King Dollar Is a Deadly but Dangerous Trump Card in U.S.-China Fight

Powerful weapons can create blowback if the wielder isn’t on steady ground

By Nathaniel Taplin and Mike Bird

Limiting the ability of China’s banks to do business in dollars would be destabilizing to say the least. / Photo: jose luis gonzalez/Reuters .

Some aspects of the U.S.-China breakup will be expensive for America, but in finance China clearly has more to lose. The dollar remains the beating heart of the global financial system and control of the dollar-funding system is a formidable tool to punish adversaries.

Still, overuse of that tool by Washington carries long-term risks, which could be exacerbated by policy makers’ failures at home.

Curbing U.S. ownership of Chinese stocks has generated headlines but is more a matter of frustrating Beijing’s global ambitions than seriously damaging Chinese capital markets. The portion of China’s domestic A-shares held by overseas investors still amounts to only 3.5%.

The real bazooka for the U.S. would be sanctions against Chinese banks. Last year, three unnamed Chinese lenders were found in contempt of court over a probe into sanctions against North Korea, opening them up to the possibility of U.S. punishment. A proposed Senate bill also threatens penalties on banks that are complicit in undermining Hong Kong’s freedoms.

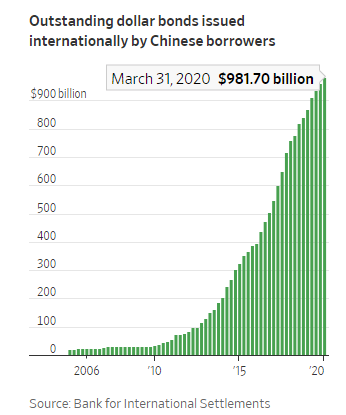

Limiting the ability of the country’s banks to do business in dollars would be destabilizing to say the least. Of the $2.215 trillion in international claims that China’s banks have overseas, 63% are denominated in dollars.

In the next two years, about $321 billion in U.S. dollar-denominated debt issued in China and Hong Kong will mature and may require refinancing. U.S. financiers, meanwhile, still have little meaningful exposure to the yuan.

Curbing Chinese banks’ access to dollars wouldn’t be cost free for the U.S., however. A sudden seizure in dollar-denominated trade finance for Chinese firms could plunge the world into an even deeper recession.

And while the dollar’s position at the center of global finance looks secure in the near-term, there are still long-term threats which—if unaddressed—could be exacerbated by the U.S.-China rivalry.

U.S. debt is attractive because it is safe, liquid and—compared with other developed economies—has for decades provided a decent yield. In the immediate savings-rich, deflationary post-Covid world, there is no reason to fear a shortage of buyers, even with rapidly rising deficits. Beijing is unlikely to sell its large holdings unless forced to: the resulting fall in the dollar would hit its exports at the worst possible time. And the Federal Reserve is once again adding to its holdings.

But over the long run, things could look different. A more divided, less efficient global economic system seems likely to be inflationary. And unlike euro debt, Chinese government bonds actually provide a decent yield: foreigners have bought about $200 billion worth since 2015. Meanwhile foreign buying of Treasurys has slowed. Foreign Treasury holdings have risen by just $652 billion, or 10%, since 2014 even though total public Treasury debt has risen about 30% since then. In the five years ending in 2014, foreign Treasury holdings rose by $2.5 trillion.

China’s creaky financial system could still fall apart, and the country faces myriad threats to its growth, from an aging population to a bloated property sector. Beijing will also need to prove it is committed to allowing bond buyers to sell in a pinch, given its history of tightening capital controls when trouble strikes.

But if China keeps growing faster than the U.S. and can establish a record as a reliable counterparty, more investors may begin to question why they should buy lower yielding U.S. debt—particularly those based in developing nations that already have China as their largest trading partner and may not be adverse to doing more trade in yuan.

China already does about 15% of its foreign trade in yuan. And weaponizing the dollar, as the U.S. has increasingly been inclined to do in recent years, risks harming its appeal as a haven asset.

All of this makes structural reforms to keep U.S. growth high in a more divided world—especially higher investment in science and education, immigration reform, and tighter trade links with friendly nations—all the more important.

Financial decoupling between the world’s two largest economies would undoubtedly punish the second-largest player far more than the top one—perhaps severely.

But in the long run, the best American offense is likely to be a good defense: reforms to address longstanding frailties at home which could undermine U.S. economic and military might.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario