keeping Others at Bay

While in North Africa, Esper signed separate 10-year military cooperation agreements with Tunisia and Morocco, and discussed cooperation on a number of defense matters with the Algerian president. The partnerships are ostensibly about fighting terrorism and finding areas for collaboration with countries that Washington sees as key to establishing security in Africa, but they’re also aimed at keeping China and Russia at bay.

Indeed, the U.S. is concerned about Russian, Chinese and, more recently, Turkish efforts to expand their naval presence in the Mediterranean and boost their economic and military influence in the region. Russia is already a major supplier of military hardware – including Su-35 fighter jets, S-400 surface-to-air missiles and Iskander-E ballistic missiles – to Algeria, and China is its top supplier of imports.

In 2015, Russia and China began organizing joint naval exercises in the Mediterranean, and in 2017, they held live-fire drills. The two countries are also trying to find a location to use as a port of call in the Mediterranean or the Atlantic off the coast of either Morocco or Mauritania.

Their involvement in North Africa is motivated by different objectives, however. Russian President Vladimir Putin wants to restore Russia’s past glory in which access to the Mediterranean was central to achieving great-power status. China, on the other hand, is far more ambitious: It’s trying to acquire blue-water capabilities to help protect its access to sea lanes, and North Africa’s Mediterranean waters and Atlantic coastline are part of this global strategy.

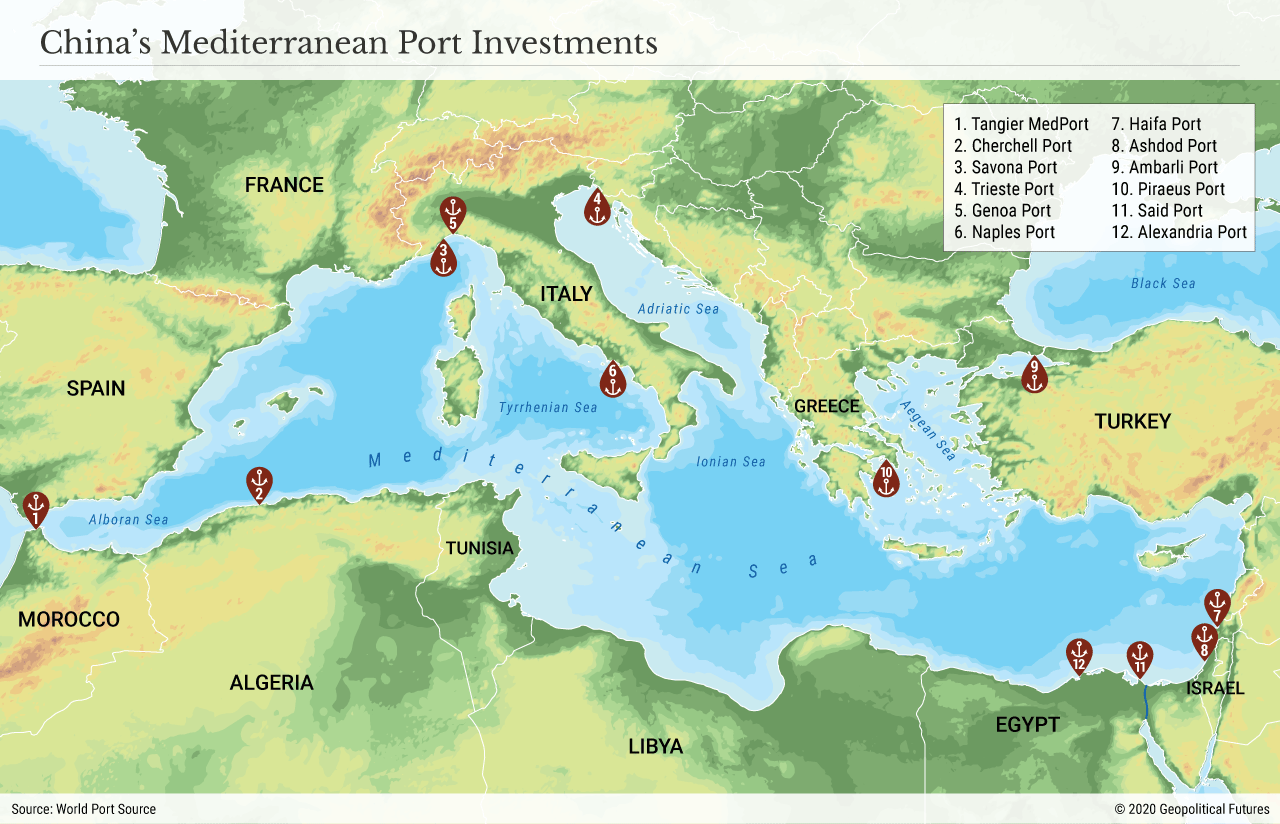

Its push into the Mediterranean is critical for the success of the Belt and Road Initiative. It has already invested in expanding Greece’s Piraeus Port, and its Cosco shipping company signed agreements to operate the Tangier Mediterranean Port Container Terminal and Algeria’s Cherchell Port.

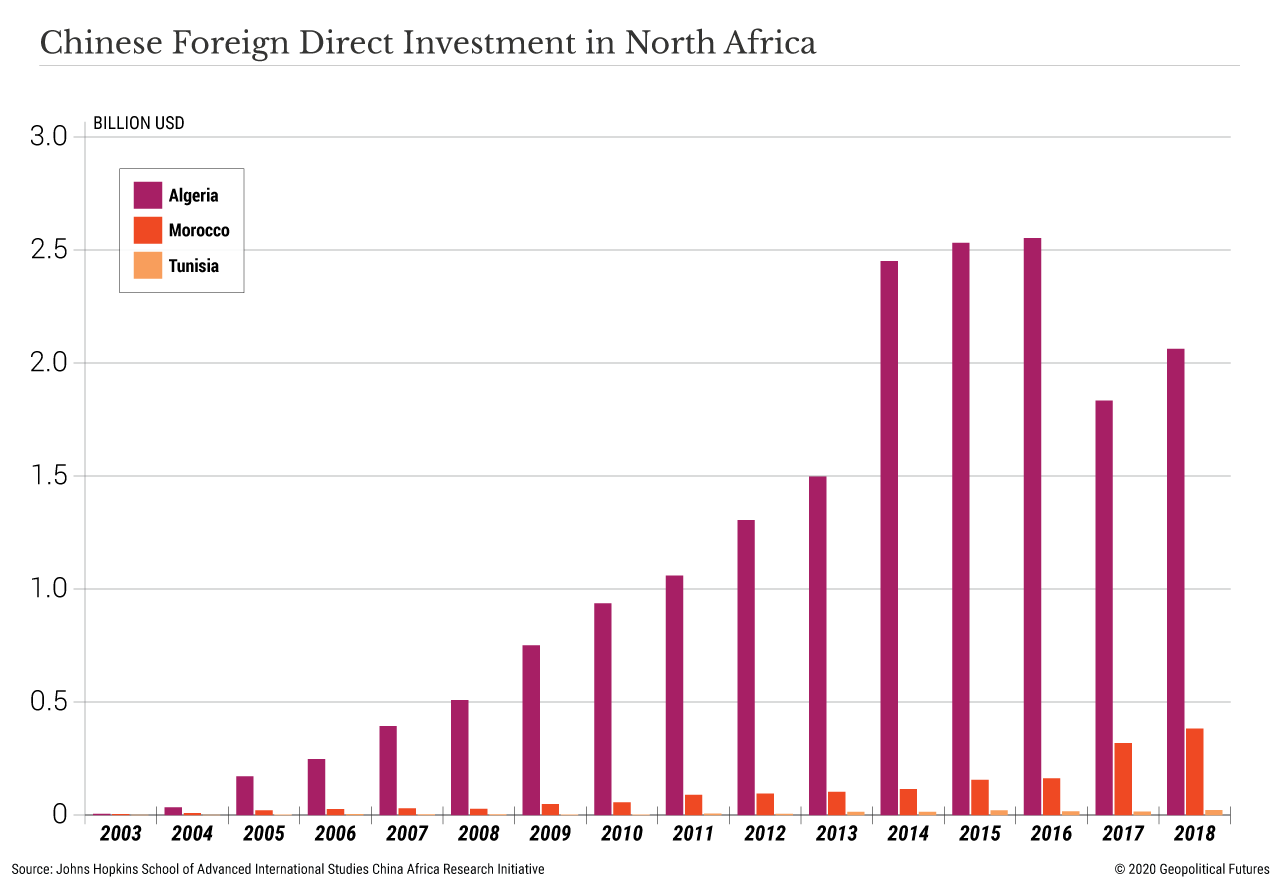

Washington’s top concern, therefore, is Beijing, whose growing influence in North Africa is a result of both the lack of Western backing for countries in the region, at least according to them, and Beijing’s desire to expand and promote its own industrial base.

In Morocco, King Mohammad VI has been exasperated with the lack of U.S. support for his country in the dispute over Western Sahara and Washington’s unwillingness to provide missile systems that would put Morocco’s defense capabilities on par with Algeria’s.

He has therefore looked elsewhere – namely, to Beijing – for assistance. Following the king’s visit to China in 2016, Morocco purchased the WS-2 400 mm multiple-launch rocket system and Sky Dragon 50 surface-to-air missile system from Beijing.

China is also competing with France, which has invested heavily in Morocco’s infrastructure since the country gained independence in 1956, for a contract to construct the Marrakech-Agadir high-speed rail line. China Communications Construction Co. has also expressed interest in investing $10 billion to build the Tangier Tech City project. But Morocco has yet to decide on the offer given the level of Western opposition to Chinese incursions into the West’s historical sphere of influence.

Attitudes Toward China

Many in North Africa, however, still prefer partnering with the West over China because of concerns over Beijing’s long-term objectives. Tunisia, for example, signed on to Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2018 but has yet to translate this into any actual partnership deals. Though China is now the third-largest supplier of imports after France and Italy, the political elite appear unwilling to open up to China beyond providing rhetorical support.

They, like others in North Africa, are skeptical of China’s charm offensive and question its goals in providing substantial sums of cash for development projects.

They’re also wary of the cultural differences between themselves and the Chinese that could make cooperation difficult. (One example of this culture gap comes from Algeria, where locals objected to the presence of Chinese construction workers in a suburb of Algiers and disapproved of their culinary habits that conflicted with Islamic norms.)

Still, Algerians and Moroccans find China’s pragmatic, business-oriented approach appealing. Both countries’ governments appreciate Beijing’s emphasis on economic development and willingness, unlike Western countries, to eschew political intervention and human rights issues. Indeed, China is now the top economic partner for both Algeria and Morocco.

What concerns them, however, is that accepting Chinese investment could backfire in the future. China has tried to allay these fears, arguing that as a victim of the Opium Wars, it cannot imagine becoming a colonial power itself. It has also reminded Algerians of the tremendous political support it gave to Algeria’s National Liberation Front during its independence war against France in 1954-62. (China’s treatment of Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang, however, casts doubt over Beijing’s claim to be an ally.)

It’s unlikely, however, that the U.S. will allow Morocco to become a Chinese satellite state and to participate in the Belt and Road Initiative. Washington trusts Algeria’s independent foreign policy and ability to keep its distance from Beijing. Esper’s recent visit to North Africa seems to have opened a new chapter in U.S. efforts to contain China’s global economic offensive.

There is no reason to assume that China’s economic activity in North Africa will achieve better results than it has had in any other region of the world. Moreover, China is likely incapable of using whatever inroads it makes in North Africa to increase its footprint in Africa’s heartland.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario