|

Morocco is a unique country in the

Middle East and North Africa region. Having been conquered by the Umayyad

Caliphate in the early eighth century, it is the oldest and most

established Arab country. It is also the only Arabic-speaking territory

that the Ottomans failed to conquer. In 1558, the Saadi Arab dynasty, which

ruled Morocco for roughly 100 years, stopped the Ottomans in the Battle of

Wadi al-Laban and forced them to retreat to Algiers. Hailing from Hejaz in

Arabia and claiming to be a descendent of the Prophet Muhammad, Mulay

al-Rashid founded in 1666 the Alaouite dynasty, which continues to rule

Morocco today. Though it became a French protectorate in 1912, Morocco

gained independence in 1956, giving its people hope that it would adopt a

democratic system and begin on a path toward economic development that

would benefit all Moroccans. However, the country failed to make the

necessary changes, and its prospects for growth now look bleak.

Turbulent Start

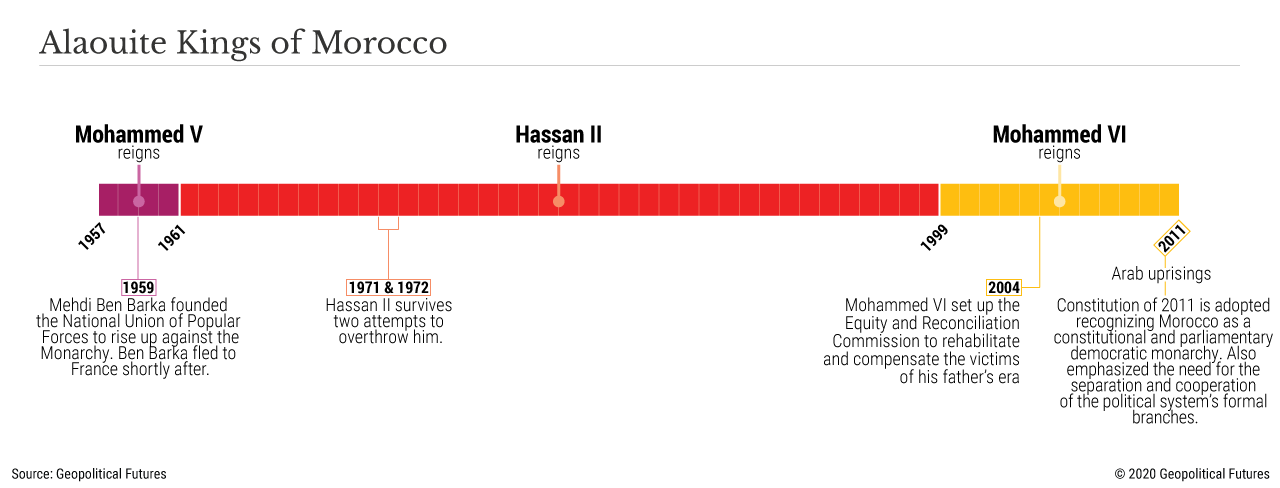

In 1957, Sultan Mohammed V declared

himself king of Morocco. He died in 1961 and was succeeded by his son,

Crown Prince Hassan II, whose turbulent reign lasted 38 years Two years

after he took over the throne, Morocco claimed sovereignty over Tindouf and

Bechar provinces, which instigated the Sands War with recently independent

Algeria. Hassan also faced a serious challenge at home with the rise of

Mehdi Ben Barka, who in 1959 founded the National Union of Popular Forces

and won international recognition. Hassan accused Ben Barka of scheming to

assassinate him, and strong indicators suggest that he ordered Ben Barka’s

abduction. Disillusioned with Morocco’s democratic transformation and

fearing for his life, Ben Barka sought refuge in France, where he mysteriously

disappeared in 1965.

(click to enlarge)

In the early 1970s, Hassan survived two

attempts to overthrow him. Citing the king’s failure to adopt necessary

reforms, two senior and trusted army officers staged a coup attempt in

1971. A year later, Hassan’s confidant and minister of interior, Mohammed

Oufkir, conspired with the Moroccan air force to shoot down his plane as it

arrived from Paris. These two incidents hardened Hassan, who unleashed an

unprecedented wave of terror against his opponents, including secret

trials, wholesale liquidation of dissidents and widespread arrests of

defectors. Hundreds of extrajudicial executions were carried out and many

more peaceful activists disappeared. The notorious Tazmamart prison, where

dozens of inmates died after being tortured and living in appalling

conditions, became a symbol of the country’s downward spiral. In 1999,

Hassan’s son, Mohammed VI, took over as king and, in 2004, set up the

Equity and Reconciliation Commission to compensate the victims of his

father’s era.

Mohammed VI was well aware of the

difficulties his father encountered while trying to stabilize his regime.

In January 2011, amid the Arab Spring uprisings, he established the Royal

Moroccan Youth Movement to try to preempt protests similar to those that

took place in Tunisia and Egypt. Its members were dubbed el-Ayasha, or

those who say long live the king. It was conceived as a paramilitary

organization and comprised delinquent and uneducated young men whose

primary function was to prevent the emergence of opposition groups. The

movement believed the king was a symbol of national sovereignty and

territorial integrity, and its members promised to give their lives to

defend him. They blamed corruption on the officials surrounding him and

warned fellow Moroccans of the dangers of foreign interference.

Still, the group could not prevent the

emergence in 2011 of the February 20 Youth Movement, which called for

greater freedom and social justice and demanded the introduction of a

parliamentary monarchy. The brief pro-democracy uprising paved the way for

the adoption of the 2011 constitution, which recognized Morocco as a

constitutional and parliamentary democratic monarchy. It also emphasized

the need for separate branches of government and making the wielders of

power accountable to judicial review. The constitution, however, was not

implemented in full and failed to bring the kind of democratic transition

its proponents were hoping for.

The Amazigh Question

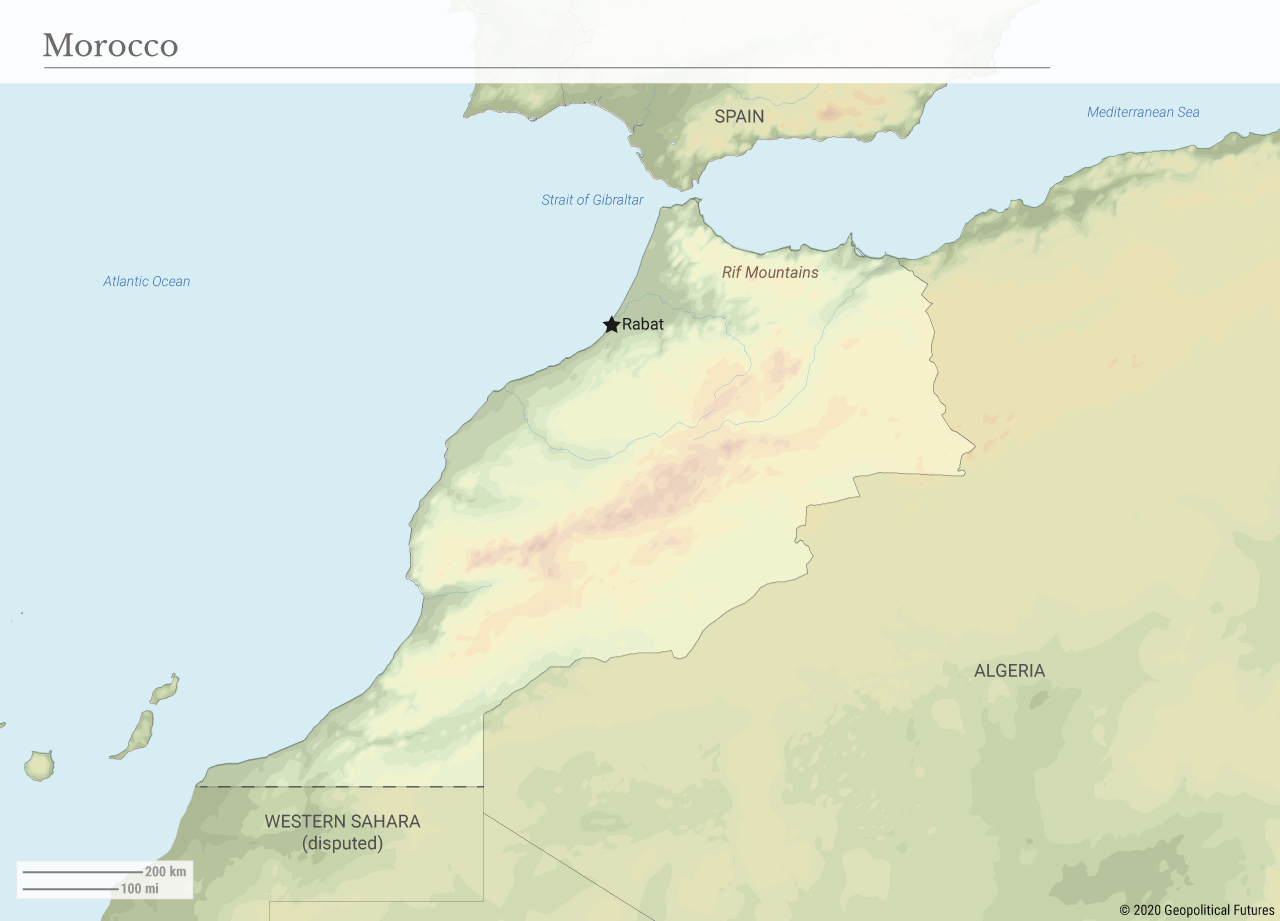

Another challenge for modern-day

Morocco is how to integrate the Amazigh, or Berber, ethnic group. The

majority of Amazigh live in northern Morocco, in a region called the Rif. In the 1920s, Abd el-Krim, an iconic Amazigh leader, fought French and

Spanish colonial forces and founded the Republic of the Rif (1921-26). The

Amazigh waged the Taflilat revolt in 1957, and Rif wars continued until

1959.

(click to enlarge)

Inspired by the Amazigh in Algeria, the

Amazigh in Morocco demanded political integration, cultural recognition and

economic development for their communities. But Hassan played a crucial

role in suppressing the Amazigh, and in a 1984 speech in the Rif in

northern Morocco, he described them as bandits, cannabis cultivators and

smugglers and warned them against campaigning for greater autonomy.

Mohammed VI expressed genuine interest

in integrating the Amazigh as long as he did not have to make political

concessions. He created the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture, made

Amazigh an official language on par with Arabic and opened a Tamazight TV

station. However, little progress has been made on economic development. In

2016, peaceful protests erupted in the Rif region after an Amazigh

fisherman in al-Hoceima, a city on the Mediterranean coast, tried to

retrieve his fish that the authorities had dumped into a garbage truck. The

protests were led by activist Nasser Zefzafi, who was arrested on charges

of threatening national security and given a 20-year prison sentence. Today, thanks to its rugged terrain, the Rif region maintains a de facto

semiautonomous status largely outside the control of the state, except when

the government decides to launch punitive military campaigns.

Future Prospects

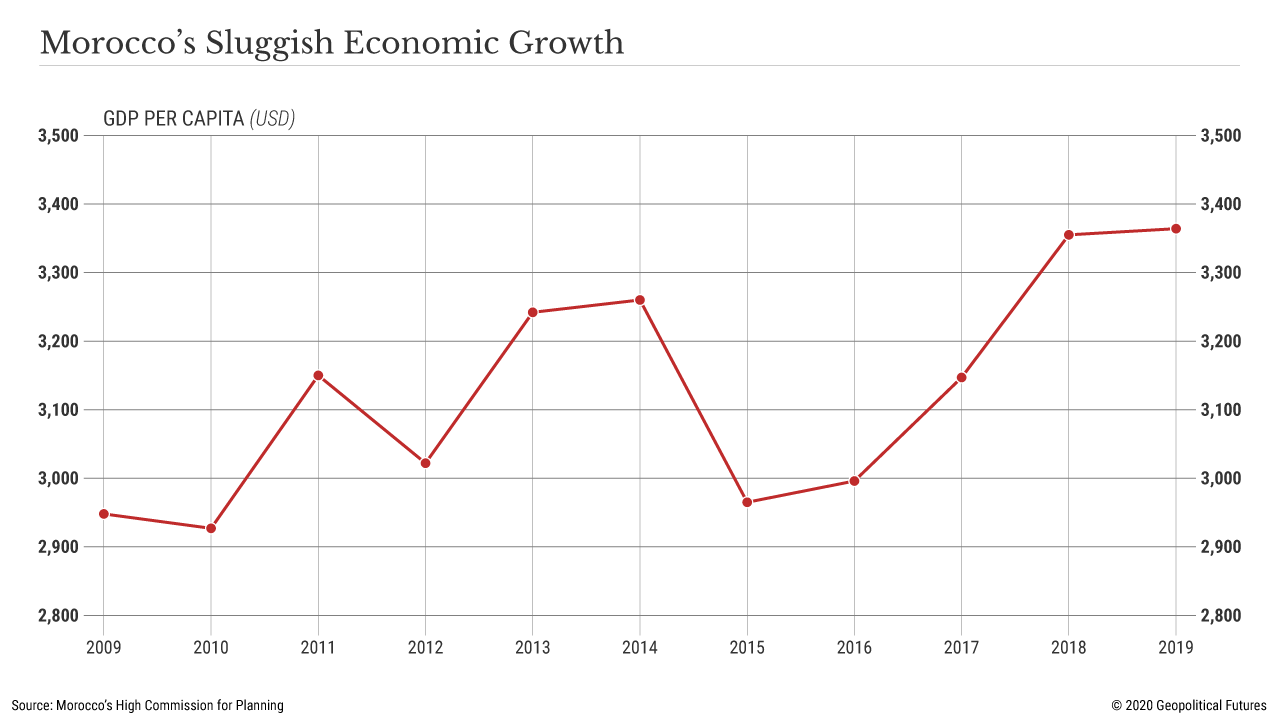

Morocco’s progress has been limited in

terms of both political reforms and economic development. Mohammed VI has

not followed through on his promise to introduce political changes. The

king’s supporters say that Morocco will become a parliamentary monarchy if

and when capable political parties and a responsible civil society emerge.

But they also note that it took Britain centuries to institute its

constitutional monarchy and argue that Morocco’s history, its demographics

and regional conflicts mean that the transition will take time. Meanwhile,

Moroccan law still does not allow a single party to win an absolute

majority in the House of Representatives. The king remains in full control,

and parliament is essentially a rubber stamp for the monarch that merely

approves the Cabinet’s bills. The king keeps parties on a tight leash and a

close eye on nongovernmental organizations.

In 2002, 26 political parties ran in

the general election. The top vote-getter, the Socialist Union of Popular

Forces, won just 12 percent of the assembly’s then 325 seats. Instead of

appointing the party's leader, Abderrahmane Youssoufi, as head of the new

government, the king designated Driss Jettou, an independent lawmaker, as the

new prime minister. In the 2016 election, 27 political parties participated

and 15 did not win a single seat. The Justice and Development Party, led by

Abdelilah Benkirane, came in first place with 125 seats, while the

Authenticity Party came in second with 23 seats. After Benkirane failed to

form a Cabinet, the king appointed former Minister of Foreign Affairs

Saadeddine El Othmani as prime minister.

In addition, many of the social reforms

that Mohammed VI introduced after he assumed the throne were not properly

implemented. Changes to the civil code, for example, apply only in theory,

as polygamy and child marriage are still common. The promise of economic

development has given way to stagnation because of bureaucratic lethargy

and poor governance. Public debt exceeds $77 billion, more than 83 percent

of gross domestic product, limiting investment in development projects.

With a per capita income of $3,400, Morocco is the fourth-poorest Arab

country.

(click to enlarge)

Morocco failed to industrialize, and

with economic growth in 2019 at 0.3 percent, it no longer attracts foreign

investors. Several years of drought have weakened the agricultural sector,

and the COVID-19 pandemic has introduced even more hurdles. These

challenges prove that Morocco needs to adopt a new way of thinking about

political and economic development.

|

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario