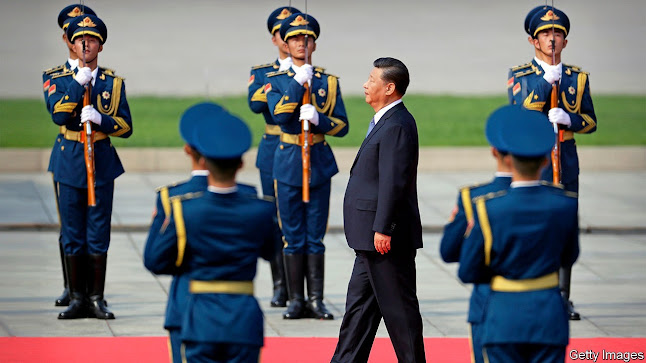

The missing successor

China’s most senior officials endorse economic plans for years ahead

But they left one little thing out

Almost exactly ten years ago, in a typically roundabout way, China made clear who its next leader would be. A man who, not long earlier, had been far less famous than his folk-singer wife was made vice-chairman of the Communist Party’s Central Military Commission. Sure enough, two years later, he took charge of the party and the armed forces and became China’s most powerful ruler since Mao Zedong.

Were precedent to be followed, a meeting of senior officials in Beijing this week would have provided just such a clue about who would succeed Xi Jinping. It provided nothing of the sort.

That is no surprise. When China’s constitution was revised in 2018 to scrap a limit of two five-year terms for the post of state president, which Mr Xi also holds, it was a clear signal that he did not wish to step down when his ten years were up. As head of the party, he was not bound by any term limit. But his predecessor, Hu Jintao, had given up both party and state roles in quick succession. Mr Xi had been expected to follow Mr Hu’s lead.

For anyone still in doubt about Mr Xi’s intentions, the party’s just-concluded meeting gave a hint as obvious as the one in 2010 that heralded his rise to power. A communiqué issued on October 29th, at the end of the four-day conclave of its roughly 370-strong Central Committee, said the gathering had endorsed “recommendations” for a five-year economic plan and a blueprint for China’s development until 2035 (full details of these had yet to be published when The Economist went to press). But it made no mention of any new civilian appointment to the military commission.

The post of vice-chairman is an important one for any future leader to hold before taking over. Mr Hu got the job three years before he became general secretary. Without experience of how military command works, a party chief may find it hard to assert control over the army.

There are still two uniformed vice-chairmen. But the continuing absence of a civilian at that level means China has no leader-in-waiting when time has all but run out to start learning the ropes before the party’s 20th congress in 2022. A civilian vice-chairman would also be a member of the Politburo’s Standing Committee.

But a reshuffle of that seven-member body in 2017 did not include anyone of the usual sort of age of someone being groomed for succession.

There are occasional complaints in China about Mr Xi’s seeming determination to hold power indefinitely. In August Cai Xia, a public intellectual, was expelled from the party and stripped of her pension by its most prestigious academy for training leaders, the Central Party School, where she had studied and taught for 20 years before retiring.

Among comments that apparently resulted in her punishment was her description of Mr Xi’s scrapping of the two-term limit as something the Central Committee had been forced to swallow “like dog shit”. Ms Cai is now abroad.

But in so far as can be guessed from China’s opaque political workings, Mr Xi remains as powerful as ever and seemingly fit enough to keep going well beyond 2022. He will turn 69 that year—by convention too old to remain in office, but that is not a hard-and-fast rule. While liberals like Ms Cai grumble—as, no doubt, do those who have suffered as a result of his ruthless campaign against corruption and his political purges—there is little sign of strong anti-Xi sentiment among the public.

In some ways this has been a good year for Mr Xi, with many Chinese proud of their country’s success in crushing covid-19 and getting the economy back on track. Party propagandists have been working hard to boost such sentiment. The term “people’s leader”, rarely applied to his post-Mao predecessors, is sometimes used in state media when referring to Mr Xi (the Politburo used it for the first time last December).

It may also, however, be an anxious time behind closed doors. Party congresses rubber-stamp decisions that have been made in secret beforehand. Even though the next one is still two years away, the build-up is a tense time in Chinese politics as leaders bargain over policy and appointments.

The party’s 18th congress, at which Mr Xi came to power, followed a protracted political struggle highlighted by the dramatic downfall of Bo Xilai, a contender for highest office. There is no sign that Mr Xi faces another such challenge. But in July the party launched a pilot scheme in a handful of places for a new purge, this time aimed at the judiciary, police and secret police.

One stated aim is to root out “two-faced people” who are disloyal to the party. It will be rolled out nationwide next year and wrap up early in 2022, a few months before the 20th congress.

It is not yet clear how Mr Xi intends to exercise his power beyond the congress. He could simply keep his current positions. Another rumoured option is that he might prefer an even grander title than that of general secretary, which has not always indicated that the holder wields supreme power.

In the 1980s Deng Xiaoping, whose authority stemmed from his position as chairman of the military commission, sacked two general secretaries; Mr Hu became general secretary in 2002 but remained overshadowed by his predecessor, Jiang Zemin, who held on to the crucial military position until 2004. Mr Xi could revive the title of party chairman (abolished in 1982) and raise himself to the great helmsman’s hallowed level.

He will certainly use the congress to install more of his protégés. By that time the prime minister, Li Keqiang, will have served his constitutionally mandated maximum of two terms. Mr Li was not installed by Mr Xi, who may look forward to appointing someone closer to him. Unusually, there is no obvious person who has the experience (serving as deputy prime minister is usually a prerequisite), is the right kind of age (67 or younger is the norm) and crucially, who is close to Mr Xi.

Leaving this choice until closer to the time may not bother him, however. Since Mr Xi became leader, the prime ministership has become less important. He has taken over its core responsibility: directing the economy.

The biggest unknown is who would emerge as China’s paramount leader if Mr Xi suddenly becomes unable to rule, as a result of death or illness. There is no clear line of succession within the party—without Mr Xi, no one in the currently 25-member Politburo would stand head and shoulders above the rest.

Younger leaders, such as the party chief of the south-western region of Chongqing, Chen Min’er, who has long been tipped as a forerunner for post-Xi leadership, may lack sufficient seniority to take over in an emergency. Mr Xi’s sudden departure could plunge China into political turmoil.

The Central Committee’s just-concluded meeting may have made Mr Xi’s plan to retain power in 2022 even more certain. It has done nothing to instil confidence in China’s political future.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario