Any move by the West will likely tip the scales in Moscow’s favor.

By: Ekaterina Zolotova

Let’s take stock of the situation in Belarus. Two weeks ago, Alexander Lukashenko was reelected president in what is widely considered a sham election. Violent protests began immediately thereafter, with laborers later striking and joining the fray, demanding Lukashenko's resignation. Opposition leader Svetlana Tikhanovskaya left Belarus for Lithuania as soon as the results were in and has since formed a coordination group for the transfer of political power.

Russia and China congratulated Lukashenko on his victory, while Poland, the Baltic states and other Western countries rejected it. The European Union said it does not recognize the election results and will impose sanctions on those involved in electoral fraud and voter suppression. The U.S. is considering similar measures.

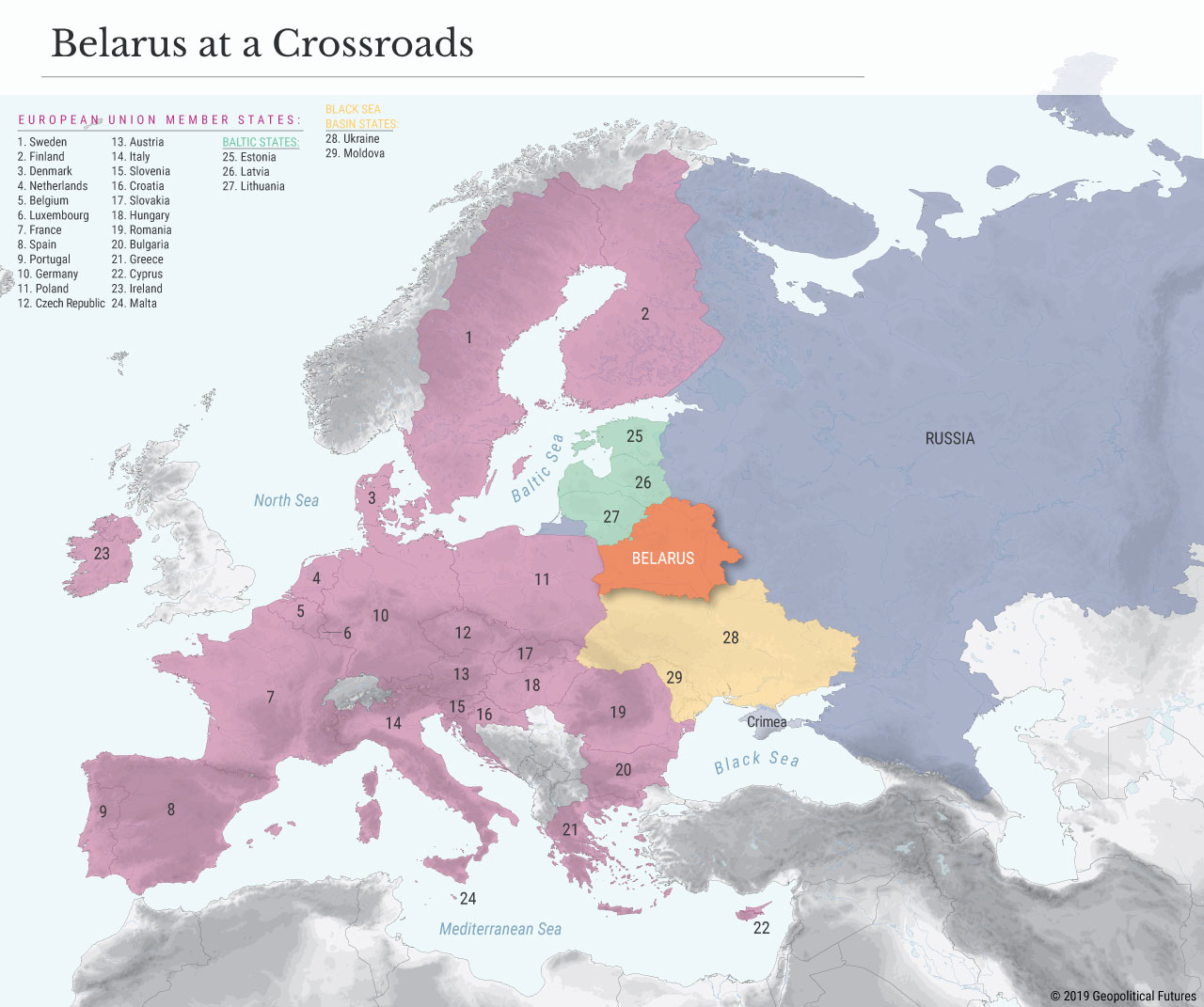

Put simply, everyone is worried about Belarus, a strategically important country sandwiched between Russia and Europe that serves as an important transit zone and insulates Russian troops from American troops permanently stationed in Poland. A shakeup there could alter the balance of power in the region, but so far no one seems willing or able to put much at risk to resolve the conflict themselves.

Tipping the Scales

Which is not to say they have been doing nothing. Reportedly, Poland and Lithuania have been especially supportive of the Belarusian opposition. Poland’s interests in doing so are straightforward: geographical, historical and cultural proximity – in fact, what is now Belarus was once part of Poland – as well as a desire to become the dominant power in Eastern Europe and protect itself against Russia. Lithuania’s interests are similar; it’s trying to strengthen its role as a regional leader and become representative of the interests of the EU and NATO in the East. (It, too, remembers a time when it was a much larger power that controlled parts of Belarus.)

It’s little wonder that the two have long worked against the current Belarusian government, which tries to balance between Russia and the West but is much more beholden to Russia. So when they can, Belarus’ neighbors try to tip the scales in the West’s favor. Just before the presidential election in 2006, for example, Lithuania’s president warned that Belarus could attack the country, even as Belarusian intelligence announced the discovery of bases of political opponents allegedly intent on disrupting the election.

In the past, Minsk has also accused the Polish Embassy in Belarus of gathering information about the organization of ethnic Poles in Belarus and interfering in its affairs.

This year, Belarusian media reported that many of Lukashenko’s political opponents passed through Poland. It’s not proven that Poland and Lithuania did any of the things they have been accused of, but given their interests it’s plausible they did.

Yet, there’s only so much they can do, since they’re too weak to replace Russian influence in Belarus on their own. For that, they’d need the help of the EU, which they have tried to recruit to the effort by focusing on the threat of expanding Russia’s domain into their sphere of influence. (Many of the bloc's members, including Germany, value their bilateral ties with Russia too much to break things off.)

This time, though, they are trying to be recognized as mediators, which Brussels is unlikely to grant. If it doesn’t, they may be forced to turn to the U.S. for help. And though Lukashenko has certainly accused the U.S. of organizing some of the ongoing protests, Washington actually has no reason to provoke a conflict with Moscow. Its security interest is in the stability of Poland, so there’s no need for it to make a rash decision in Belarus.

Nothing New

The EU, meanwhile, has always been wary of Belarus, which it saw as a Russian stooge. But as with so many other issues, the EU was divided on Belarus.

The split is explained largely by geographic proximity: Western European countries didn’t have particularly close ties with Belarus or Russia and thus didn’t show much interest in what happens in Minsk. Eastern European countries never had that luxury.

Germany, for example, has fairly close economic and political ties with Russia and is interested in Belarus as a stable transit zone, so it will not fully support Poland and Lithuania in their campaign against Belarus. And with the coronavirus crisis, economic recession and Brexit, the European Union doesn't really want to spend its resources to fight for democracy in Belarus anyway.

Its decision not to recognize the election results and levy sanctions, too, is less remarkable than it sounds. It’s the only thing it can do to show it cares without spoiling relations with Russia.

Nor is it new; it did the same thing in 2006, when protests erupted after Lukashenko won the presidency. After the 2010 election, the president of the European Parliament said Lukashenko’s victory was illegitimate. In the 2015 elections, the European Union actually recognized Lukashenko as the head of Belarus but did not invite the elected leader to European talks.

The newest sanctions are not yet in place, but when they go live, they will be directed against people who have already been under sanctions and know how to develop the country and maintain bilateral trade relations. In short, so long as Lukashenko remains in power, the EU knows how to deal with Belarus and Russia.

Russia Keeps Calm

Belarus is Russia’s only remaining ally to the west, and it is in the Kremlin’s interests to keep it stable without directly intervening. It will if it must, but it likely won’t have to, since Lukashenko still has the support of the military.

And it probably doesn’t want to. The conflict is a unique chance to improve Russia's position in Europe, especially when the slowing Russian economy is in such need of new sales markets and support for gas projects. The EU chose Russia as the main mediator of this conflict - German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron discussed the situation in Belarus with Russian President Vladimir Putin rather than with Lukashenko.

The Kremlin still has an option to give Lukashenko an offer he can't refuse. But Russia is in no hurry to do it alone; it is in its interests to establish joint efforts with the EU, if they’re so inclined. Russia can even agree to new elections, but only if the EU promises the Kremlin that the Russian position in Belarus will not change.

And that’s the key point. Russia can’t afford to lose its important buffer zone, so it absolutely wants to keep Belarus pro-Russian, or at least neutral. But the Kremlin is keeping calm; the sanctions imposed on Belarus mean relations with the EU will degrade at least a little and Russia will reap the benefits. (For example, if Lithuania refuses to supply goods to Belarus through its ports, Belarus can always find a way out through Russian ports.)

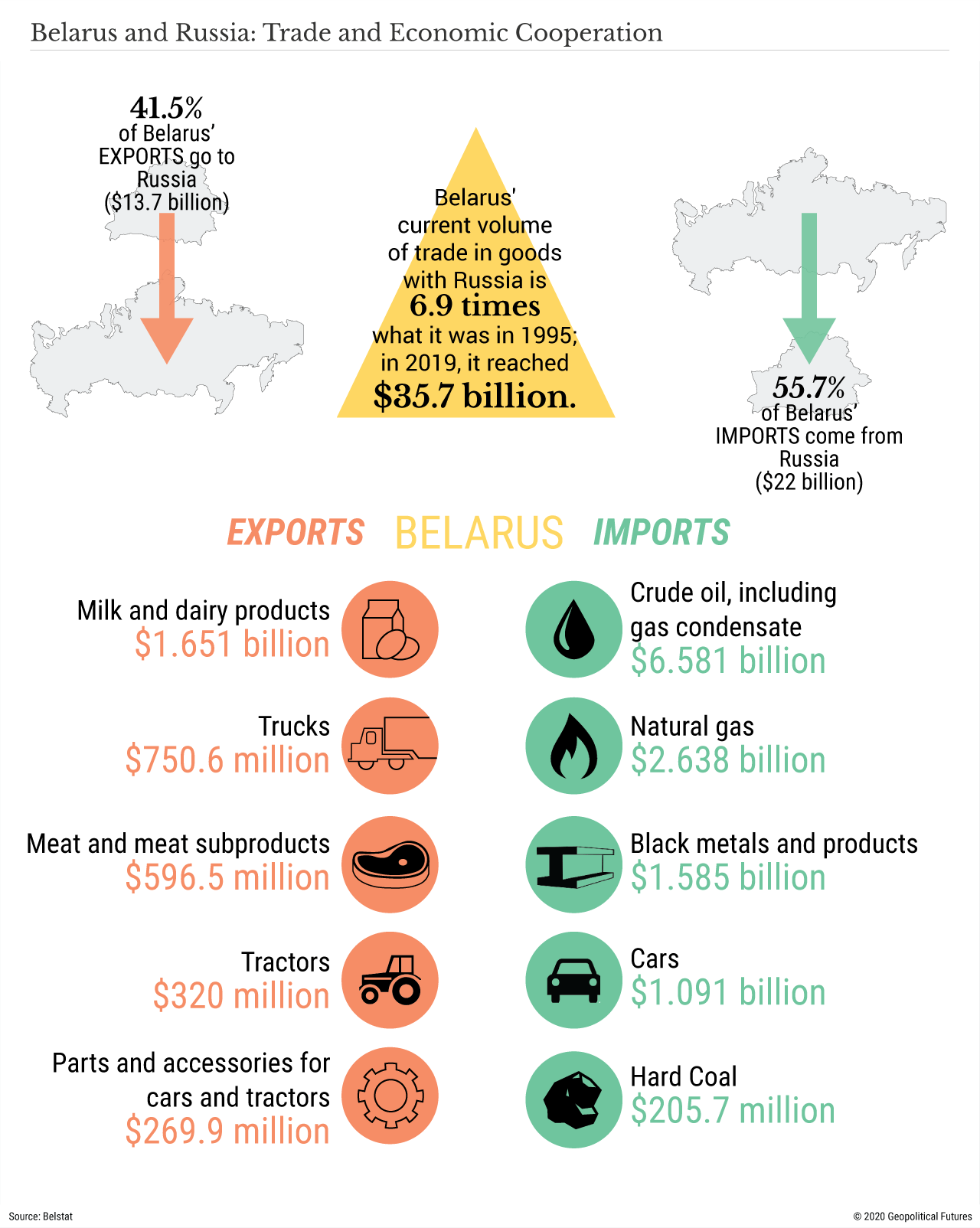

The good news for Moscow is that Belarus understands its limits. It knows its small economic potential could theoretically be exploited by Western states, and if it left Russia’s orbit, and thus leaves the Eurasian Economic Union, it could lose about a quarter of its gross domestic product.

Protests in Belarus may continue, but the president still has all the levers he needs to suppress unrest. He also understands that no country wants to have a second unstable country in the region. Russia may gradually move from the role of an observer to the role of an active player, who will be sympathetic to both the tired Belarusian public and the worried EU, which may only increase Russian influence in Belarus.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario