The army vented its frustration this week over its losing competition against the IRGC.

By: Caroline D. Rose

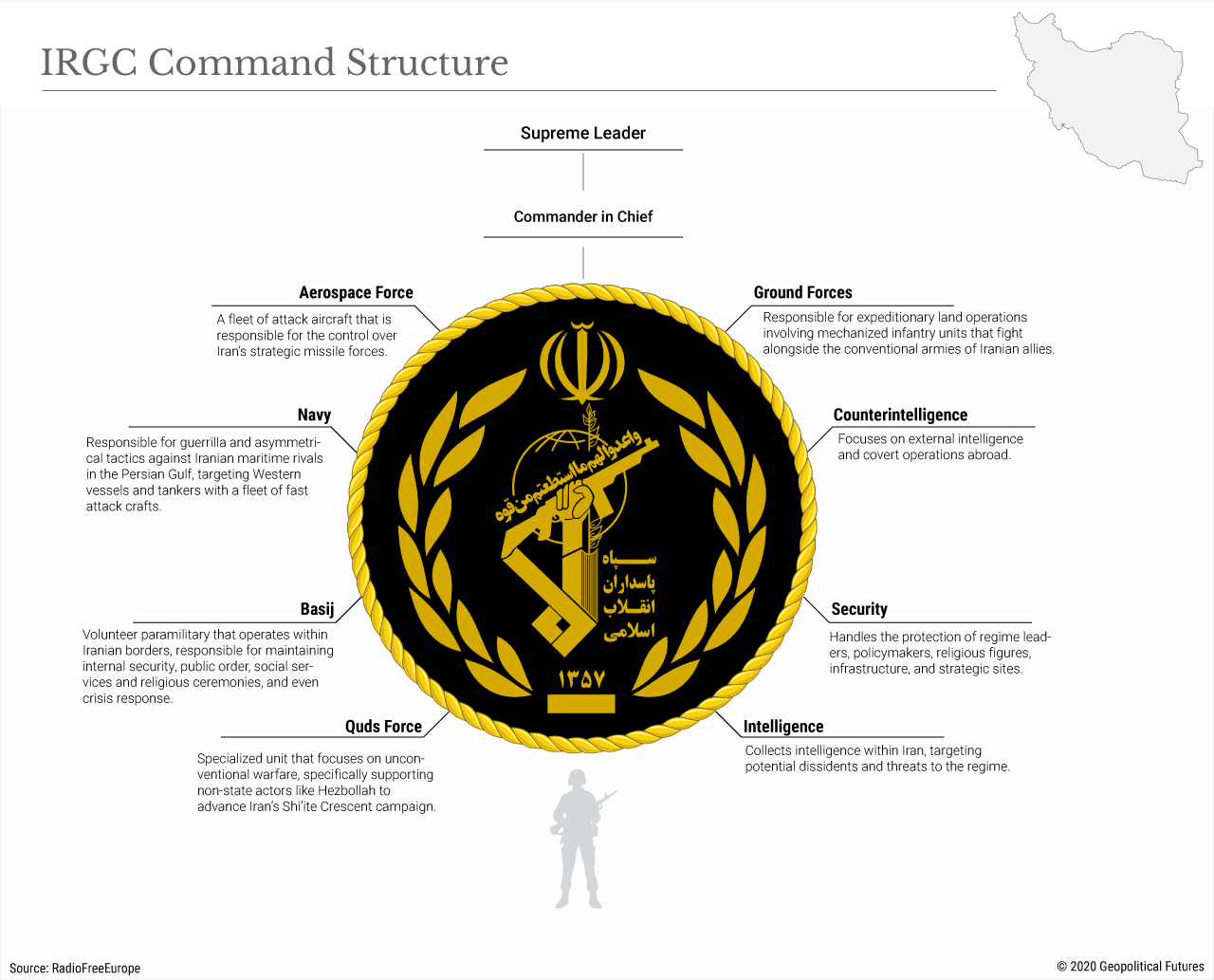

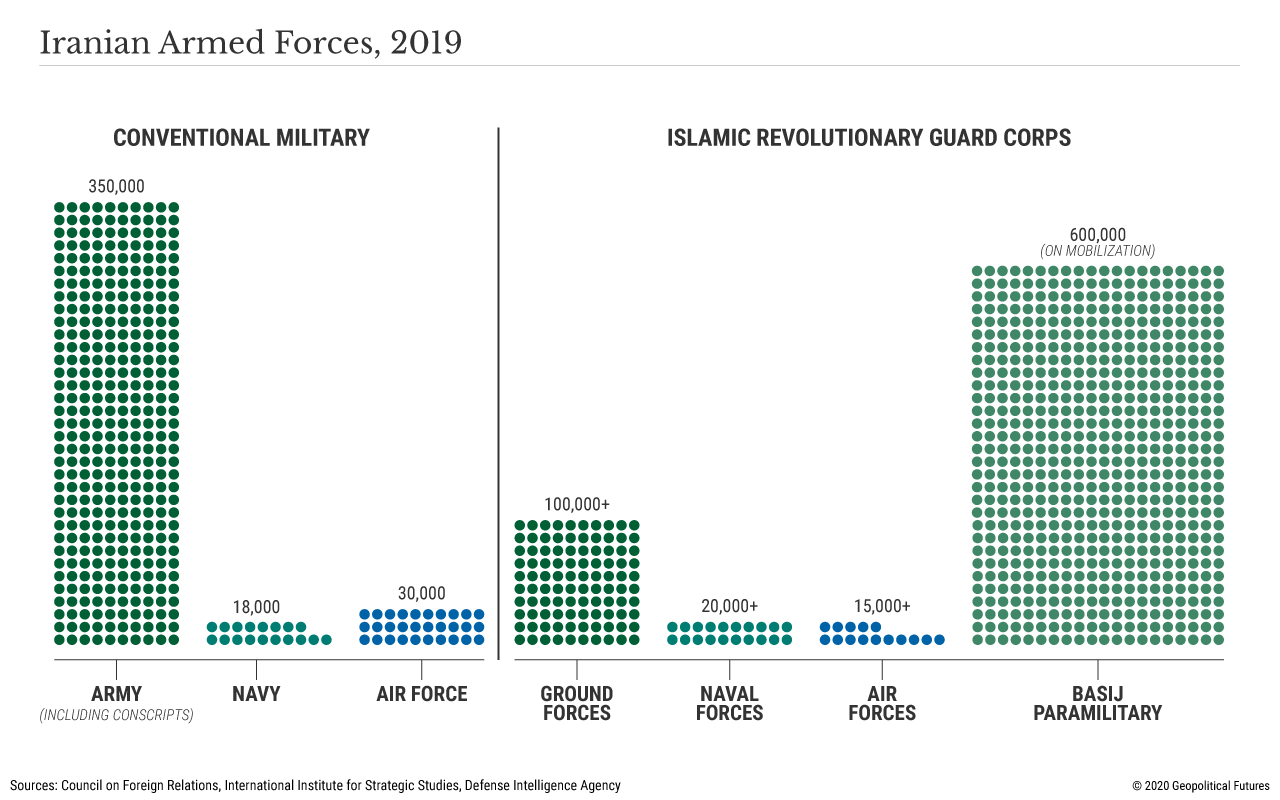

| The interview was deleted within hours of publication, likely at the direction of the government, but for a moment, the world got a glimpse into Iran’s deep-rooted inter-service rivalry. The competition between the conventional army, known as the Artesh, and the IRGC has been a central feature of Iran’s military landscape since the 1979 revolution. But unlike a lighthearted army-navy game or bureaucratic tussles over funding, this is a perilous fight over economic, political and ideological influence in which only one side can win. It is a battle over not only operational capabilities, but the direction of the country. Since the 1980s, the IRGC – considered the guardian of Shiite Islamism, whereas the Artesh has always had a secular-nationalist bent – has had the upper hand. The IRGC’s growing portfolio of responsibilities, its control over the formal and informal economies, and the favor of the political establishment have enabled it to transcend and upstage the Artesh. Facing a global recession, the coronavirus pandemic and continued U.S. sanctions, the Iranian government will have to make budget cuts. Awareness of that fact has pushed the Artesh to intensify its fight to win funding and impose its ideological agenda. But financial constraints and festering socio-political discontent against the government will ultimately stack the cards in the IRGC’s favor, enabling it eventually to absorb the duties and resources of Iran’s waning conventional army. History of Bitter Rivalry Cracks in the foundation of Iran’s armed forces have been evident since the Islamic Republic came into being in 1979. When Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini dethroned the shah, he faced a decision: dismantle the shah’s Imperial Guard completely, or reform it to fit within the revolution’s set of principles. Despite political and clerical pressure, Khomeini chose the latter option, wishing to retain the force’s expertise. The shah’s army was heavily purged, indoctrinated and renamed the Islamic Republic of Iran Army, commonly referred to as the Artesh. Even with these changes, the government remained uncomfortable with the Artesh’s affiliation with the toppled regime, suspicious of potential loyalties to the shah and secular nationalism. Those suspicions were confirmed after the Nojeh coup plot, an attempt to overthrow the Islamic Republic in 1980, was found to have involved Artesh servicemen. Out of concern for his own safety, Khomeini was forced to put more trust in the militias that fought on the side of the revolution before becoming the IRGC. The IRGC and the Artesh were enshrined in Iran’s 1979 constitution as parallel forces, but ambiguous wording enabled Supreme Leader Khomeini to empower the former and keep the latter on a tight leash. For example, Article 143 says the Artesh is responsible for guarding the “independence and territorial integrity” of Iran, while the IRGC defends “the revolution and its achievements.” Those revolutionary “achievements” have come to carry greater meaning in post-revolutionary Iran, encompassing not only internal order but also control of a network of Shiite proxies across the Levant. While the Artesh protects Iranian territory in the event of a ground attack, the IRGC has emerged as a flexible tool for the advancement of the government’s domestic, intelligence and foreign priorities. Because of this, the IRGC has been able to establish ground, naval, aerial, domestic security, disaster relief and even aerospace branches, which were initially presumed to be under the Artesh’s purview. The Artesh’s navy, air force and army all conduct routine annual maritime and ground patrols and exercises and project Iranian conventional military power. But as Iran is not a conventional power – it lacks modernized weaponry, strategic mobility, balanced defensive and offensive capabilities, and the ability to conduct cross-spectrum operations – the Artesh is largely obsolete, and it’s left to the IRGC to perform the heavy lifting of defending the country. IRGC vessels have been the primary agents harassing U.S. 6th Fleet warships, assaulting foreign oil tankers and disrupting shipping through the Strait of Hormuz. The IRGC’s domestic paramilitary, the Basij, has been responsible for internal security (quelling protests and internal dissent) and natural disasters, and has even served as the key COVID-19 response team. And as the heart of Iran’s core foreign policy mission, the “Shiite Crescent,” IRGC ground and air forces have been instrumental in sponsoring pro-Iran militias and strikes on Western troops in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and the Palestinian territories, all in an effort to pave an avenue of influence into the Mediterranean. Not only has the IRGC’s mission ballooned over time, but its budget has as well. The Artesh’s budget, meanwhile, has been incrementally downsized, even though it employs more personnel and is considered Iran’s conventional force. IRGC command has gained sway over the Iranian parliament, advisory bodies and the economy. IRGC members outnumber Artesh representatives among Iran’s political elite, with more advisers at the side of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and in the national parliament, the Majlis. The IRGC even exercises some institutional control over the army itself: The Revolutionary Guards holds the reins of the Armed Forces General Headquarters, which acts as an intermediary between the supreme leader and Artesh command. As a result, the IRGC is the first to review Artesh planning, resources, logistics and operations. And, importantly, the IRGC enjoys more independence from the state budget, with exclusive access to Iran’s foreign exchange reserve, ownership of roughly one-fifth of the market value of the Tehran Stock Exchange, a hand in the black market, and access to many of Iran’s oil and gas sector contracts. The IRGC’s financial semi-independence has proved helpful, as sanctions and a painful economic recession have quickly chipped away at Iran’s defense spending. A Losing Battle The clear disparity of power between Iran’s parallel services has bred resentment among the Artesh’s command about the service’s atrophying budget and influence. For decades, the Artesh has made a tradition of keeping its mouth shut, praising Islamist principles and Khamenei’s leadership, and taking a backseat to the IRGC. Yet new opportunities for funding, such as the potential lifting of the U.N. arms embargo in October (the five-year embargo expires on Oct. 18 under the terms of the Iran nuclear deal, but it could be extended), as well as budget considerations due to sanctions have incentivized the Artesh to speak up. The potential strength of the Artesh comes not from within but from the tacit threat that it could galvanize nationalist sentiment among regime opponents. The Artesh believes it can pressure the government by appealing to secular-nationalist factions in the Iranian population, many of which rallied against the government at the end of last year. But this is a risky gamble for an already diminished force to make. Despite its efforts, the Artesh has not convinced the government of its worth. Limited by aging armaments (many are holdovers from the shah’s time), unserviceable machinery and a budget now less than half the IRGC’s, the Artesh has tried to keep its head above water. But the fact that the Artesh has become second class to the IRGC has led to substandard performance among its demoralized personnel. Lower pay, fewer benefits and a lack of career mobility have affected the Artesh’s recruiting, enabling the IRGC to pick from among the most talented recruits. This has led to a string of mishaps among the Artesh’s branches, the most recent example being the May 11 friendly fire incident between two Artesh navy vessels, the support ship Konarak and the frigate Jamaran, which killed 19 and injured 15 of its own personnel. The Artesh’s recent mistakes and pressure tactics won’t work to change minds within a government overwhelmingly favorable toward the Revolutionary Guards – especially after the election in February increased the number of pro-IRGC conservative hard-liners in the Majlis. In fact, the Artesh’s waning relevance and tight budget, combined with growing socio-economic grievances among the public, will only push Tehran closer toward allowing the IRGC to absorb the Artesh’s functions and resources. Drawing from some of the Artesh’s resources, the IRGC’s funding for its Levantine operations and efforts to quell dissent at home will receive a boost. Nevertheless, increasing U.S. sanctions, an internal economic crisis and rising opposition to Iranian influence in the region will continue to constrain Iran. | |

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario