The American Dream: Bringing Factories Back to the U.S.

By Matthew C. Klein

For years, investors cheered as U.S. companies shifted manufacturing overseas to reduce costs and boost profit margins. That could soon start to change, with decades of offshoring replaced by reshoring.

The shortages of personal protective equipment and other essential items during the early stages of the pandemic were a powerful reminder that corporate managers’ obsession with efficiency and cost-cutting at the expense of diversification and resiliency had made the American economy vulnerable.

A report from the McKinsey Global Institute found “180 products across value chains for which one country accounts for 70% or more of exports, creating the potential for bottlenecks.”

Worse, many of those products come from an increasingly hostile China, a circumstance with profound national-security implications for the U.S. and other democracies. That’s why Democrats and Republicans alike are looking for ways to revive U.S. manufacturing.

They’ll have to work hard. Despite the trade conflict, the coronavirus, and fear of a new cold war, a recent survey by the American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai found that 71% of U.S. manufacturers had no plans to move production out of China, while only 4% said they would transfer some to the U.S.

Moreover, even those that expected to move some production from China planned only small changes, not wholesale shifts in supplier relationships.

U.S. companies have directly invested about $260 billion in Chinese operations since the early 1990s, according to an analysis from the Rhodium Group. Replacing those assets elsewhere would be expensive—especially if the new property, plants, and equipment were in America—and the running costs would be far higher, as well.

The worst-case scenario for investors is that they will have to bear trillions of dollars of losses as companies write down stranded assets, are forced to hold more inventories, and shift operations in ways that lower margins.

The good news is that reshoring doesn’t have to hurt. The past few decades of globalization drove business cycles closer together and made companies increasingly dependent on global sales.

Researchers at the Boston Consulting Group’s think tank note that this came at the cost of tighter correlations of financial assets across countries, which means that reshoring could help diversify international stock portfolios and improve the risk/return trade-off for investors.

What’s more, investors stand to benefit if reshoring means a longer-term revival in innovation and flexibility in production. And higher operating costs could be offset by higher revenues, whether that’s through higher wages leading to greater consumer demand, government support, or some combination.

But reshoring won’t succeed without long-term commitments of money, attention, and expertise from the federal government. Companies have spent decades developing supply chains and procurement practices to cut costs to maximize returns for their shareholders and to cut prices for consumers, so the only way to alter their behavior is to offer new, radically different incentives.

“Made in America” won’t happen at scale unless Washington makes it significantly more profitable than the alternatives.

Some politicians seem to appreciate this, which explains why the latest batch of ideas from Democrats and Republicans—who are sometimes working together on these issues—are about structural changes to the U.S. economy. In 2019, Sens. Tammy Baldwin (D., Wis.) and Josh Hawley (R., Mo.) co-wrote legislation to make American manufacturing more competitive by lowering the value of the dollar, while Sen. Marco Rubio (R., Fla.) called for a new “industrial policy” to encourage business investment in the U.S. to counter Chinese protectionism. Since the pandemic began, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D., Mass.) and Rubio have cooperated on bills to reduce America’s “overreliance” on Chinese pharma products.

Both presidential candidates want to bring manufacturing back, but their strategies differ. Democrat Joe Biden has unveiled a plan to boost federal spending on U.S.-made goods, support research and development, change the tax code to discourage offshoring, and close loopholes in rules that already require Uncle Sam to “Buy American.”

“The U.S. economy is far less resilient to shocks than it needs to be,” Jared Bernstein, one of Biden’s top economic advisers, tells Barron’s. “Serial abuse from dumb industrial policy” inflicted by Washington hollowed out the U.S. manufacturing sector, he says, and America needs to “onshore certain supply chains, both medical and defense.” One area of particular concern is the “increasing share of defense procurement that comes from foreign production.”

That last concern is shared by the Trump administration, which has defended the legality of its tariffs, on the grounds that they are necessary to protect the “defense industrial base.”

But where Biden seeks to boost the nation’s manufacturers through additional procurement and R&D subsidies, Trump’s preferred approach has been corporate tax cuts and deregulation to encourage domestic investment, with levies on imports to discourage purchases of foreign-made goods.

The Pentagon has also recommended “direct investment in the lower tier of the industrial base…to address critical bottlenecks, support fragile suppliers, and mitigate single points-of-failure.”

At the same time, Robert Lighthizer, the administration’s chief trade negotiator, is encouraging other countries to buy more U.S. products. The most substantial deal has been with Canada and Mexico, and is notable for its emphasis on labor standards, local content requirements, and environmental regulations.

It also contained an unusual provision that any signatory that agrees to “a free trade agreement with a non-market country”—such as China—can get kicked out of the North American pact. George Magnus, the former chief economist of UBS and a China expert, told Barron’sthis could become a template for future deals that promote trade while excluding China. (Lighthizer didn’t respond to requests for comment.)

One thing that’s often lost in the debate on reshoring is that the U.S. is still a manufacturing superpower, producing more than $6 trillion of goods in 2019.

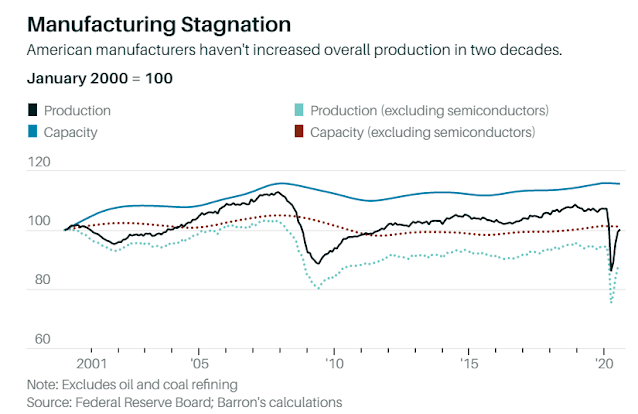

The problem is that, while the U.S. and global economies are far bigger than they were in 2000, America’s manufacturing sector hasn’t grown at all. Real output and productive capacity have been stagnant for two decades.

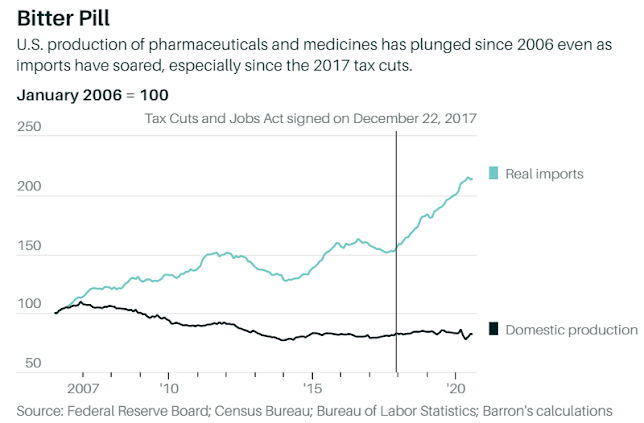

While it’s not surprising that labor-intensive textile and apparel manufacturing have almost completely relocated to places with low wages such as Bangladesh, many technologically advanced industries, including metals, machinery, and electronics have also shrunk significantly. The most extreme change has been in pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing, where production has dropped more than 20% since the peak in 2006.

The upshot is that the growth in both U.S. and global demand for manufactured goods since 2000 was satisfied entirely by foreign producers.

Imports displaced American production while American exports lost market share in foreign markets—even in high-tech sectors that Americans had pioneered, such as semiconductors and aerospace.

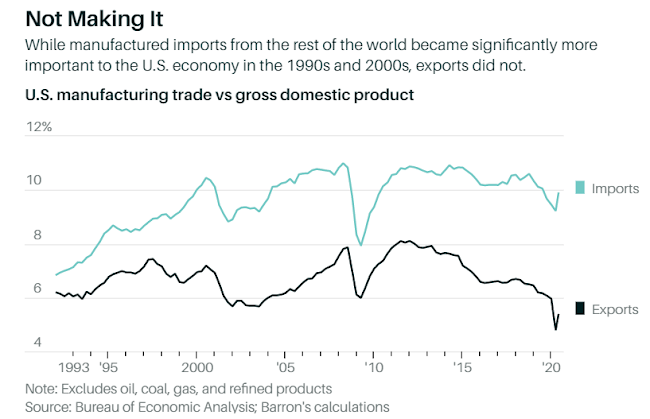

According to an analysis from the Coalition for a Prosperous America—a nonpartisan group backed by labor unions, ranchers, and manufacturers—imports from the rest of the world went from satisfying 23% of America’s domestic manufacturing needs in 2002 to 31% by 2019, with substantially larger increases in high-value sectors such as computers, electronics, appliances, machinery, and pharmaceuticals.

As a result, the U.S. now imports about $1 trillion more in manufactured goods than it exports each year, a deficit equal to roughly 4.5% of gross domestic product.

Imports ballooned at the expense of American workers because companies outsourced production—and the associated capital expenditures, which would otherwise have depressed profit margins—to countries with lower labor and environmental standards, bigger subsidies for businesses, and cheaper currencies than the overvalued U.S. dollar.

While American companies sometimes opened their own factories in China and other low-cost countries, they often preferred to contract the work out to third parties. (Think of Apple and Foxconn, the electronics manufacturer that makes the bulk of the iPhones, in addition to videogame consoles, laptops, and televisions for other multinationals.)

Foreign profits of U.S. multinationals boomed—to shareholders’ delight—but the strategy came with significant costs. The offshoring fad hollowed out America’s ecosystem of suppliers, researchers, and skilled workers. The factories that remain are highly specialized and reliant on outside suppliers and capital equipment. That has had consequences for jobs, economic dynamism, and national security.

“What’s missing is the capability to pivot” to respond to sudden changes in demand, Erica Fuchs, a professor of engineering and public policy at Carnegie Mellon, said in recent testimony to Congress. Americans faced shortages of masks and ventilators in the first months of the pandemic, in part because medical-supply companies lacked U.S. “technicians and operators with the know-how” to adjust to changing circumstances.

In contrast, Chinese factories accustomed to making a wide range of goods for multinational customers could quickly adapt to redirect production, she tells Barron’s.

Technological progress often comes from tinkering and experimentation, which is harder to do if research, production, and design aren’t all in the same place. Fuchs, along with colleagues Chia-Hsuan Yang and Rebecca Nugent, found that companies that can cut costs by offshoring to lower-wage countries face fewer incentives to innovate.

That might have contributed to the sharp slowdown in U.S. productivity since the mid-2000s. Similarly, economists David Autor, David Dorn, Gordon H. Hanson, Gary Pisano, and Pian Shu found that American manufacturers that didn’t offshore production responded to competition from cheap Chinese imports by slashing their research and development spending.

This is a problem even in the heart of America’s high-tech economy—and it’s a long-term threat for investors. While Silicon Valley is now known for software, it originally prospered as a manufacturing center that supported fundamental scientific research in physics, electronics, and materials science.

Many of the world’s leading electronics hardware companies are still headquartered in Silicon Valley, but most don’t manufacture anything there.

Consider what this has meant for Intel (ticker: INTC). While Intel still makes the chips it designs, it has fallen behind rivals such as Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (TSM) and Samsung Electronics (05930.Korea) in manufacturing. Since the beginning of 2004, TSMC shares have returned almost 1,000%; Samsung’s have gained more than 400%; and Intel’s are up less than 100%.

Hassan Khan, who focused on the semiconductor and advanced-electronics industry when he was a consultant at McKinsey, says that TSMC and Samsung have an advantage, in part because they have practice making chips for a wide variety of custo

mers with different designs and preferences.

In contrast, Intel is vertically integrated and makes chips only for itself. That makes the two big foreign firms more flexible and innovative when it comes to production techniques than Intel, which recently raised the possibility of shifting at least some output to contract manufacturers.

There is historical precedent for vertically integrated manufacturers being left behind by the market: A similar fate befell IBM, once the world’s leader in silicon processing, Khan notes. One solution is to focus on design at the expense of production. Advanced Micro Devices (AMD) spun off its manufacturing arm into GlobalFoundries in 2009. That has been great for AMD’s stock, but less so for Americans’ ability to make the most sophisticated chips.

Rebuilding America’s high-tech ecosystem is doable, but it could take decades. Brookings Institution economist Geoffrey Gertz notes that China’s rise as a manufacturing power was a result of “a decadeslong intentional push by the Chinese government,” and that a comparable commitment would be necessary to restore what has been lost in the U.S.

China’s production ecosystem developed with the help of targeted infrastructure investment, generous subsidies for businesses, procurement rules that favored “indigenous” companies, and managed competition.

All of that could be part of a long-term American strategy, should voters decide it’s worthwhile. (State-sponsored technology theft, the suppression of workers’ rights, and lax environmental regulations probably wouldn’t be.)

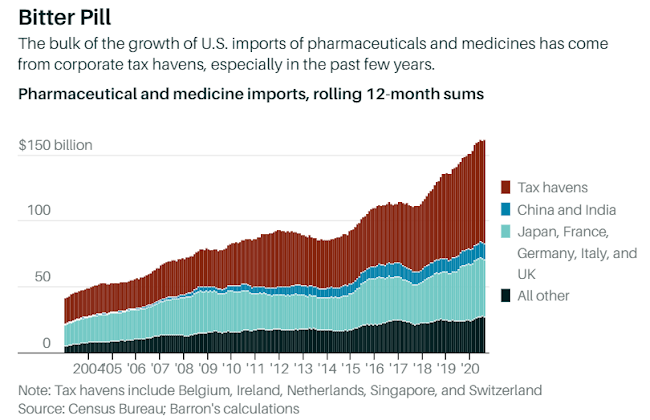

In the crucial pharmaceutical industry, offshoring was driven less by sustained government intervention than by glitches in the U.S. tax code. The U.S. headline corporate tax rate effectively stopped applying to the profits earned by foreign subsidiaries of American companies in the late 1990s.

That led to increasingly aggressive efforts to shift profits to tax havens, especially after the corporate tax holiday of 2005. The good news is that fixing those glitches could quickly lead to a resurgence in U.S. pharmaceutical production, although investors would have to accept higher effective corporate tax rates for pharma companies.

Inventing new drugs and figuring out how to produce them is expensive, but once that’s done it isn’t that hard to manufacture them at scale. That makes it relatively easy for pharma companies to shift their profits to low-tax jurisdictions.

“Many pharmaceutical companies conduct the bulk of their research and development in the United States, but then seek to minimize their tax burden by transferring their intellectual property to places like Bermuda and producing their drugs in yet another low tax jurisdiction like Ireland,” Brad Setser of the Council on Foreign Relations recently testified.

“The resulting products are then imported back to the United States, where typically they are often sold at a higher price than in the rest of the world.”

This behavior was turbocharged by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, which penalized U.S. companies for putting intangible assets offshore unless they also increased their physical assets.

The perverse result, Setser explains, was that a company “would automatically lower its calculated U.S. tax if it built a factory in Ireland” while “a firm that reduces its tangible U.S. assets by licensing its intellectual property to an offshore subsidiary that supplies global markets from a factory abroad would have a lower tax rate than a firm that keeps its factory in the United States.”

The results can be seen in the data. After steadily rising for decades, American production of pharmaceuticals and medicines peaked at the end of 2006 and has since declined more than 20%.

Over that same period, real imports have more than doubled. Much of the growth in imports of pharmaceuticals and medicines since then can be attributed to corporate tax havens such as Belgium, Ireland, the Netherlands, Singapore, and Switzerland. Since the end of 2016, 70% of the growth in U.S. imports of pharmaceuticals and medicines by dollar value has come from these tax havens.

Bringing manufacturing back to America isn’t impossible by any means—especially in capital-intensive sectors such as electronics and pharmaceuticals. It may even benefit investors, at least in certain industries.

Success will depend on Americans’ willingness to commit to a long-term strategy and investors’ willingness to pay the costs.

The experience of the past few years suggests that rhetoric without major policy changes won’t do much, one way or the other.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario