|

As the December 2020 deadline for a

negotiated trade deal approaches and the European Union and the United

Kingdom fail to get on the same page, a hard Brexit looks more and more

likely. In a no-deal scenario, British-EU trade would default to World

Trade Organization rules that would damage both economies by raising

tariffs, delaying international deliveries and so on. The EU is expected

to fare better than the U.K. Forecasts show that

British gross domestic product will drop by about 5 percent over 10

years, while the EU’s GDP will fall by a little less than 1 percent.

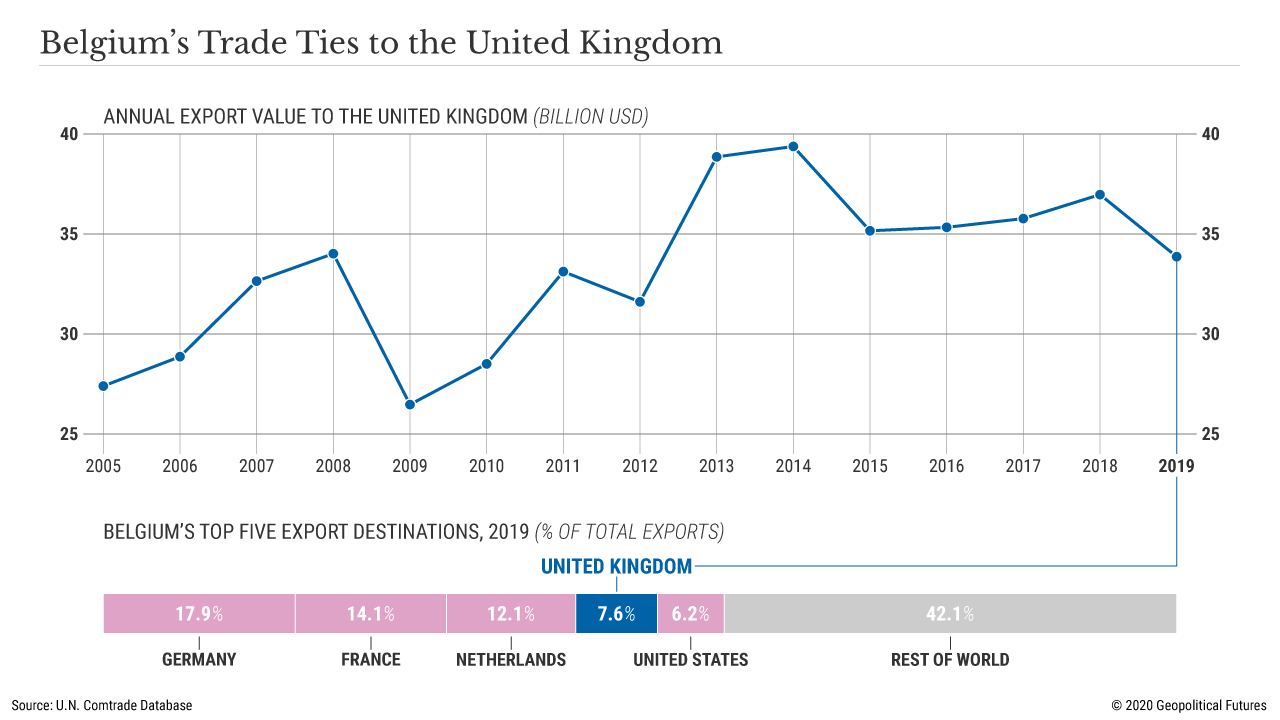

Yet, some EU members will be worse

off than others, none more so than the EU’s host country, Belgium. With some 8 percent of its

GDP relying on trade with the U.K., Belgium is uniquely

exposed to Brexit’s economic shockwaves. Naturally, there will be

domestic political consequences to the coming economic pain. The hit to

exports will unevenly affect Belgian regions, hitting the country’s

northern commercial hub, Flanders, the hardest, aggravating a political

rivalry shaded by separatist sentiment that has plagued Belgium for its

entire modern history.

Disparities

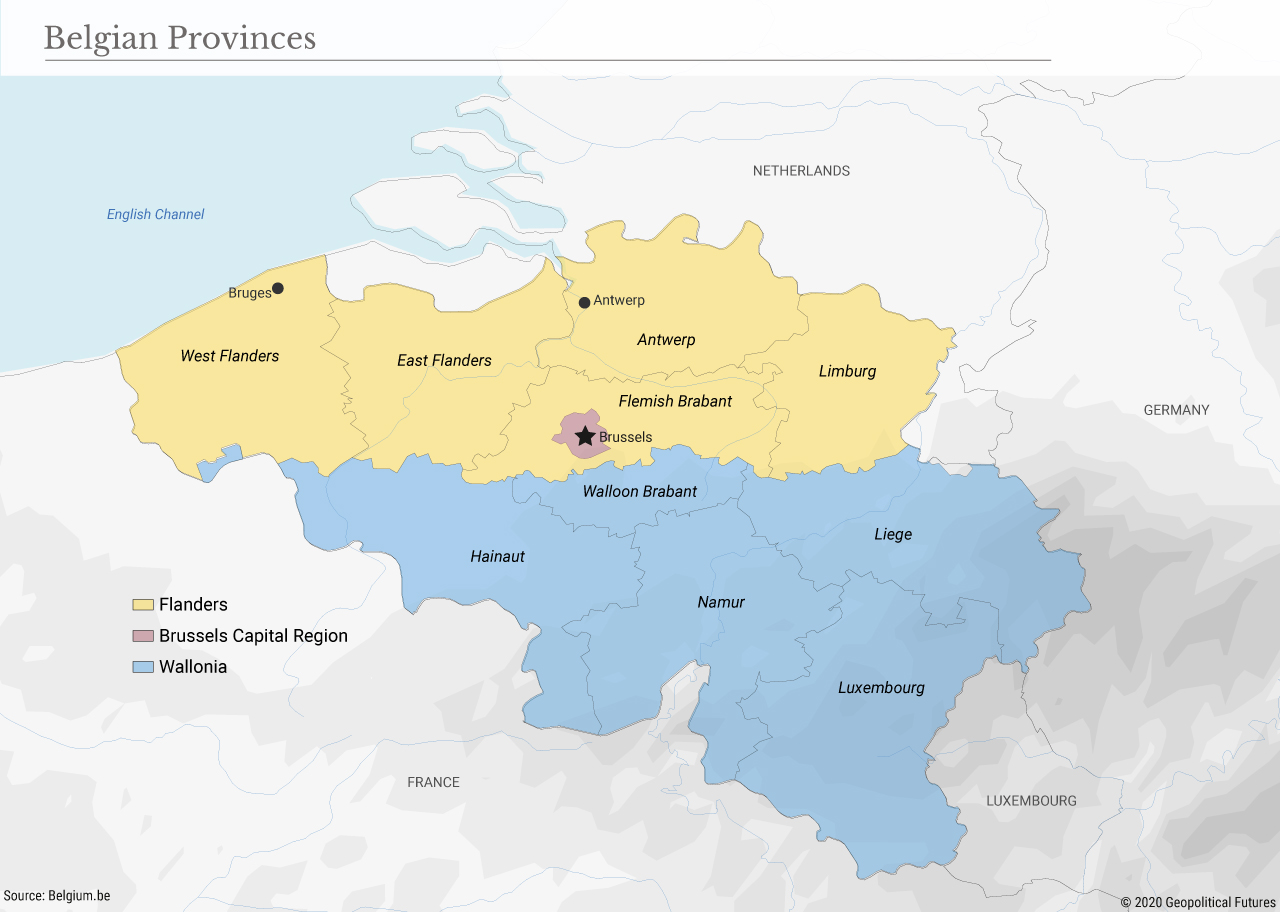

Belgium’s Dutch-speaking Flemish and

its French-speaking Walloons have been at loggerheads for centuries,

dating back to the country’s role as a buffer zone between the Napoleonic

and Dutch empires. It was not until 1830, when Belgium was a part of the

Kingdom of the Netherlands, that anti-Dutch sentiment led to revolution,

marking the nation’s independence and creating an internal divide –

punctuated by cultural, linguistic and religious differences – that endures today.

(click to enlarge)

Important as these differences may

be, Belgium’s present-day divide is defined by economic disparity. During

the 19th and early 20th centuries, Wallonia was the place to be. Although

it was half the size of Flanders, Wallonia was the site of Belgium’s

fast-growing coal and mining industry, bringing immense wealth to the

south, while its French-speaking population gave the region a reputation

of being an upper-class, bourgeoisie hub. This changed when coal began to

die out. Businesses and financial investment fled north to Flanders,

historically the commercial gateway to the English Channel and North Sea.

Flanders is home to ports in Antwerp and Bruges and is thus a modern hub

of international trade and Belgium’s economic engine, accounting for

roughly 60 percent of the country’s GDP. The north is also home to the

majority of Belgium’s industrial production, hosting a number of

factories and production centers for the petrochemical, textile and

technology industries. Flanders flourished as Wallonia fell behind,

giving way to notable disparities

in employment, education, exports and imports, and contributions to

national GDP.

The regions’ political attitudes

clearly reflect these economic disparities. The south, for example, has

increasingly called for higher taxes

on the north to correct the imbalance. Much of the north regards the

south as burdensome, giving way to demands to cut off the south or reduce

the federal government’s influence on taxation. This has breathed life

into many far-right political blocs such as the Vlaamse Volksbeweging,

Voorpost, Nationalistische Studentenvereniging and the New Flemish

Alliance, and into right-wing movements like the Schild & Vrienden,

which have called for greater independence from the federal government,

secession from Belgium and even reunification with the Netherlands.

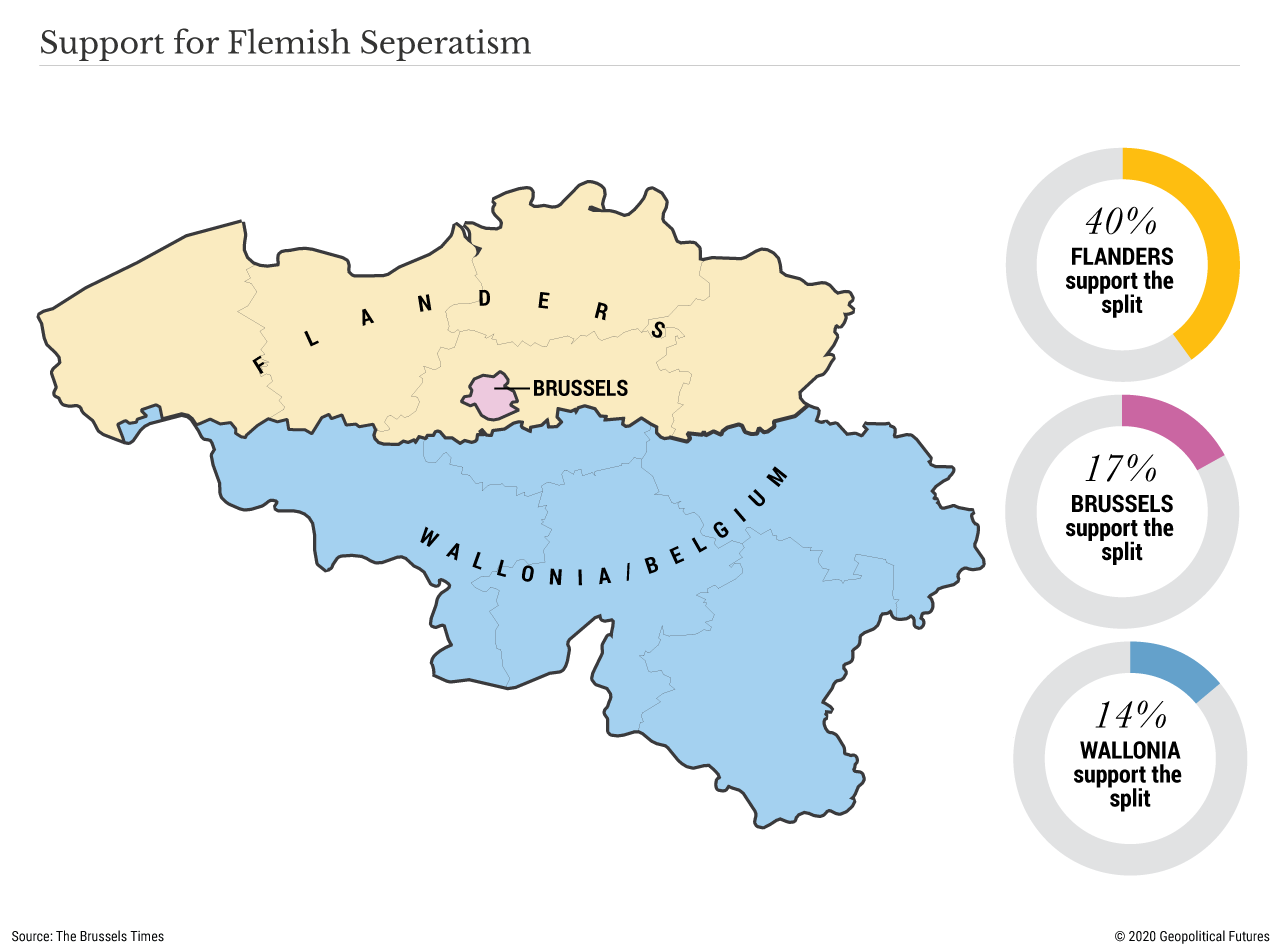

(click to enlarge)

Intense Debate

The 2008 economic crisis and the

COVID-19 pandemic have only made things worse. In May 2019, political

divisions were so bad that they created a 15-month stalemate on the

creation of a government that was temporarily solved only when parties elected a caretaker

prime minister, Sophie Wilmes, to manage the coronavirus

outbreak. The pandemic sparked an intense debate between northern and

southern Belgians. In hopes of keeping industries and businesses open,

Flanders wanted modest lockdown measures, while the south favored stricter measures and heftier

bailouts, a debate that sowed more seeds of resentment and

delayed the government response. Current estimates suggest that lockdown

measures will result in a 9 percent loss in GDP this year alone.

Brexit’s economic hit will only

exacerbate the divide. On Jan. 1, 2021, Belgium will be one of EU members

worst affected by the U.K.’s withdrawal from the European single market –

with the majority of the economic damage in the already-aggravated

Flemish north. Overall, Belgium’s national bank predicted that Brexit

would cost Belgium roughly 1 percent of its GDP, with the worst-case scenario

forecasting a 2.5 percent loss of purchasing power and nearly

28,000 jobs lost.

The damage, of course, will be felt

most acutely at first in Flanders, whose commercial advantages made it

more uniquely vulnerable to a hard Brexit. The region accounts for more

than 80 percent of Belgian exports to the U.K. and receives 87

percent of imports from the U.K. The largest sector in Flanders to be hit

will be the country’s petrochemical

hub, the world’s second-largest and Europe’s largest cluster,

which comprises 20 percent of Belgium’s total

exports to the U.K. As far as exports go, Brussels and the

French-speaking Wallonia are less exposed, home as they are to

less-important wood, glass and medical exports.

The Belgian government understood as

much and so tried to shield itself from the inevitable shock of the

U.K.’s departure from the single market. The country reduced its exports

– of minerals, pharmaceutical products and road transport materials – to

the U.K. by 12 percent by the second

quarter of 2019 (compared to the previous year), while

offsetting U.K. trade with increased trade among other EU members.

Moreover, the government began a campaign to attract U.K.-based investors

to open subsidiaries in Belgium to mitigate the damage to its services

sector.

(click to enlarge)

Importantly, most of these changes

disproportionately helped the south, where mineral production is

concentrated, and Brussels, an emerging financial and services hub. The

measures ultimately did very little to insulate Flanders from the shock

of Brexit.

Secession in the Cards?

Brexit will certainly reinforce

rising nationalist sentiment in Flanders, but it doesn’t necessarily mean

the north will secede anytime soon. While talks of secession have

increased, competing conservative parties in Flanders have created

political deadlock, and the majority of Flemish citizens are not fully on

board with the idea of secession. Polls conducted at the end of last year

revealed that just 40 percent of Flemish

Belgians support secession, down 6 percent from polls

taken in 2007. Many Flemish citizens understand that breaking

with Belgium could be economically harmful, much as it is in the U.K.,

since it would lose the benefits of Brussels’ financial centers and the

south’s agricultural imports. The costs of establishing a new state –

standing up armed forces, funding new institutions, etc. – would be daunting. This is

likely why Flemish parties have begun to try to hollow out Belgium’s

federal system, further devolving responsibilities to provincial

governments on issues such as transportation, health care, taxation and

governance.

On Jan. 1, 2021, the four-year Brexit

saga will be put to bed one way or another, and the U.K will depart the

European single market. When that finally happens, the EU will be able to

champion the example of a hard U.K. withdrawal as a cautionary tale to

euroskeptic movements. The negative impact on EU export hubs and the

effects of increased political gridlock, as is the case in Belgium, too,

will be a useful message against nationalist movements that call for

withdrawal from the EU, such as the “Italexit” movement pushed among

Italian far-right parties, as well as separatist movements in places like

Catalonia. The EU’s position is strengthened by the fact that divorce

from Brussels – for both the Flemish and euroskeptic countries – is just

too costly a venture. |

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario