For 200 years the two countries have partnered in mutually beneficial projects on a range of economic and security matters.

By: Cole Altom

Colombia is among the United States’ closest allies in the Western Hemisphere. For the past 200 years, the two countries have partnered in mutually beneficial projects on a range of economic and security matters. Any disagreements they’ve had were short-lived and relatively easily resolved. The key to understanding this unique and lasting partnership is understanding the role geography plays in their relationship.

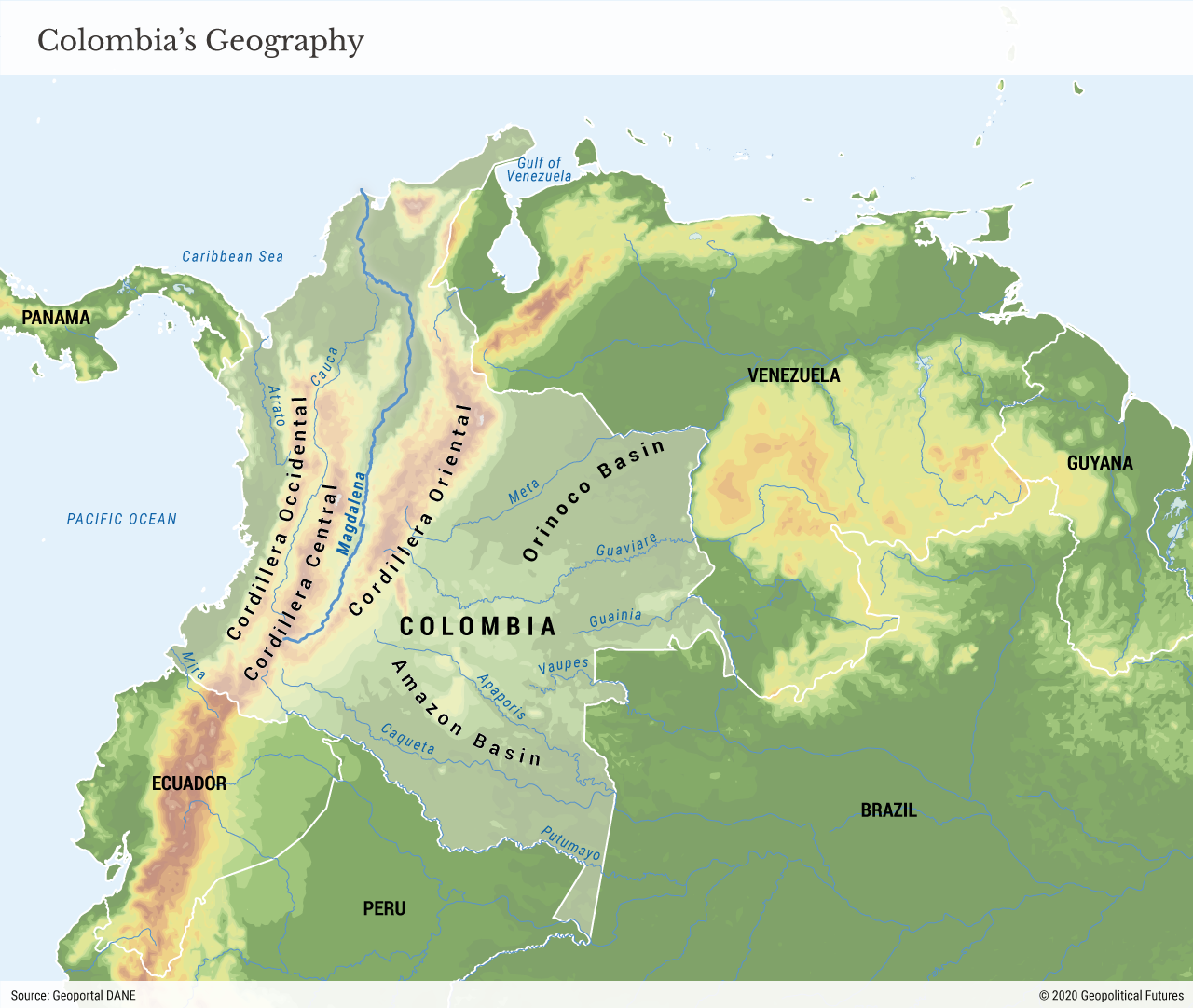

Located on the northern coast of South America, Colombia sits on the southern base of the Caribbean Basin. The Andes’ three distinct mountain ranges run the full length of the country, covering roughly half its territory. (The other half is composed of the Amazon and Orinoco basins.)

The mountains make east-west transport difficult and expensive, while the Amazon forest in the south discourages mass settlement and development. For this reason, Colombia’s population is concentrated in mountain valleys, in disconnected cities, and along rivers and the coast.

These disjointed parts of the country are integrated through the Magdalena River; indeed, it’s estimated that three-quarters of the population lives near this river or one of its tributaries, which also facilitate the transport of goods between the interior and the Caribbean port cities of Barranquilla and Cartagena.

Colombia has access to both the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans, and the construction of the Panama Canal only increased the value of its connection to both of the continent’s coasts.

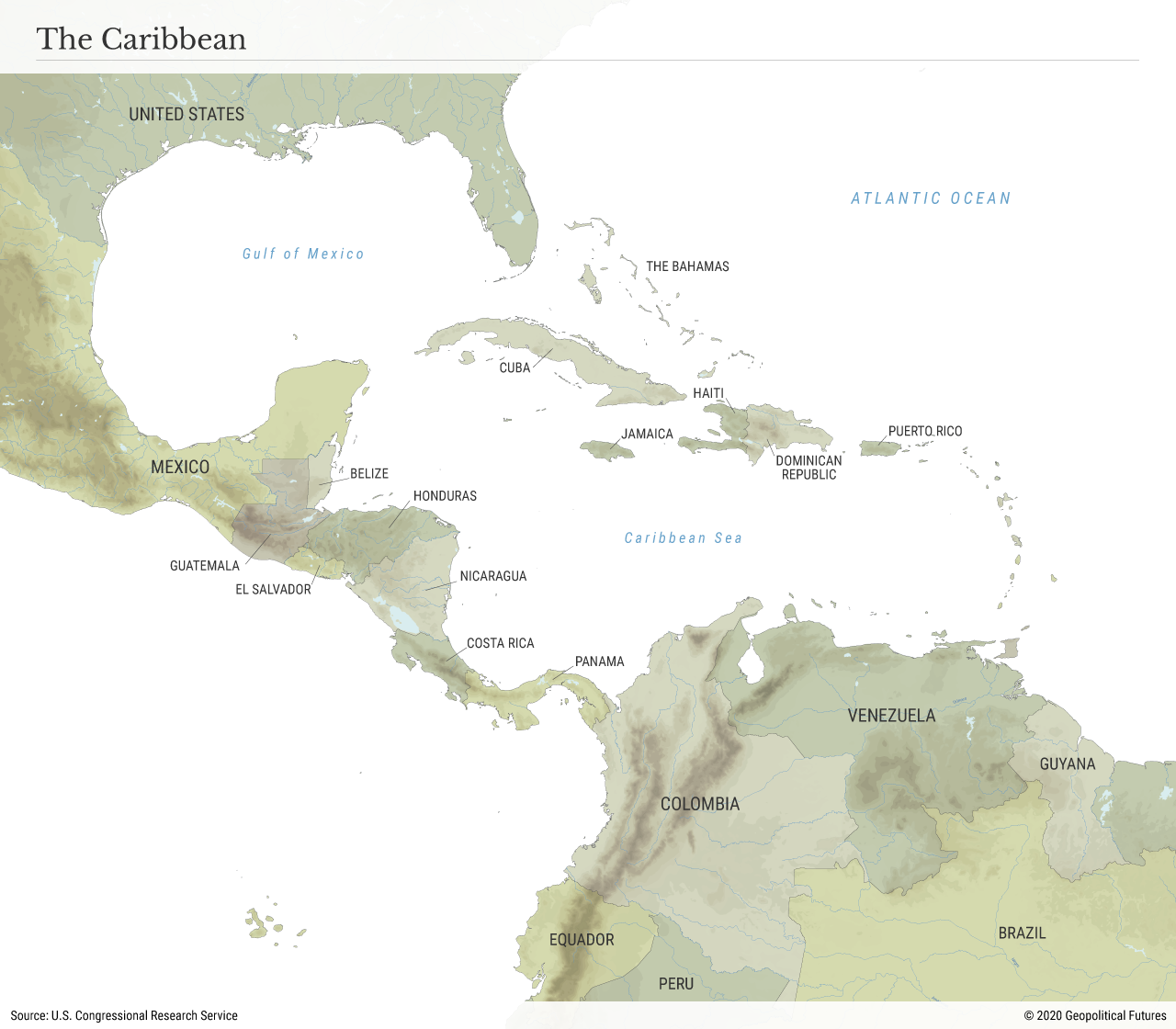

In the 1820s, Gran Colombia (composed of present-day Colombia, Panama, Venezuela and Ecuador) had the potential to dominate the region, as did Mexico and the United States. It dominated the Caribbean Basin’s southern rim and controlled the Isthmus of Panama as well as valuable sea lanes on the Atlantic, where much of the trade with Europe was conducted.

Mexico controlled the basin’s western coast, while the United States was well on its way to consolidating its control of the northern rim, having acquired New Orleans through the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and Florida in 1819. (The short-lived Republic of Central America, composed of present-day Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Mexico’s state of Chiapas was weak and fractured.)

However, Gran Colombia’s leadership potential slowly eroded after it experienced two strategically significant territorial losses. In 1830, Venezuela and Ecuador broke away to form their own countries. Gran Colombia thus lost control over a large portion of the Caribbean Basin and strategic depth on both its coasts.

Then, in 1903, Colombia lost control over the isthmus when Panama declared its independence.

During this time, the country also experienced frequent political unrest that forced the government to focus on domestic affairs rather than engage on global issues from a position of strength.

Colombia was therefore no longer positioned to dominate the southern Caribbean Basin. A weaker version of its former self, it needed to find a strong ally that could provide both economic and security support. It could look either to the north or to the south, but its geographic orientation dictated that a northern ally was the only real option. In the early 20th century, the Colombian government introduced its “respice polum,” or “look north,” doctrine, which called on the country to orient its foreign policy toward the north, particularly the United States.

Later, the “respice similia” doctrine emerged, advocating that Colombia adopt a more horizontal approach to foreign relations, with a greater focus on South America. Even so, Colombia has largely followed the respice polum doctrine.

The few instances where it aligned with other countries ended quickly as they offered Colombia limited benefit.

Even before the downfall of Gran Colombia, however, circumstances were pushing the United States and what would become Colombia together.

In the first half of the 19th century, the U.S. and Colombia wanted to reduce the influence of European powers, namely the United Kingdom and Spain, in the Western Hemisphere. From this emerged the first treaty the United States ever signed with another country in the Americas: the 1824 General Convention of Peace, Amity, Navigation, and Commerce, also known as the Anderson-Gual Treaty.

The treaty expired after 12 years, but an updated version that also ensured trade and mutual development was signed in 1846.

Decades later, another opportunity for cooperation arose. As a bicoastal country, the United States had long wanted to construct a transoceanic canal. In the 1870s it established the Interoceanic Canal Commission, which supported building a canal, and ultimately decided that Panama – then still part of Colombia – was the most practical site for the project.

France had already tried to build a canal through Panama in the 1880s but abandoned the effort, which had proved immensely costly in terms of both money and lives.

Initially, in 1902-03, the United States tried to establish a contract with Colombia to take up construction of the canal. But an eleventh-hour decision in Colombia not to ratify the deal led the U.S. to support Panama’s movement to gain independence from Colombia.

But the rupture could not last. Colombia needed secure access to the canal to access its western coasts, and the United States did not want to make a permanent enemy of a large country that could threaten the canal and influence sea lane approaches.

Washington also could not risk Colombia's partnering with another great power. What followed was the Thomson-Urrutia Treaty of 1921, which restored bilateral ties.

The treaty permitted Colombia to transport military equipment and troops, agricultural goods and industrial supplies through the canal free of charge. In exchange, Colombia recognized the borders and independence of Panama.

The United States also paid Colombia $25 million (approximately $350 million today) in damages, which was used to industrialize and improve infrastructure throughout the country. The United States benefited from this investment, since it helped drive out competing and still formidable British investment.

Since this reconciliation, U.S.-Colombian relations have continued largely intact. In the 1930s, Colombia fought a brief war with Peru and faced credit problems, which forced it to invite in U.S. companies to develop its oil resources.

During World War II, Colombia’s alignment with the United States helped keep its immediate surroundings and the canal secure. During the Cold War, the Colombian government often sided with the United States and rejected Soviet influence.

In exchange, Washington increased security and intelligence cooperation with Bogota and funded development programs through the Alliance for Progress. The timing coincided with Colombia’s recovery from a decade-long civil war known as "La Violencia."

Relations dipped in the 1970s following a decade of political violence in Colombia and growing disenchantment with the U.S. partnership, but the emergence of drug cartels and other domestic militant groups pushed Bogota to seek greater security support and cooperation from Washington.

As Colombia’s domestic situation stabilized over the 21st century, it came to play a greater role in regional security efforts, such as offering anti-narcotics training, and it is a political leader against anti-American regimes in the region.

More recently, the head of the U.S. National Security Council announced this week an investment plan worth $5 billion over three years focused on the rural development of Colombia. Though Colombia is the direct beneficiary, the goal of rural development is to curb coca production and reduce the presence and influence of criminal gangs throughout the countryside.

These groups support the region’s drug trade, which props up the government of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and creates security risks along the U.S. border and within the United States. More ambitiously, there is talk that such investment lays the foundation for moving U.S. companies from China and closer to the United States and other friendly territories.

Even now, economic and security interests, as well as the dangers of faraway powers, support the long-standing and mutually beneficial relationship between Colombia and the United States.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario