Turkey's Defense Industry and the Projection of Regional Power

A history of mistrust compels Turkey to fend for itself.

By: Hilal Khashan

Turkey’s relations with the West have never been smooth, not even when it adopted secularism and became a member of NATO. This has had a profound effect on the country’s defense industry. A history of arms embargoes and, alternatively, vast supplies of sophisticated weaponry convinced Ankara that it needed to fend for itself.

Indeed, when the West imposed an embargo after Turkey invaded Cyprus in 1974, Ankara established the Turkish Armed Forces Foundation, a significant enterprise that coordinates the activities of 14 arms manufacturers.

It’s been busy ever since. In 1975, the Turkish Armed Forces Foundation established the Aselsan Corporation to meet the country’s rapidly expanding military electronic needs, such as advanced automated systems, guidance, electro-optics, communication and information technologies. Roketsan, which specializes in missile launchers and sea defense systems, was founded in 1988 and is Turkey’s leading defense contractor.

In 2007, Turkish Aerospace Industries, in collaboration with British AgustaWestland, launched the T-129 helicopter project. The government also established the Presidency of Defense Industries in 1985 to oversee the country’s defense needs and ensure national security.

It’s now under the Office of the President. Since President Recep Tayyip Erdogan assumed power in 2003, domestically made military equipment rose from 20 percent to 70 percent.

The plan is for Turkey to become self-sufficient in providing for its military hardware needs and independent from external pressure by 2053. And since the country boasts some first-class manufacturers, it may well be able to.

Inherent Fragility

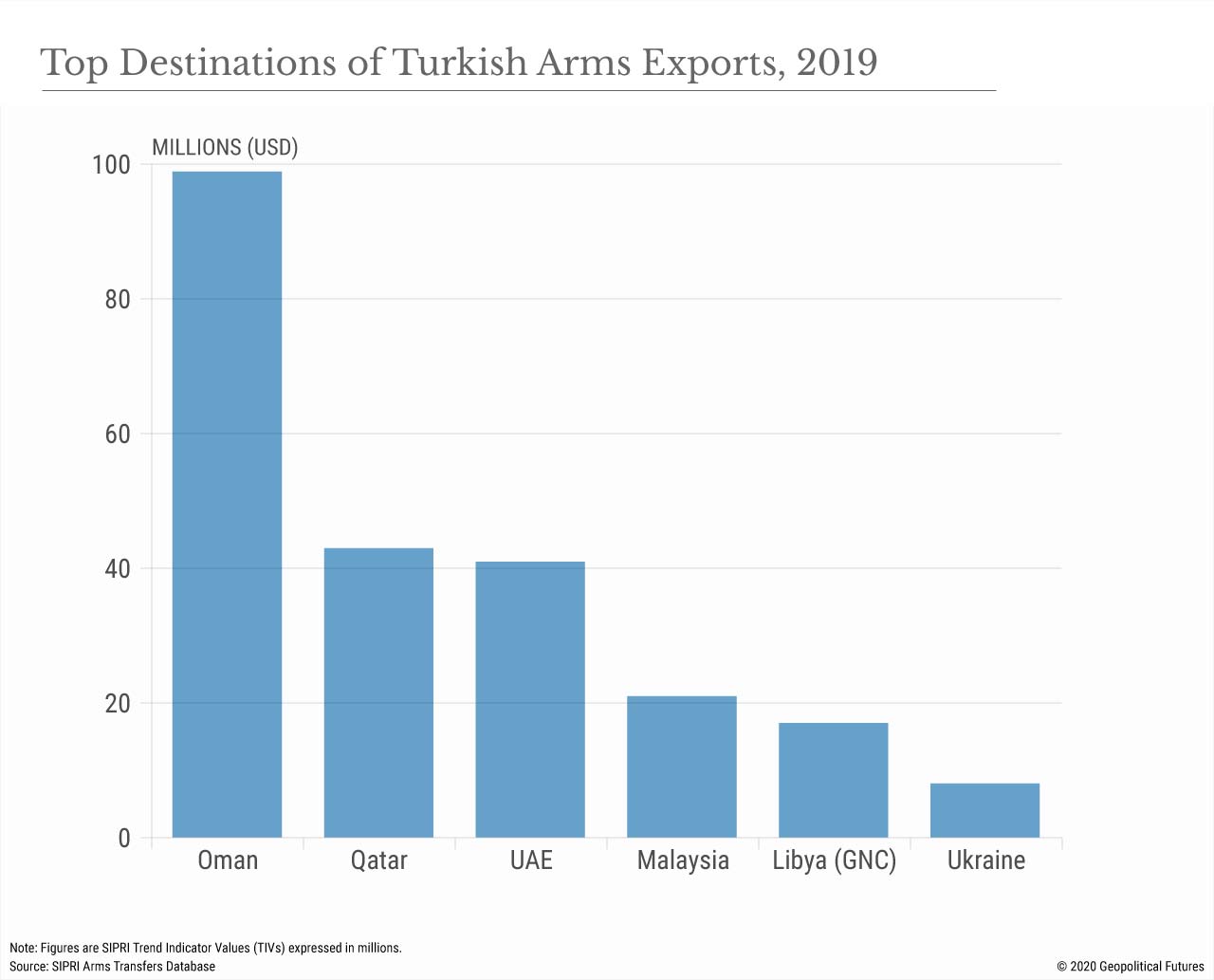

Turkey is the 14th-largest arms exporter in the world and accounts for 1 percent of total global military exports. It exports mainly wheeled armored vehicles, attack helicopters, howitzers, unmanned aerial vehicles and frigates.

It has a fixed customer base in majority-Muslim countries like Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Indonesia, Malaysia and Oman. (Poor relations with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates deny Turkey even more lucrative Muslim markets.)

Its sales to Guatemala, Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago are insignificant, and except for minor sales to the U.S., Germany and the Netherlands, NATO countries tend to not buy Turkish military hardware. Even so, Turkey believes its military exports will bring in (a very optimistic) $25 billion in 2023.

The future of Turkey’s defense industry hinges on the success of its domestic tank and fighter jet projects. The tank is manufactured with technical assistance from South Korean Hyundai Rotem and expected to gradually replace the obsolete Leopard and M-60 tanks. Barring unforeseen technological hurdles, the Otokar company will put the battle tank in service before the end of 2021.

Founded in 1984, TAI specializes in earth observation and surveillance satellites and manufacturing components for the Airbus A350 and Airbus A400M programs. TAI and SSB are involved in a large project to manufacture the TF-X, a fifth-generation fighter that will replace the F-16. The program has gained greater importance for Turkey after the U.S. decided to halt F-35 jet deliveries.

Erdogan’s controversial decision to purchase the S-400 surface-to-air missiles angered the U.S. and drove the Trump administration to punish Turkey for turning to Russia for military procurement. The U.S. successfully pressured BAE Systems and Rolls-Royce to withdraw from partnerships with Turkey to build the engines for the TF-X.

Turkey opted instead to manufacture its engine and subcontracted Aselsan and TR Motor to develop an indigenous engine. The United States’ punitive measures will delay the launch of the TF-X maiden flight from 2023 to 2029. Turkish officials tried to market the TF-X project as the first Islamic jet, but their attempts to make the TF-X jet a multi-partied program did not succeed. Ankara invited Malaysia to become a partner, and Kuala Lumpur did not respond. Perceiving the project as a black hole, Pakistan, Indonesia and Kazakhstan chose to stay out of it.

The Turkish defense industry faces serious challenges that include brain drain, currency devaluation, uncertain foreign supplies and regional disputes. The financial crisis in Turkey caused purchasing power for the majority of citizens to plummet. Talented Turkish scientists left the country to pursue lucrative employment offers commensurate with their qualifications. Turkey’s poor relations with most countries in the Middle East dampened the outlook for its arms exports.

Moreover, the defense industry is inherently fragile because it relies heavily on foreign inputs, many of which come from Europe. In the last quarter of 2019, the European Union placed restrictions on the export of raw material and components used in Turkish arms. Frequent sanctions and embargoes hamper its arms production and deny it access to advanced military technology. Its military products are mostly conventional, outdated and poorly made.

Projecting Power

In criticizing the U.S. for excluding Turkey from the F-35 program, Erdogan said Washington awakened a sleeping giant determined to achieve self-sufficiency in fulfilling its military equipment needs.

He boasted that Turkey is involved in executing some 700 arms projects. In December 2018, Erdogan signed a decree to privatize the famous Tank and Pallet Factory to be run by a joint Turkish-Qatari firm for 25 years. Many Turkish nationalists have become convinced that involving a foreign country in its operations undermined Turkey's national security interests.

Erdogan sees beyond national security in the narrow sense and aspires to establish a greater role for Turkey in regional affairs.

Erdogan believes that a deterrent military capability is essential for achieving regional power status.

Already there is evidence to suggest it has. Turkish military support for the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord recently turned the battle against the forces led by Khalifa Haftar, backed by the UAE, Russia and Egypt. A few months ago, Turkish UAVs inflicted heavy casualties on Syrian regime forces and halted their advance on Idlib.

Erdogan does not trust the weapons suppliers in the West and has a political vision that distances him from NATO. He is bitter because eight NATO member states sent troops to Lithuania to deter Russia from intruding into the Baltic states, but none of them expressed interest in sending troops to northern Syria to protect the southern flank of the alliance.

In that sense, Erdogan’s defense industry is part of his larger regional ambitions. He sees himself as a reformer and architect of regional power. To that end, he has reined in the Turkish military, which had previously been seen as the guarantor of secularism and republicanism, and he has dismissed from service all the participants in the 2016 coup attempt, including their supporters in the bureaucracy and academia, jailing about a third of the top brass in the army and air force.

Erdogan’s policies have drawn comparisons to Mahmud II, who became Ottoman sultan in 1808 and endeavored to modernize the ailing empire. The problem is that he is remembered for massacring thousands of Janissary soldiers for dominating the public sphere and corrupting the state machinery.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario