By: Ekaterina Zolotova

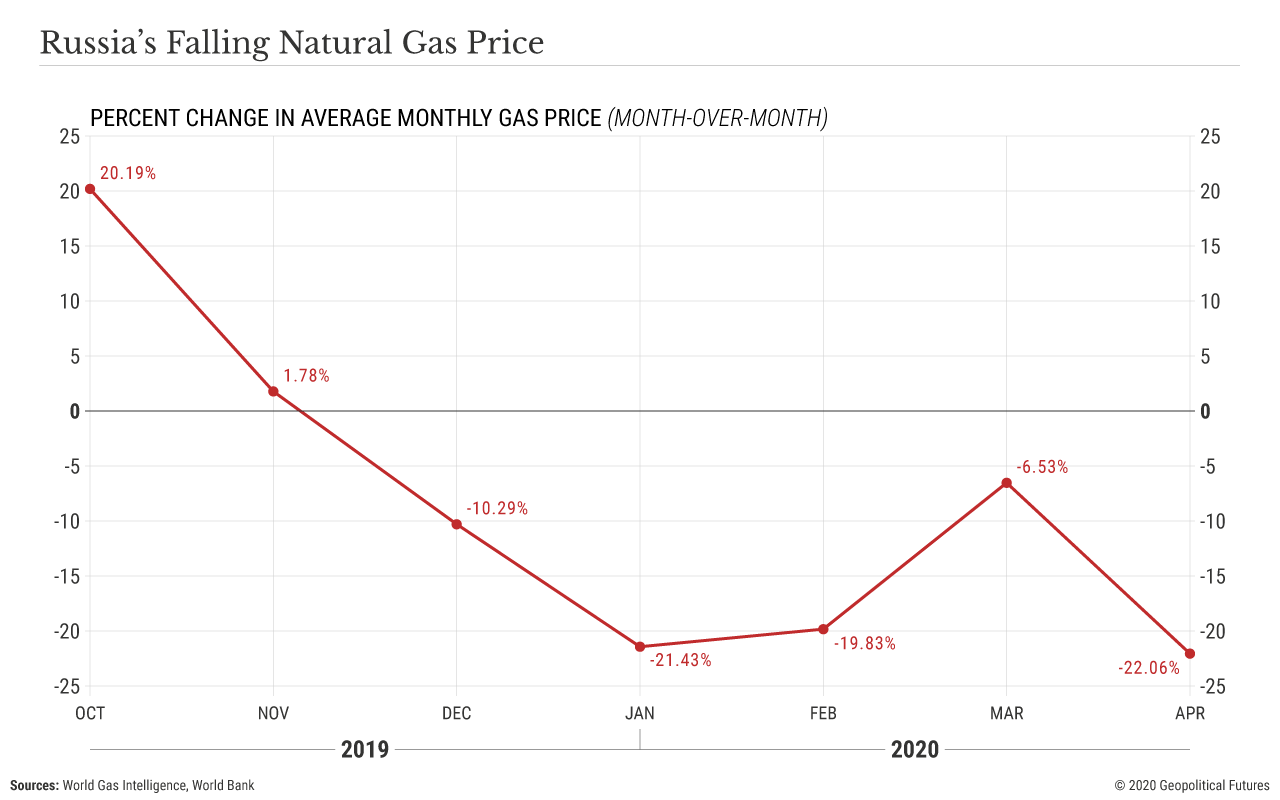

Low natural gas prices are straining Russia’s gas diplomacy. In the Netherlands, the European Union’s largest gas hub, prices are down to $52 per thousand cubic meters, which is a third what they were a year ago. However, for countries like Russia whose economies depend on energy exports and that employ fixed-price contracts, persistently low prices – a product of fluctuating oil prices, growing liquefied natural gas consumption, a dearth of storage facilities and plummeting demand due to the coronavirus pandemic – are pressuring energy companies to revise prices downward.

Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko recently said that his country pays $127 for Russian gas, while Europe pays less than $70. Armenian officials have also called on Russia to reduce prices. Even Kyrgyzstan, which does not consume much gas, asked Russia to adjust due to the difficult economic situation caused by the pandemic.

This puts Moscow in a tough spot. On the one hand, it needs stable and higher prices to keep its own economy afloat at this difficult time. On the other hand, it needs to satisfy the allied republics that make up its buffer zone and are part of its ambitious economic integration project, the Eurasian Economic Unión.

The formation of a single gas market is an important strategic step forward for the post-Soviet countries that constitute the EEU. Gas is a basic resource for most of them. For example, at 62 percent, it is the largest source of energy consumed in Belarus. It is 55 percent of the energy consumed in Armenia, and 53 percent in Russia.

But there are only two counties in the bloc that produce gas: Russia – by far the largest supplier – and Kazakhstan. The other three member states, Armenia, Belarus and Kyrgyzstan, do not produce gas domestically, and thus not only do they depend on foreign supplies – they depend on Russian supplies.

In a single gas market, the general formula for the formation of a gas tariff within the EEU would need to be implemented, and a system of free gas flow among members would be created. Most important, import-dependent countries would be able to buy gas at a lower price. At the moment, Russia’s average gas price is $55. Belarus, however, pays $127, and Armenia and Kyrgyzstan pay $165, according to their contracts for 2020. Even Kazakhstan is considering purchasing Russian gas for domestic consumption and exporting its own gas to China.

Moscow understands that it needs to ensure that EEU membership provides economic benefits to its members. And Russia itself benefits from the union – a common energy market would likely cement and strengthen Russia’s near-monopoly position as an energy supplier to its closest partners, but even more fundamentally, the EEU restores to Russia much of the regional influence that it has lost since the Soviet Union's collapse.

But from Moscow’s perspective, the other EEU member states should be satisfied with stable access to Russian gas, whereas Russia’s partners want preferential prices as well. (In fact, they argue the price they pay for Russian gas should be similar to what Russian domestic consumers pay.)

Sooner or later, Russia will have to make some concessions and unify gas tariffs within the bloc. And Moscow admits as much: The country’s long-term energy strategy indicates that it plans to align prices, but only by 2025. This has not yet been agreed among the EEU countries; Russia will discuss projects and sign joint statements, but it has abstained from making tangible proposals on price regulation until the rest of the union accepts deeper integration (for instance, a single budget and tax system, according to comments made by Russian President Vladimir Putin on Tuesday).

And on the subject of EEU integration, the lynchpin for Russia is Belarus. Minsk for years has balanced between Russia and the West, and Belarusian attempts to diversify its oil supplies have upset the Kremlin. If Belarus starts to think about greater market diversification and deeper cooperation with the West at the expense of ties with Russia and the EEU, the Kremlin risks losing the buffer zone that separates NATO troops in Poland from Russia’s borders. In addition, with construction of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline to Germany delayed, Belarus remains an important hub for the transit of Russian gas to Western Europe and Kaliningrad.

This is why Russia is in no hurry to offer lower gas prices until Belarus agrees to closer integration. The Kremlin said the price will be determined after the development of roadmaps toward implementation of the Russia-Belarus Union State. Until the Kremlin gets what it wants from Minsk, it will not accelerate moves toward a common gas market or provide more favorable conditions to other EEU countries, lest Belarus demand similar conditions.

Russia’s need to strengthen and solidify its influence in post-Soviet countries is not always consistent with state-owned company Gazprom’s pursuit of profits. Gazprom is Russia’s largest gas supply company and has a monopoly on gas exports. The Kremlin wants to ensure the stability of Gazprom and expand the firm’s trading operations and projects. And Belarus, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan are important customers and/or links in the distribution network for Gazprom.

But Gazprom wants to be equally profitable selling gas at home and in the EEU, especially as the economy is shrinking. After Rosneft, Gazprom is the second-largest contributor to Russia's budget. In 2018, its tax payments reached 2.7 trillion rubles ($37 billion), which was almost 15 percent of the budget's total tax revenue.

Because of the drop in demand resulting from the pandemic-induced economic slowdown and a relatively mild winter, Gazprom’s revenue and tax payments may shrink. At such low prices, delivering gas to the domestic market is more profitable than exporting it, because it avoids transit fees and related costs.

Though Gazprom is protected by take-or-pay clauses and fixed-price contracts, it ideally wants an export price close to $100 per thousand cubic meters. Current prices are significantly lower than Gazprom’s profitability point, which starts from $63 through Nord Stream 1, the cheapest route.

And there is another reason Russia does not want to move ahead with the establishment of a single gas market just yet. Doing so would entail setting common gas tariffs in the EEU. This would likely lead to lower prices for Armenia and Belarus but higher prices in the Russian market. A sudden, significant hike in domestic gas prices in a country where 53 percent of the energy consumed comes from gas, the economy is slowing and companies are struggling to stay afloat would lead to significant social dissatisfaction.

The Kremlin thought that it would have more time before 2025 to adapt internal gas prices to the external environment and create the basis for further integration within the EEU. But the economic slowdown and uncertainty is forcing Russia to work with a shorter timeline. Russia has some external circumstances working in its favor.

For instance, Belarus may temper its demands for gas price reductions once its Astravets nuclear power plant comes online. The plant, which was built by a Russian contractor and with Russian credit, is expected to significantly reduce Belarus’ gas consumption.

For its part, Kyrgyzstan uses alternative energy sources such as coal and oil and thus can afford to be patient. Armenia has no cheaper sources of gas than Russia; Iranian gas is much more expensive, at $220. Altogether, Russia believes it can delay the discussion on gas tariffs to a more favorable time, but the economic fallout from the pandemic may force the Kremlin to make strategic choices earlier than it had expected.

At the very least, it will have to walk a thin line between its strategic needs and the needs of its economy.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario