By: Ridvan Bari Urcosta

Most countries naturally tend to rely on their strengths to increase power and influence abroad.

For China, this means using its substantial economic resources and propaganda (i.e. manipulation of its public image) to coerce foreign countries into partnering with Beijing and the broader international community into believing it can compete on a global scale. Its efforts to boost its influence abroad have, of course, been concentrated on Southeast and South Asia, but more attention has been paid to China’s push into Europe, particularly Eastern Europe.

The region has turned into a symbolic battlefield for the United States, Russia and now China as they each compete for power and prestige in the region.

China even dubbed 2020 the “Year of Europe,” signaling a desire to improve ties across this strategically important market. When Beijing launched the campaign, the U.S. and EU were in the early stages of what looked to be an emerging trade war, and China saw an opportunity to take advantage of the situation.

Much has happened since the beginning of 2020, most notably a global pandemic, but even before the coronavirus, China’s ability to increase its influence in Europe was always questionable because it would have to rely so heavily on propaganda and manipulation as it championed its achievements in building diplomatic bridges, constructing key supply networks and infrastructure, and providing much-needed credit for cash-starved countries that didn’t want to rely on Western institutions.

But in reality, China’s engagement with Eastern Europe is not nearly as strong as the headlines suggest, and its weaknesses will only be exacerbated by the pandemic. For both sides, the goals of engagement have little to do with strengthening relations between them. Rather, Beijing is using its relationship with countries in the region to expand its leverage against the U.S. and the European Union.

Likewise, Eastern European countries are using China to increase their negotiating power over Washington and Brussels, both of which are wary of China’s increasing presence across Eurasia. Ultimately, they see each other as a source of leverage in their relationships with other critical players rather than strategic partners in their economic and security agendas.

At the center of China’s outreach to Eastern Europe is its Belt and Road Initiative, an ambitious plan to revamp the supply chain across Eurasia using loans, often with unfavorable terms to the borrowers, to build infrastructure that will connect the entire Eurasian landmass via roads, rail and ports. The project will allow China to sell its exports, a critical part of its economy, to markets abroad using a supply chain that Beijing itself helped build and largely controls.

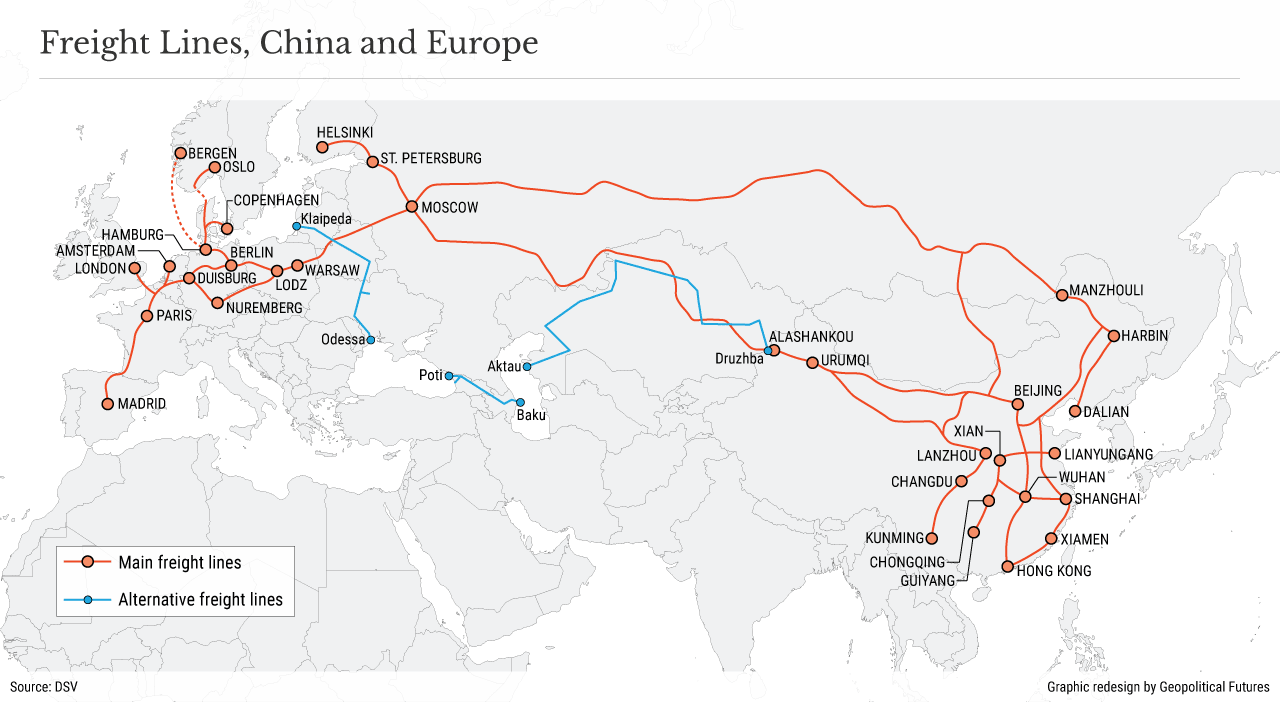

In the 2010s, China’s expansion into Eastern Europe has been focused in large part on rail. The so-called China-Europe Express, a series of railway routes connecting China to European markets, requires the participation of countries in Eastern Europe, the gateway to other valuable markets in the European Union, most notably Germany.

But the rail project isn’t as big of an achievement as it’s been touted to be, mostly by Beijing itself.

All the railway routes in the China-Europe Express have actually existed since the Soviet era.

The project, then, is really about repurposing and upgrading existing infrastructure rather than building an entire network from scratch – which would be a much more ambitious and complicated project.

Constructing an entirely new rail route to Europe would require getting the approval of many countries through which this network would pass, a politically challenging endeavor particularly given that China prefers to conduct negotiations on a bilateral basis.

While some countries may be open to accepting China’s help to improve their own infrastructure, they may not be willing to participate in Beijing’s broader vision for Eurasia. In addition, this project has run into technical complications, including the lack of standardization of rail gauges among the different railways, which slows down the transit of goods. Financing is also an issue.

Upgrading this rail system would require massive investments, and China simply does not have the capital to complete such a project. Even before the pandemic, its economy was struggling with problems that were only aggravated by the U.S.-China trade war. In fact, Beijing’s investments in Europe fell to 11.7 billion euros ($12.6 billion) last year, just a third of the total at its peak in 2016.

China has made many grand announcements about BRI’s achievements in Europe, but in reality, some of its most high-profile projects in the most geopolitically significant Eastern European countries have not been executed as Beijing promised. In Romania, for example, the government scrapped a deal earlier this year with a Chinese energy firm to construct two reactors for the Cernavoda nuclear power plant.

Similarly, plans to have a Chinese company help construct the Tarnita-Lapustesti Hydropower Plant were shelved in 2015. In Hungary, at least seven projects agreed to by China have failed to get off the ground, including a cargo hub at the Budapest airport and a biotechnology project.

Most notably, the Budapest-Belgrade Railway, for which China would provide the bulk of the financing, has yet to take off after seven years of talks. Both the EU and observers within Hungary have criticized the project because it would require Serbia and Hungary to accept massive loans from Beijing that these countries are unlikely to pay back.

In Poland, President Andrzej Duda and Chinese President Xi Jinping signed a strategic partnership deal in 2016, but little has come of it. In fact, relations between the two countries are arguably worse now, after an employee from Chinese telecom company Huawei was arrested in Poland last year for allegedly spying for the Chinese government.

In another example, Czech President Milos Zeman opted not to go to China for the 17+1 summit in April, in part because China had not lived up to commitments regarding investment. When Chinese President Xi Jinping was in Prague in 2016, he promised around half a billion euros of investment into the Czech economy within the next two years.

To date, none of these funds have arrived. The Chinese-Czech relationship has become increasingly tense, especially after the Czech government improved relations with Taiwan in 2019 and voiced support for the establishment of official bilateral diplomatic relations.

China has relied heavily on propaganda to conceal these shortcomings. In 2012, Beijing launched the “16+1” initiative to improve diplomatic engagement with and strengthen pro-China sentiment in Central and Eastern European states in the EU as well as Balkan states.

Greece joined the initiative in 2019, making it the 17+1. This was, of course, accompanied by EU-China summits and a series of high-profile promises and nonbinding memorandums of understanding on future projects.

By hosting such events and making such announcements, China elevated its profile in Eastern European affairs and gave the world the impression that it was succeeding in the region. It was a savvy public relations move, but no substantial advancements have come with it. China’s failure to deliver on promised funds has started to create problems with the EU, as Brussels has criticized China for its attempts to separate Central and Eastern European members from the rest of the bloc.

On Dec. 5, Pew Research published a report on opinions toward China from around the world.

The Central and Eastern Europeans are somewhat divided in their assessments. More Bulgarians (55 percent), Poles (47 percent) and Lithuanians (45 percent) have favorable than unfavorable views of China, and Hungarians (40 percent favorable, and against 37 percent unfavorable) are nearly evenly divided. But a plurality of Slovaks (48 percent unfavorable) and a majority of Czechs (57 percent unfavorable and only 27 percent favorable) have negative views of China.

Despite China’s difficulties in delivering on its promises, Eastern European countries can still benefit from publicly backing the relationship. Flirting with China enables Eastern European states to build up leverage and bargaining power they would not have otherwise. In some respects, it is another factor to help them counterbalance Russian threats. For much of its existence, Eastern Europe has been a pawn in power struggles between Russia and the West.

Central and Eastern Europe has generally focused their strategic energies outward, toward the Baltic, Black and Mediterranean seas – toward the Rimland, in Spykman’s terminology – rather than inward, toward the Heartland. For these countries, opening up new avenues into the Heartland to connect with China threatens to overthrow the traditional Russia-West competition. It immediately creates geopolitical tension because it signifies Chinese expansion in the spheres of influence of both the United States and Russia, in the case of Belarus.

The projects of most value for Eastern Europe to engage in this game are those of a strategic nature. A prime example is the Rail Baltica project, which aims to connect the railways from Western Europe to Finland via Poland and the Baltic states along a new European standard gauge.

In Chinese plans, such a railway has strategic importance in the delivery of Chinese goods to all corners of Europe, but for the United States and NATO it has strategic importance in terms of military mobility and readiness. Even if China’s ability to follow through is in doubt, the discussion is enough that Washington must pay attention.

Eastern Europe relies on the U.S. presence in the region to counter Russian influence, something China cannot offer. If China were to decide to play a geopolitical role, it would immediately make Russia and China regional competitors; but Beijing is not ready for such a role and so is concentrating on advancing economic connectivity. As long as the United States views its ties with Eastern Europe as strategically important, it maintains the upper hand over Eastern Europe in the relationship.

The Eastern European states’ talks with China, no matter how superficial, are done with the goal of reducing the imbalance in the relationship with the United States. The U.S. has identified China as one of its top threats, and Western Europe is also keeping a watchful eye on Beijing. The days when China could expand its influence unchecked are over, even if Beijing’s strategy for engaging with Eastern Europe reflects its commercial needs — and even if its ability to deliver is limited.

For both the EU and the U.S., China poses a threat to national security, with a case in point being 5G. In an assessment report (“Cybersecurity of 5G networks - EU Toolbox of risk mitigating measures) that the European Union issued earlier this year, Brussels called for improvements in the bloc’s foreign direct investment screening mechanism so that states could better detect foreign investments in the 5G value chain that may threaten the security or public order of more than one EU member state.

This has proved a divisive issue, given that some states are not convinced that China is a national security threat. For example, Chinese telecom giant Huawei employs around 2,000 people in Hungary, where it has invested $1.2 billion since 2005 according to company figures, and now Hungary expects $180 million in investments from China for the construction of the second-largest Huawei supply center in the world.

Notably, Poland and Romania, staunch U.S. allies, rejected Chinese involvement in their 5G networks in favor of cooperation with the United States.

During the Cold War, Eastern Europe was the most important region in the geopolitical rivalry between the superpowers. It now seems that in the new international, multipolar world order, Central and Eastern Europe – and Europe as a whole – will play a serious role.

Chinese success irritates both the U.S. and Russia, especially success in the European continent, which is the traditional domain for both. China does not truly challenge U.S. interests there, but for those states, flirting with China does give them more leverage in their interactions with Washington.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario