by: Jim Sloan

Summary

- The 1918 economy was so different from 2020 that important economists see no profit in comparison, but it has one important common factor: the impact of a sudden event.

- Traditional economists saw the mild 1918-19 recession and the deep 2020-21 depression as separate events; modern revisionists make the case that they are parts of one event lasting five years.

- Revisionists have advanced a new model of a "sudden shock" which produces powerful lingering effects akin to those of the Reinhart-Rogoff model; three 1980-2008 crises in Mexico serve as examples.

- The Fed must take care in fighting the crisis not to undercut the principles of price discovery and creative destruction; prudent investors should follow elder statesmen in not taking precipitous actions.

- The impact of the 1918 pandemic on individuals is captured in the book cited below - a small masterpiece written 60 years later which may suggest the lingering emotional scars.

- Traditional economists saw the mild 1918-19 recession and the deep 2020-21 depression as separate events; modern revisionists make the case that they are parts of one event lasting five years.

- Revisionists have advanced a new model of a "sudden shock" which produces powerful lingering effects akin to those of the Reinhart-Rogoff model; three 1980-2008 crises in Mexico serve as examples.

- The Fed must take care in fighting the crisis not to undercut the principles of price discovery and creative destruction; prudent investors should follow elder statesmen in not taking precipitous actions.

- The impact of the 1918 pandemic on individuals is captured in the book cited below - a small masterpiece written 60 years later which may suggest the lingering emotional scars.

"It happened too suddenly, with no warning, and we none of us could believe it or bear it ... the beautiful, imaginative, protected world of my childhood swept away."

- So Long, See You Tomorrow,

William Maxwell´

The 1918-1919 "Spanish" Flu pandemic is the closest event in U.S. history to the current coronavirus pandemic notwithstanding a number of major specific differences. The American economy was very different then. The Dow Jones Industrials - then 20 stocks - contained sixteen companies involved in either commodities or basic manufacturing, plus AT&T, Western Union, and Studebaker (Ford being a privately owned company).

In 1918 a third of the American working population were farmers (versus 1 or 2% today). Farmers could not observe anything like a lock down. Another 28% of the economy was manufacturing (versus 8% today). The Amazon (AMZN) of the day was Sears with its catalogues.

Instead of dollar stores there were dime stores. The country was 50% urban and 50% rural versus 83% urban today. The service economy, now the largest sector, consisted mainly of small local businesses. Aside from the ongoing war in Europe, government made up just 1% of the economy.

A key takeaway is that most of the 1918 economy served relatively simple and immediate human needs, and much of it was local. Shut downs were primarily done by cities, with just a few states getting involved. The length of the average shut down was about a month, and the directed full or partial closures included churches, theaters, barber shops, and saloons.

There was little in the way of national media, and newspapers were the major source of information outside one's immediate neighborhood. Information about the outside world came slowly to much of the population. There was nothing like CNN or Fox News telling their followers how to frame their thinking. The New York Times still served as an objective national newspaper of record.

When the pandemic began American troops were arriving in Europe at the rate of 10,000 a day and rushing to the front where their presence helped to halt the last desperate German offensive. As the second wave of the pandemic began in late summer American troops were making their weight felt in the counterattack which eventually forced the unexpectedly quick German surrender. American lives lost in the war amounted to 116,000, of which around 40% were from battle wounds and 60% from illness, many from the Spanish Flu.

The above were the major facts of life in 1918 and the important events of the world as experienced at the time. We all know how the world looks today. That is, we each have our own model of it depending on our allegiance to Fox or CNN, or to our abilities to stand back and look for reliable facts then frame our own individual opinions.

One seldom mentioned but important economic fact about 1918 was that the war ended suddenly.

Most people at the time believed it might go on for years - it had already gone on for four years of stalemate on the Western Front - but starting in September the German army suddenly and unexpectedly collapsed. In Germany this led to the folk myth of betrayal by the leadership at home - and ultimately to Hitler.

In the U.S. it left an extraordinary inventory of raw materials along with a mix of wartime price controls which suddenly needed to be unwound. It also meant the return of several million soldiers, many of whom had no jobs to return to. This single fact of the war's sudden end may be a possible bridge between the views of economists who believe the 1918-19 recession was mild, insignificant and quickly over and revisionists who believe its impact extended as far into the future as 1923.

That argument has major importance today as we attempt to frame a model for the sudden and intentionally engineered economic shut down of 2020.

Two Schools Of Thought On The 1918 Event

The years from 1917 to 1923 are among the least vivid in the memory of most Americans, historians included. This is strange considering the number of important events which took place over that period. Considering its importance, very little serious research has been done about the economic impact of the 1918 pandemic - until a recent outburst, that is.

Most economists have been satisfied to accept the view that the pandemic probably triggered a minor and very brief recession which one has to look closely to identify on most charts. Among the factors discouraging serious research was the fact that in 1919 national high-frequency economic data was rudimentary. National Income Accounting as we know it today was not invented until 1932 (by Simon Kuznets), and naturally turned its immediate attention to the 1920s and 1930s.

With the arrival of the 2020 pandemic there has been a recent surge in papers about 1918 and its aftermath, although no less a figure than Carmen Reinhart (coauthor with Kenneth Rogoff of the authoritative This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly) recently stated that the times were so different that 1918 is not helpful in thinking about 2020. Other economists beg to differ.

Two distinct schools of thought have emerged, and their major point of contention has been the proper period to examine. Is it the simple duration of the pandemic, the course of which was mainly between spring of 1918 and spring of 1919?

Or does the period include the "Forgotten Depression" of 1920-21 and its aftermath?

The answer to that question has very major significance for those trying to model the future of the present economy.

The first view to come to my attention was Chicago Fed Working Paper No. 2020-11, "What Happened to the US Economy During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic? A View Through High-Frequency Data," by Francois Velde.

Velde's focus is on the economy over the brief period of the pandemic itself (mainly spring 1918 through spring 1919). His paper provides detailed data, including some that I used in the introductory passages, as well as anecdotal reports from newspapers. Much of his data was pulled together laboriously by assembling the available data from cities and states.

Here is Velde's abstract:

Burns and Mitchell (1946, 109) found a recession of “exceptional brevity and moderate amplitude.” I confirm their judgment by examining a variety of high-frequency data. Industrial output fell sharply but rebounded within months. Retail seemed little affected and there is no evidence of increased business failures or stressed financial system.

Cross-sectional data from the coal industry documents the short-lived impact of the epidemic on labor supply. The Armistice possibly prolonged the 1918 recession, short as it was, by injecting momentary uncertainty. Interventions to hinder the contagion were brief (typically a month) and there is some evidence that interventions made a difference for economic outcomes.

Velde sees a distinct separation between events in 1918-19 and events in 1920-21, largely because the minor dips in various economic trends appeared to recover fully within that period.

The stock market, as he shows, dropped 33% in 1917, recovered and significantly exceeded the point from which it dropped, then dropped 47% in 18 months from the beginning of 1920 to July 1921. At the bottom of the second drop the market reached a PE ratio of less than 6, one of the lowest DJI PEs ever recorded.

The fact that the two bear markets took place within such a short period doesn't appear to disturb Velde. This point of view is not hard to understand because the second bear market is so readily explained as the result of well-understood factors. In 1919 there was a common form of post-war inflation in which consumer demand ran ahead of production and prices jumped roughly 14%.

This alarmed the Federal reserve, which was still in its infancy and had not yet been tested by a serious crisis. The Fed tightened money quickly and radically, driving rates from 4.75% to 7% by June of 1920, the sharpest increase in history aside from the Volcker actions which ended the inflationary 1970s.

Meanwhile the demobilization of the armed forces from 3 million in 1918 to 380 thousand in 1920 created massive unemployment and a deep and highly deflationary Depression. What happened next - surprisingly - was... nothing. As James Grant was delighted to point out in his book The Forgotten Depression: 1921: The Crash That Cured Itself, the invisible hand of laissez faire inaction took over.

The economy righted itself, the former soldiers found jobs, and the Roaring Twenties were off and running. This way of looking at the 1920-21 downturn defined it as an entirely separate event deriving from the crosscurrents and dislocations presented by the war.

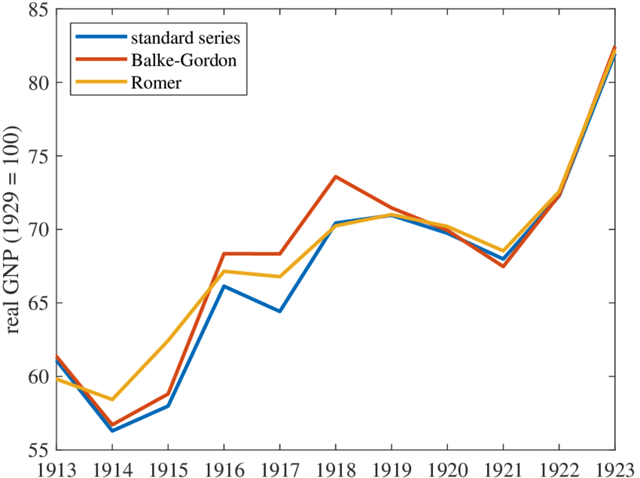

Among the Velde charts, however, was the following depiction of annual real GNP including both the standard series and revisionist models by Romer (1988) and Balke-Gordon (1989). Although not noted by Velde, the Balke-Gordon series (represented by the red line) suggests to me that the decline in real GNP actually began in 1918 and continued into 1921. This presents the outline of an argument that the two economic declines were in fact sequential elements of the same event.

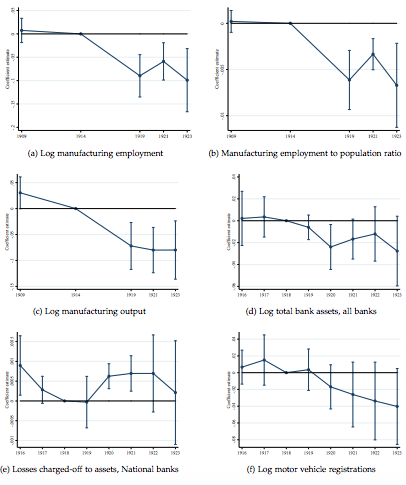

The revisionist Balke-Gordon view was greatly expanded upon by Sergio Correia, Stephen Luck, and Emil Verner in their recent paper "Pandemics Depress the Economy, Public Health Interventions Do Not: Evidence from the 1918 Flu" (March 30, 2020).

Correia et al are at pains to demonstrate that NPIs (Non Pharmaceutical Interventions such as lock downs) are positive for both health and the economy, but their more interesting argument, as demonstrated in the graphs below, is that the lingering effects of the 1918 event continued through 1923. This is an argument of utmost importance and some concern with respect to the current coronavirus event.

Correia et al therefore stand in stark contrast with the view of Velde and previous economists writing long before the present virus who argued that the damage from both the virus and NPIs was limited to the period of the virus itself.

This is not good news for those who are beginning to treat the appearance of a vaccine or effective treatment as marking the end of damage from the virus. Velde, however, had seen the Correia et al paper prior to publication of his paper and addressed it in the final line of his own work:

My conclusion contrasts with the recent evidence on long-run outcomes (Correia, Luck, and Verner 2020). The challenge in reconciling the two sets of findings is to identify a state variable through which the disturbance of 1918 could have propagated all the way to 1923.

That is the crux of the matter. Defining the variable connecting the second event (1920-21) to the first (1918-19) would completely change the thinking about economic effects following the 1918 pandemic. Another paper may provide the answer.

The "Sudden Stop" Model Typified By Mexico

A paper written in 2017 ("On the Legacy of Financial Crises: Lessons from Mexico’s Sudden Stop History," Gianluca Benigno, Andrew Forster, Christopher Otrok, Alessandro Rebucci, 19 April 2020) may provide a new way for defining and comparing exceptional events such as 1918 and 2020.

The basic premise of Benigno et al is that economic crises resulting from a "sudden stop" are altogether different from crises which unfold "normally" over time because of underlying economic trends. To illustrate the impact and duration of "sudden stop" crises the authors focused on Mexico.

Mexico has been especially prone to "sudden stop" crises because of its dependency upon debt denominated in other currencies, mainly the dollar. I personally remember the first of the three crises in the charts below because a friend of mine noticed the arrival of a bank examiner he knew entering the Continental bank and called to let me know, resulting in the best 24 hour short in my career.

The second, called the "tequila crisis" resulted in part from the assassination of a presidential candidate followed by a peso collapse which brought the Clinton cabinet to the edge of a nervous breakdown. The third was Mexico's participation in the global crisis of 2008, which fell more heavily on Mexico because of its lack of ready access to capital.

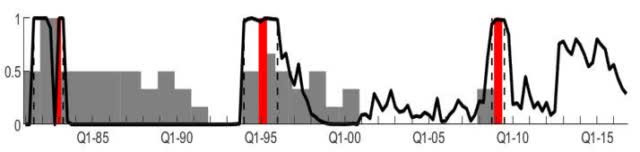

Comparing the three events in the chart below, Benigno et al described a general model of what happens when an economy suffers a "sudden shock" from an unanticipated event. Images come to mind: a passenger without seatbelt going through the windshield when a speeding car hits a telephone pole or a rider taking an "arser," as the British say, when a galloping horse balks a barrier. You get the idea.

Figure 1 Mexico's model-identified crisis episodes

Notes: The black line is the estimated model-implied probability of being in a crisis. The grey bars correspond to the tally index. The red bars indicate model-identified crisis peaks. The vertical dash lines mark the beginning and the end of the estimated crisis episodes.

This paragraph from Benigno et al provides their description of the aftermath.

The economy rebounds quickly from these episodes, but only partially, making up only half of the ground lost during the crisis episode, or about four percentage points in these simulations. After the initial bounce, a combination of persistently adverse circumstances produces a protracted output decline, as we can see in the Mexican data after the debt crisis ...and also in line with empirical evidence on the long-term consequences of financial crises in other emerging and advanced economies (Reinhart and Rogoff 2009).

The international cost of borrowing remains elevated for an extended period, even though spreads revert after the crisis. The productivity decline is sizable and very long-lasting, with technology reaching a level that is below the one at the beginning of the boom. During the post-crisis period, investment and to a lesser extent consumption also stagnate below their pre-crisis levels. As a result, credit flows remain above (below) their pre-crisis level long after the crisis has ended, although the economy is no longer financially constrained."

In other words, the contamination caused by a "sudden stop" has a more or less predictable half-life extending meaningfully for at least five years.

There is no question that the current economic situation can be described as a "sudden stop" - perhaps the most abrupt and severe sudden stop in history. You have to be an economy as sophisticated as ours with a capital intensive service sector like our airlines, cruise lines, casinos, restaurants, and hospitality to hit the wall with such an enormous thud. The way we live now and Fed policies encouraging the use of debt set us up for this.

The 1918 event was also a "sudden stop" of sorts, but to think of it in those terms it is necessary to fuse the end of World War I and the pandemic into a single event, which in terms of time and commingled effect they certainly were.

The "sudden" part of it is more attributable to the War than to the pandemic, as no one at the time anticipated anything like it - no one except the German generals who experienced the sudden defeats starting in September 1918. Although they still occupied Allied territory, Hindenburg and Ludendorff visualized an endless pipeline of war materials and fresh American divisions and informed the Kaiser, who then abdicated. After four years of stalemate the war came to a sudden stop.

What followed was a series of wild swings between inflation and deflation, scarcity and abundance, and triumph accompanied by tragedy. The remarkable thing was that the declines in the economy remained relatively shallow despite lasting until 1923. The main reason was the incredibly robust growth in the American economy at that time driven by a number of new technologies.

The "persistently adverse circumstances" which Benigno et al did not attempt to describe in detail had mainly to do with what economists call "imbalances," wild swings between too much supply and too much demand plus a suddenly expanded labor force. It took five years for the wild oscillations to diminish.

The present shock to the economy is probably closer to the Mexican crises in its suddenness, absoluteness, and depth. The stock market rally may resemble the huge bull market of 1919, in which the Dow Industrials nearly doubled as the financial world felt the worst was past, only to fall by 47% in 1920-21. The state of the economy going into the present crisis appeared reasonably good but its fragility was displayed immediately by the number of companies and households for which debt problems were severe and immediate.

If these broad descriptions are right, the Federal Reserve has years of heavy lifting to do. The basic "sudden shock" model suggests that recovery as the economy reopens will at first go swiftly but stall out when it has recovered about half the ground to its level at the onset of the crisis. To get all the way back will take a minimum of five years. Jay Powell has hinted at that. In a recent interview shared with Reinhart, Ken Rogoff opined that five years was the best case we could hope for.

It's not my intention to frighten anyone, and things may conceivably go better than that, but the "sudden shock" estimate of 50% recovery, a stall, and at least five years to get back to par seems to me the reasonable starting model for the economic future. Like all such models it should be updated regularly in response to actions or reported results different from those predicted. This isn't far from my 60% probability model in this earlier piece from May 4. Since then both the Fed and the Congressional leadership have done reasonably well, so the model in this article may be ever so slightly more positive in tone.

What Are The Investment Implications

Readers are probably tired of articles with no very clear investment implications, and I regret having to write them, but I suspect all of us would do better to be worried about articles that pick around the edges of the markets with specific buy recommendations in an economy where the macro uncertainty is so great that it overwhelms all other arguments.

The true answer is that we just don't know. People like Howard Marks, David Tepper, and Stephen Druckenmiller - and Buffett of course - who have repeatedly said to trim your sails and and sit tight are doing you a service.

One thing we have to note is that the Fed has to thread a needle here. It has to put out fires that would pull the system under but avoid in doing so the even worse outcome of destroying fundamental tenets of the capitalist system. Price discovery in stocks, bonds, and commodities is essential to the workings of the system, and sooner or later we have to step back, grit our teeth, and let it happen.

Creative destruction, the Schumpeter term, is also an essential part of the system. Capitalism requires periodic failures which clear the way for new growth like forest fires. The Fed must take care that their stop-gap rescues in areas like corporate bonds don't spare companies which should by all rights go under.

Two of the areas I'm watching closely are banks and insurance companies. Banks were in great shape going into the crisis, and I own JP Morgan (JPM), Bank of America (BAC), and U.S. Bank (USB). All of them would have done very well with even with a high level of defaults - maybe a couple of years of flat to down earnings at worst. The Fed, however, has imposed duties on them which stretch their capacity and in the process has incurred a moral obligation to make good any problems that arise for the banks from this service.

Insurance companies should have been one of the few safe areas of the market, slow growing but more or less immune from risks that they are expert at assessing. Several states, however, have moved to hold them accountable for business risks due to the pandemic which are not in their property and casualty contracts. These actions will probably not survive the courts, but it's impossible to be sure.

Litigation cost was probably one of the things on Buffett's mind in his cautionary views at the recent virtual annual meeting. I'm keeping my large position in Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A)(BRK.B) but sold positions in both Chubb (CB) and Traveler's (TRV) which had seemed to be, and should have been, rare safe havens. If insurance companies are required to make good business losses they didn't contract for, who will make good the losses absorbed by the insurance companies?

What will happen to business in general if the specific language of contracts ceases to be enforced? The rule of law is one of the underlying principles in ranking a country's suitability for investment.

What Are The Human Implications of The Pandemic

You may have noted that I said nothing about the importance of a vaccine, antibodies, or treatments of any sort. I will be happy when we have one or all of these and especially pleased to find myself still alive and healthy and able to make use of the medical miracles. I do not think, however, that getting vaccines or palliatives is the secret to saving the economy. A second and more deadly wave of the virus could probably make things worse, but it's already too late for a cure to change the basic outcome. The economic problems discussed above are more or less baked into the cake. Cures are for you and me and our children, grandchildren, and great grandchildren and will enable us to rebuild.

And we will.

The immediate human impact, however, matters. Despite the many debates on the lock down, we have chosen this time to put human lives above the economy. Headlines today note that we will soon pass 100,000 deaths. What the headlines do not say is that at the 1918 rate of infection and mortality, and noting that the US population has more than tripled, we might have ended up with more than 2.5 million. It could, in other words, have been much worse.

Writing in 2007, Thomas Garrett of the St. Louis Fed dealt fully with the impact of the 1918 pandemic and efforts to reduce its impact, but included this surprising paragraph:

The influenza of 1918 was short-lived and “had a permanent influence not on the collectivities but on the atoms of human society – individuals.” Society as a whole recovered from the 1918 influenza quickly, but individuals who were affected by the influenza had their lives changed forever."

One of those "atoms" was William Maxwell who lost his mother to the pandemic at the age of 8. Maxwell grew up to be a legendary New Yorker editor and produced the short novel quoted at the top of this article.

Maxwell's novel is a small, perfect masterpiece and has become the classic creative work to come out of the 1918 pandemic which it captures in the way that classic novels like All Quiet On The Western Front captured the essence of the war.

An autobiographical novel written 60 years after the experience, So Long, See You Tomorrow (1980) is about absence and loss as experienced by a child and remembered with adult insight.

It has a plot based upon the narrators's betrayal of a friend and an actual murder case in small town Illinois. The book was suggested to me thirty years ago by a friend, recommended for its direct and unpretentious prose, and I found myself becoming part of a literary cult who believe Maxwell, who died in 1992, was one of our great writers.

If you see the current pandemic in terms of individual human beings and are a person who experiences events through exquisitely crafted literature, you might spend the two or three hours it takes to read it.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario