By: Hilal Khashan

In October 2017, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman launched the New Future project, his vision of what would drive Saudi economic development in the post-oil era.

The project, thereafter dubbed Neom, is a novel idea as far as the Saudis go; it’s a far cry from Prince Mohammed al-Faisal’s idea in 1977 to tow a 100 million-ton iceberg to the desert to solve a water shortage problem.

But whereas the oil boom dashed al-Faisal’s iceberg dreams, the oil bust has convinced Salman that the future of Saudi prosperity lies in other industries, even a futuristic city that is believed to cost $500 billion.

The Case for Neom

The idea behind the city is to concentrate development and thus foster the accumulation of wealth and ensure the sustainability of growth. Each city would comprise an integrated metropolis consisting of economic clusters equipped with modern facilities providing services, logistics and residential quarters.

The Saudis argue that economic cities such as Neom have a competitive edge because they attract capital for intelligent investments, largely because they require advanced digital and technological systems.

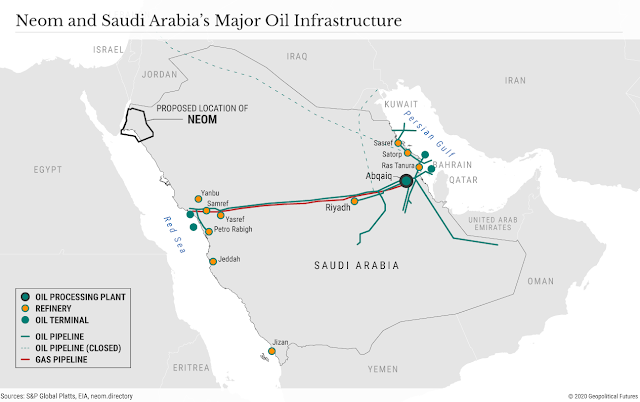

The project, which would cover more than 26,000 square kilometers (10,000 square miles) of waterfront property near Jordan and Egypt, will also focus on renewable energy, water desalination, transport, food production and manufacturing, technical and digital science, advanced industrialization, media production, and recreation.

As part of the framework for Vision 2030, Neom aims to transform Saudi Arabia into a cultural model worth emulating.

The Saudi Public Investment Fund, which owns the project, is marketing it as an ultramodern technological achievement found nowhere else on Earth. Promotional efforts also note that 70 percent of the world’s population would be able to access the city in less than eight hours, thanks to King Salman’s causeway that will connect Neom to Africa and Europe via Sinai. As a unique investment region, the project is exempt from Saudi laws and regulations, such as taxes, customs, and labor laws, and so is designed to attract more foreign direct investment. The execution of the first phase of the project is slated for 2025, and it will take 30-50 years to complete.

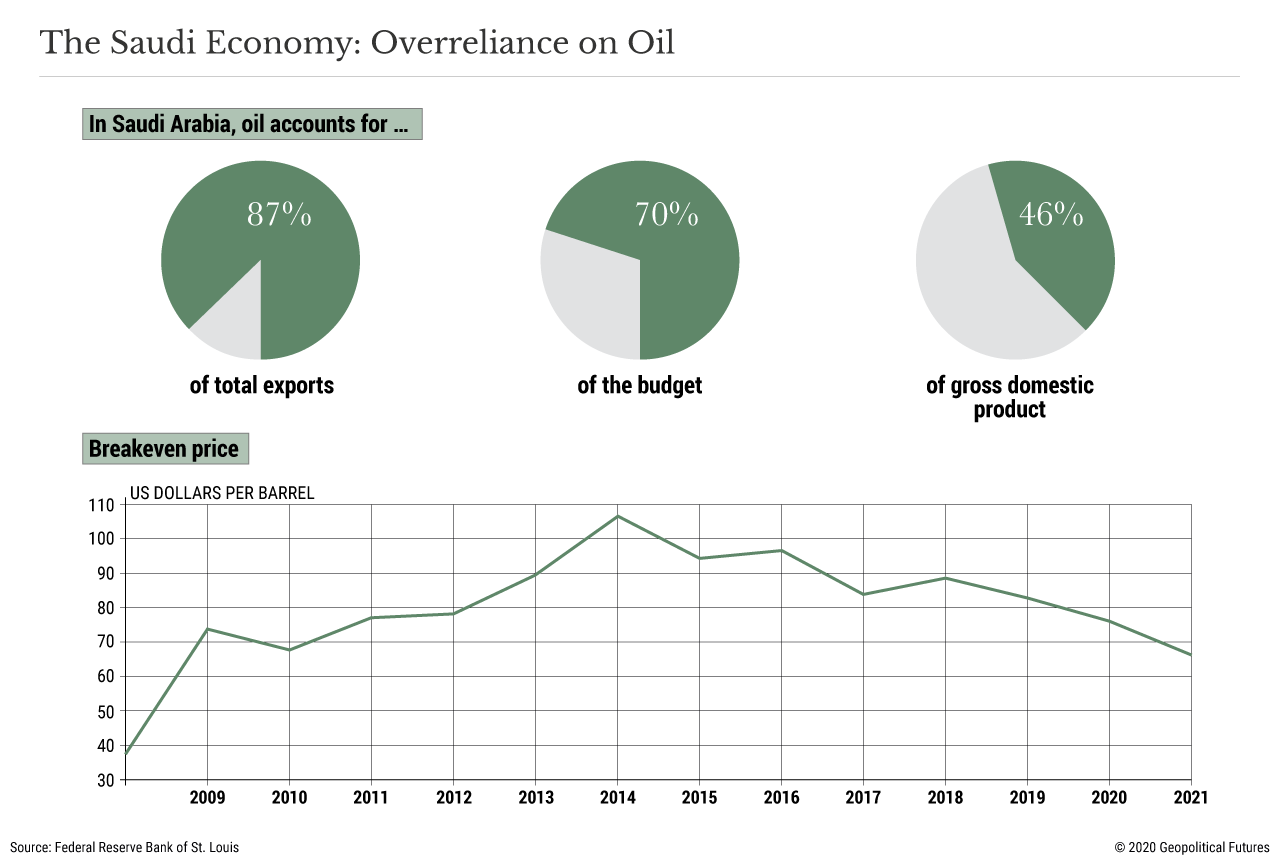

But the case for Neom is born of necessity as much as it is of ambition. Saudi Arabia has compelling reasons to search for new sources of revenue. Oil exports account for 87 percent of total exports, 70 percent of the budget, and 46 percent of gross domestic product. The advent of alternative energy sources such as electric cars is expected to dramatically reduce demand for hydrocarbons by 2025. Oil revenues are expected to drop by 33 percent in 2020 and 25 percent in 2021. The economy, therefore, is vulnerable to vagaries in the market, and always will be so long as it relies overwhelmingly on oil.

Even now, the budget deficit continues to grow, leading to further borrowing and excessive debt levels. The last annual budget deficit exceeded $100 billion. Saudi Arabia has lost more than one-third of its foreign reserves since 2014.

The most dramatic decrease occurred in March this year, with a $24 billion loss. The public sector is bloated, and the cost of maintaining it is high. The country’s expensive military expenditures are meaningless since it is unable to defend itself against foreign threats.

Economic diversification is a necessity because it reduces the financial consequences of fluctuating demand for hydrocarbons and unstable oil prices. Economic cities are Riyadh’s way of empowering the private sector and the long-sought-after solution to the dilemma of development.

Indeed, Neom intends to achieve what 10 previous plans tried and failed to: economic development. Riyadh’s first five-year development plan, which meant to transform the kingdom into a welfare state, started in 1970. The second and third development plans focused on building the infrastructure of economic development.

From the fourth through the ninth development plans (1985-2014), Saudi Arabia emphasized domesticating the workforce and focusing on human resource development. Government efforts encountered resistance because of public preference to seek employment in the public sector and aversion to manual or skilled labor and any position that assumed responsibility for making decisions.

The 10th development plan (2015-2019) set the stage for initiating the Neom project. It outlined the intention of transforming the kingdom into an international logistic center and launching grand economic initiatives without compromising Islam’s foundational values and tenets. In keeping with growing public demand and international pressure for political change, the plan paid lip service to the importance of citizenship and national belonging, strengthening the principles of justice and equality, and protection of human rights in accordance with Sharia law.

The 10th plan built on the principles of previous plans – that is, the exploration and development of economic diversification opportunities, investment in less water-intensive crops, development of a fisheries sector, and increasing human resource efficiency – though it differs in that it calls for the spread of information throughout the population, the activation of the role of economic cities, and the return of migrant capital to invest in productive sectors.

It is also, notably, built on ideas introduced in the seventh and eighth development plans, which recognized that cities could create the economic development Riyadh needs. This is embodied in the creation of King Abdullah Economic City, north of Jeddah, in 2005 at an estimated cost of $100 billion. The blueprint of the project included the construction of a container harbor and an industrial valley and the expectation that it would create 1 million jobs.

Other planned economic cities in the Northern Borders province and Jizan region concentrate on agriculture, food canning, vocational training, and storage. The government proposed that the economic cities in Mecca and Medina serve pilgrims in undertaking religious rites and providing high-end shopping. But these cities have either stumbled or atrophied, making Neom all the more consequential.

Science Fiction

Neom is a high-tech project that intends to provide advanced IT solutions. But its success is questionable in a country that scores low on the key indicators of a knowledge-based economy: skilled labor, incentives and motivation. Jamal Khashoggi, for example, was critical of Salman’s megaprojects, calling on him to launch smaller projects for the poor in Riyadh and Jeddah instead of complicated endeavors that don’t benefit local workers. He was killed inside a Saudi consulate in Istanbul in October 2018.

Saudi Arabia is also very censorial, curbing what its subjects are allowed to access via the internet and making sure that connections are always slow. The free and uninterrupted flow of information is crucial in developing independent and critical thinking that Saudi formal education views with disfavor. Neom cannot possibly thrive in a politically repressive and culturally closed environment.

Then there is the pesky problem of financing. Saudi Arabia’s finance minister recently announced that the country would implement painful measures to slash public expenses, given the dramatic decline in oil revenues due to the coronavirus pandemic.

The minister’s announcement led to a sharp decline of over 7 percent in the Saudi stock market. The unprecedented oil slump prompted Moody’s to downgrade Saudi outlook from stable to negative.

It is difficult to imagine that the Saudis can lure foreign investment to take part in Neom under the existing financial, social and political conditions.

And even if they can, Neom is like a mirage in the desert. The project does not differ fundamentally from similar initiatives in the United Arab Emirates and Qatar. The Port of Jebel Ali (Dubai) and the Hamad Port (Doha) are world-class seaports. The two countries have premier international airlines that Neom cannot dislodge.

Contrary to Saudi Arabia’s promotion of Neom as a site that straddles three continents, its location, surrounded by a vast swathe of barren desert, has no unique value. If anything, it would cripple the flagging Jordanian economy and destroy its tourism sector, as well as Egyptian resorts in South Sinai. Neom is just too much for the Middle East and way beyond what it needs.

The risks associated with the implementation of the project are high, and its outcome is unpredictable. The Neom scheme is unsustainable and potentially catastrophic. The introduction of flying taxis and robots capable of performing any task nullifies the claim that Neom would create millions of jobs. Saudi Arabia needs to import all the required technology to transform Neom into a reality, which is too costly to make the project feasible, especially with unclear benefits.

The plan does not benefit the local population that the government is coercing to vacate land needed for the project. Recently, the security forces killed a resident from the Huwaitat tribe because he refused to abandon his house and relocate.

In short, Neom is a project inspired by science fiction. It seems to have been influenced by the gated communities that American and British companies built in Saudi Arabia to keep their personnel disconnected from the locals. In November 2017, Salman ordered the arrest of hundreds of prominent Saudi princes and businessmen on the grounds of money laundering, embezzlement of public funds and corruption.

He subsequently announced recovering $50 billion to the state’s coffers, ostensibly contributing to development projects like Neom. He expected to get a similar amount before closing the Ritz-Carlton dossier.

There is little evidence that Neom is progressing except for the construction of five gigantic royal palaces serviced by a private airport and 10 helipads.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario