Ankara’s aspirations go far beyond its capabilities.

By: Caroline D. Rose

It seems that in every corner of the Middle East, Turkey has inserted itself in one way or another. In northern Iraq and Syria, it’s trying to establish buffer zones to prevent insurgents from penetrating its border. In the Caucasus, it’s trying to protect vital energy supply chains and counter Russian influence.

In Somalia and Qatar, it operates shared bases and provides military training programs to maintain a foothold in the Horn of Africa and in the Gulf. And in the Black Sea, where it recently discovered significant natural gas reserves, it will be increasingly assertive to protect its access resources.

Yet for Turkey, the most vital theater is the Eastern Mediterranean. It has become the focus of Turkish energy interests, mercantile opportunities and an emerging, forward-leaning defense posture that not only protects existing Turkish interests but expands them.

Turkey’s corresponding naval buildup is ambitious. It has invested significant political capital in establishing a greater Mediterranean foothold – using drilling operations off the coasts of Cyprus and Greek islets, intrusion in conflicts like Libya’s civil war, and gunboat diplomacy against regional rivals to “reclaim” its maritime dominance.

Still, Turkey’s immediate focus is closer to home: deterring conventional threats along its Mediterranean coastline.

Operational constraints in the southern Mediterranean, logistical challenges, economic and defense limitations, and rising conventional threats will ensure that for now Turkey remains focused on its own backyard, not the dominant Mediterranean power it claims to be.

Turkey’s Vision

It would be an understatement to say that Turkey’s defense posture looks drastically different than it did just a few decades ago.

Until the 1990s, Turkey’s inward focus on its economy, political modernization and infrastructural development, combined with the looming threat of the Soviet Union and its own loyalty to NATO, compelled it to follow a foreign policy based on deterrence rather than expansionism.

But in the 1990s, Turkey and the West began to drift apart. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Russian threat waned, as did the interests shared between Turkey and the West.

Ankara’s military leadership adopted a “two and one-half war strategy” – the idea that it should be prepared to wage two wars, one to its east and one to its west, simultaneously, while also fighting an ongoing, unconventional “half war” with Kurdish insurgents at home.

The strategy essentially saw Turkey’s location, wedged between the Black and Mediterranean seas, as a vulnerability.

In the 21st century, Turkey began to adopt a more independent, assertive military doctrine.

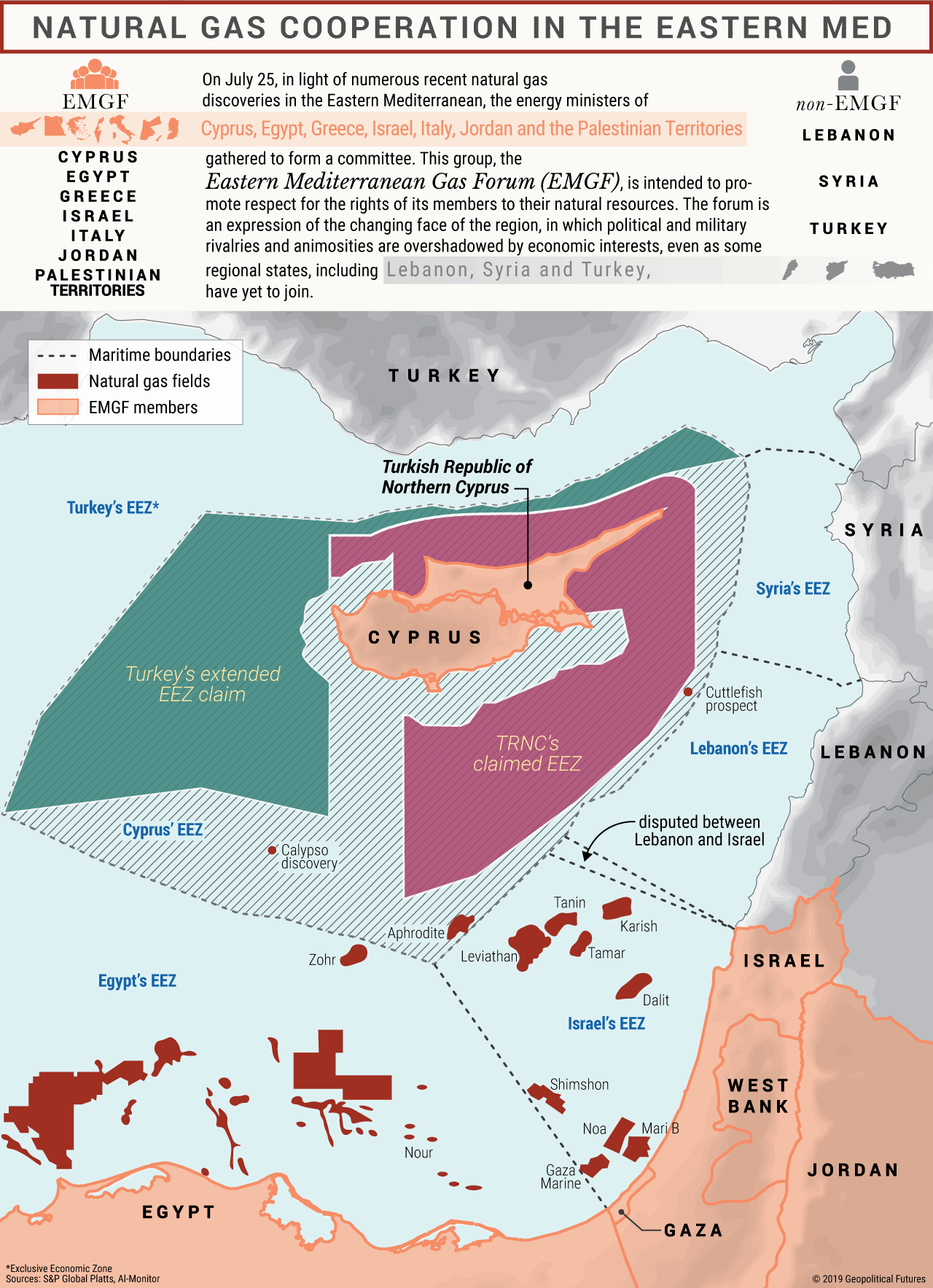

The discovery of hydrocarbons in Turkey’s periphery piqued Ankara’s interest, particularly as it struggled to diversify its natural gas suppliers, and it needed a navy that could help defend its claim over them.

It continued to drift away from the West as Brussels walked back its commitment to Turkish membership in the European Union and as it continued to butt heads with its NATO allies.

The re-emergence of the Russian threat, an increasingly aggressive Iran and a growing anti-Turkey coalition in the Mediterranean further isolated Ankara.

So it introduced the concept of Mavi Vatan, or Blue Homeland, which has dominated strategic thinking among Turkey’s military brass and nationalist politicians.

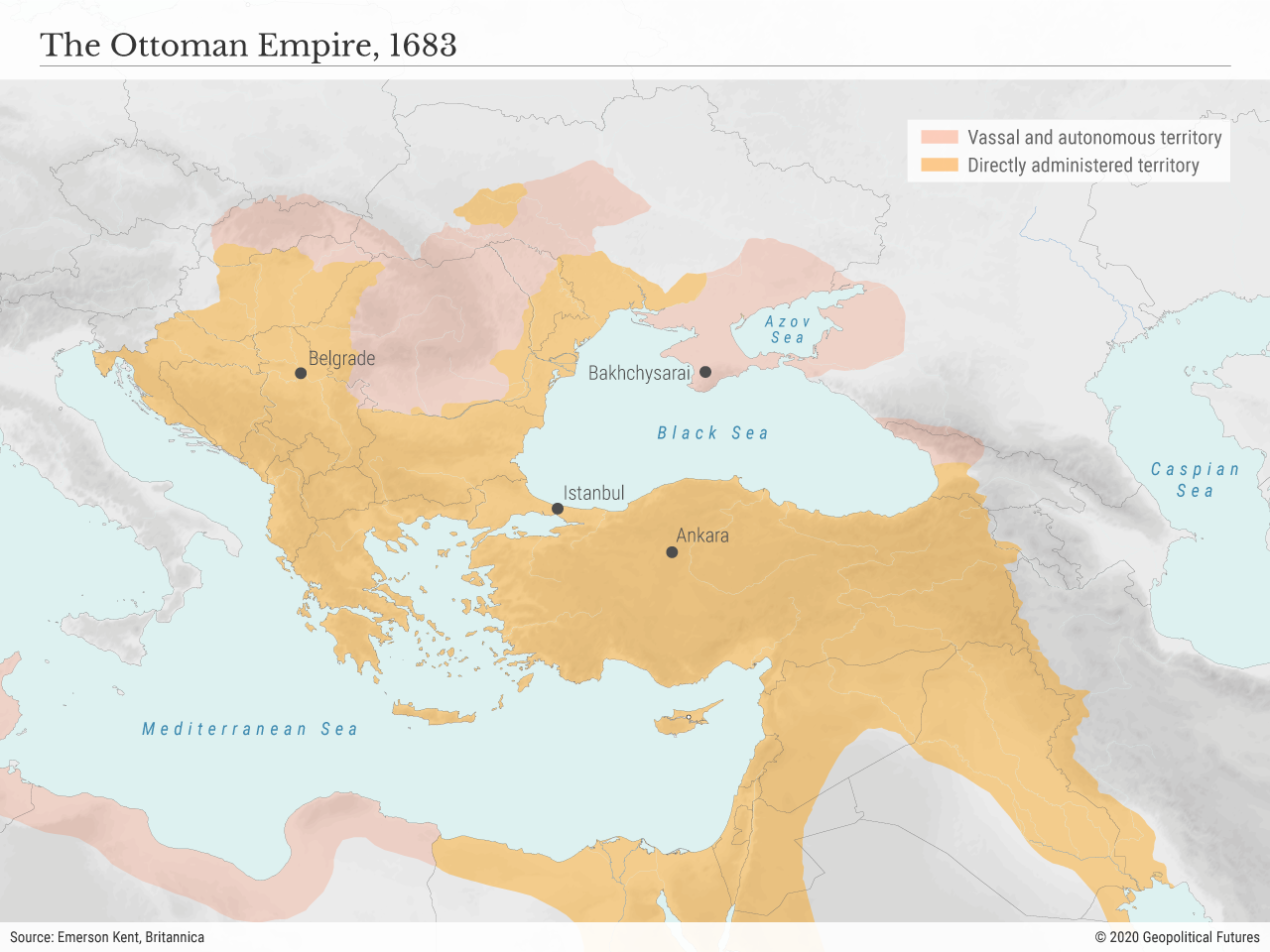

The concept asserts that Turkey should work to dominate the Mediterranean and reclaim the mercantile and maritime supremacy that the Ottomans once had.

Essentially, it advocates that Turkey’s location isn’t a vulnerability – it’s an asset that gives the country strategic depth.

The purpose of the strategy is not just to expand Turkish influence abroad but also to fulfill many of Turkey’s domestic and financial imperatives.

Having a strong naval presence in the Eastern Mediterranean allows Turkey to assert claims to oil and gas reserves in contested waters there – which may help Ankara eventually achieve energy independence and even become an energy hub.

Boosting Turkey’s own defense industry to reduce its reliance arms imports, which often come with strings attached, is a key component of the domestic agenda of the ruling Justice and Development Party.

Investment in indigenous defense manufacturing has introduced a wave of new financial opportunities for the struggling Turkish economy and has increased Turkey’s prestige abroad.

Turkey’s military spending has thus skyrocketed since the 1990s. It went from being the third-largest arms importer to the 14th-largest arms exporter. The country has reduced its arms imports by 48 percent since 2015 and increased its defense budget by 86 percent in the past decade.

Turkey has also launched the highly publicized MILGEM program that will roll out indigenously built corvettes and frigates, Type-214 air independent power submarines and MILDEN attack submarines, as well as torpedoes, missiles and sensory equipment.

It also announced that it will build 24 vessels (four of which are MILGEM frigates) by the Turkish Republic’s 100th anniversary in 2023.

Turkey’s Limitations

Despite these advancements, Turkey’s naval capabilities are still limited. While it’s laying the groundwork to have a navy capable of projecting power by the 2030s and 2040s, its current operational capabilities can’t extend much beyond the Aegean and the southern Mediterranean.

Moreover, though Turkey’s navy is larger than that of its main rival, Greece, there are several other Mediterranean nations with which it must contend Increased patrols and joint maritime exercises involving Greece, France, Italy, Egypt and even Israel have raised the stakes for conventional conflict.

If Turkey poses a serious threat to Greece – say, by violating the partition in Cyprus or attempting to invade Crete – it will have to face a coalition of capable naval forces with substantial combined firepower that would overwhelm Turkey’s own.

Most of Turkey’s naval projects are years – or even decades – away from being operational.

Chief among them is its first amphibious assault ship, the TCG Anadolu, which is expected to be completed by the end of this year. The Anadolu is designed to serve as both a light aircraft carrier and a command center in the Mediterranean.

It can sustain combat missions at farther distances by carrying 14 STOVL fighter jets or heavy-lift helicopters, several amphibious assault vehicles, 29 main battle tanks, and four mechanized, two air-cushioned and two personnel landing vehicles.

With the ability to carry out an amphibious invasion, it would a threat to the sovereignty of small Aegean islands near Turkey’s coast. It could also aid Turkey’s operations in Libya, allowing for quicker reinforcements, deployment of more equipment for mechanized infantry units and greater airpower projection.

On paper, the TCG Andalou appears to close at least some of the gap in Turkey’s Mediterranean capabilities. But the ship alone won’t give Turkey an edge over the combined forces of France, Egypt, Greece and Israel.

The new fleet of locally built ships will assist Turkey’s strategy of defending its perimeter by applying pressure deeper into the Mediterranean, creating new maritime buffers and strengthening its bargaining position against regional rivals.

But over the next decade, it will still have to rely mainly on gunboat diplomacy to achieve its defense objectives. Its focus will remain on its littoral waters and projecting power over weaker actors, like Libya and Cyprus and certain Aegean islands.

This explains why Turkey’s arsenal doesn’t include a destroyer but does include a growing number of frigates and corvettes that can sail between critical sea lanes and islands in shallow waters.

Until Turkey can secure forward bases and a more powerful maritime fleet, its entire defense strategy will struggle to overcome logistical, refueling and funding constraints. Turkey still faces challenges in equipping enough fuel tankers with an escort fleet that can resupply its vessels, aircraft and patrol boats that venture beyond the Aegean. One light carrier can’t do the job on its own.

Moreover, production delays due to COVID-19 and Turkey’s sluggish economy have raised questions over whether Turkey can complete projects on time, let alone begin production on a second planned assault carrier, the TCG Trakya. Its economic woes have also led to slower growth in Turkey’s defense budget since the country’s 2018 recession.

And although the runways of the TCG Anadolu and TCG Trakya have been reportedly designed to also accommodate F-35B Lightning-II jets, Turkey may not even acquire these aircraft given the U.S. decision to cut it out of the F-35 program.

Ankara could theoretically acquire comparable aircraft from the U.K., Spain and Italy, but Europe would be reluctant to arm Turkey with fighter jets that could be used to intimidate other Mediterranean states.

Turkey has been juggling its defense priorities in the Levant, Caucasus, Black Sea, Gulf and Red Sea, but it’s now zeroing in on the Eastern Mediterranean, where it hopes to create the impression that it has an operational edge over its regional rivals.

But while it incrementally builds up its naval capabilities, its focus will remain on coastal defense – no matter how much it touts its Blue Homeland aspirations.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario