By: Caroline D. Rose

Next month, a U.S. delegation will board a plane to Baghdad to discuss with Iraqi leaders the prospect of reducing Washington’s military footprint on Iraqi soil. It would have been an unthinkable idea at the beginning of the year, when U.S.-Iran tensions came to a head after the assassination of Qassem Soleimani, the leader of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.

Even then, the Iraqi parliament voted on a bill that would have sent the U.S. packing had it ever been executed. But where the parliament failed, the coronavirus pandemic, a mounting recession and global uncertainty may succeed in getting Washington to withdraw from the region – something it had tacitly wanted to do anyway, at least on its own terms – more quickly. Ready and waiting to capitalize on its departure is Iran.

Despite Iran’s own problems in managing the coronavirus outbreak, its foreign policy seems to be having a moment in the sun. Over the past three months, the IRGC and its Shiite proxies have taken advantage of the international distraction and Washington’s absence to launch successive attacks on American targets.

Indeed, it appears as though Iran is getting what it wants: a path to project power in the Levant. But it won’t be that easy for the IRGC. U.S. force reduction will not necessarily translate to sanctions relief or give way to an unobstructed march to the Mediterranean. Plenty of constraints remain, even in the absence of the U.S.

Cutting the Cord

Since 1979, the Levant, particularly Iraq, has been a battleground for political and military influence in the Middle East. Boxed in by the Zagros Mountains and with difficult maritime access due to the Strait of Hormuz, Iran crafted a policy by which it projects power abroad primarily through proxy forces to its west. And since the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the United States has stood in its way.

Fast-forward to 2020. As the world tried to make sense of the ongoing pandemic, Iran resumed its attacks on the U.S. and its anti-Islamic State coalition partners. Just this week, the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad’s Green Zone was struck by a rocket, very likely launched by an IRGC-aligned militia.

Iran also upped the ante in the Persian Gulf. In April, 11 Iranian fast boats harassed a warship from the U.S. 5th Fleet, edging so close that the U.S. threaten to shoot the Iranian ships out of the water if they came within 100 meters again. U.S. aggression has proved almost entirely rhetorical. Washington has long wanted to leave; Iranian attacks and a global viral outbreak gave it an excuse to cut the cord.

The Pentagon thus began pulling forces from coalition bases, reducing troop counts or withdrawing altogether. In just four months, the U.S. has drawn down from more than five bases, including the strategically important base in al-Qaim, which straddles the Syria-Iraq border.

And instead of beefing up American operational presence in the Persian Gulf – something you may expect to happen in the wake of maritime provocations – the Pentagon signaled a large-scale plan that actually reduces the official number of overall personnel in the region, and is reportedly considering scaling down the 5th Fleet’s presence in the Persian Gulf by one aircraft carrier strike group, withdrawing two Patriot missile defense systems, air defense systems and jet fighters from Saudi Arabia, while mulling a reduction in the Multinational Force and Observers peacekeeping mission in the Sinai Peninsula.

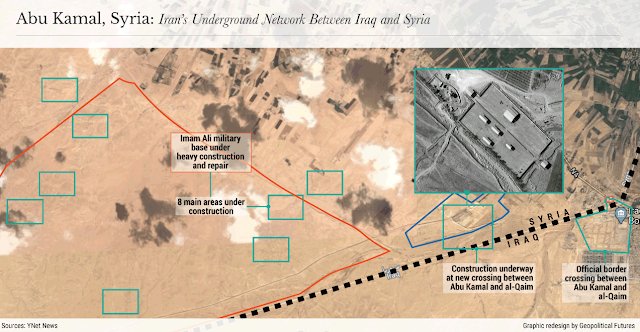

Iran has acted quickly to increase its military hold in Iraq and Syria, beefing up its defensive presence and smuggling capabilities along the al-Qaim highway. Recent satellite imagery from ImageSat International shows an Iranian tunnel project under the Imam Ali military base in Abu Kamal, Syria, on the Syria-Iraq border.

Tunnels between pro-Iran proxy strongholds in western Iraq and IRGC locations in eastern Syria strengthen Iran’s strategy to expand its influence west, allowing IRGC forces and their proxies to store vehicles, shelter personnel, transport advanced weapon systems, and smuggle arms from the east to the Mediterranean.

Related, Iran has been engaging more in the Israel-Palestine conflict. With reduced American presence in Sinai – the traditional buffer between Israel and Arab countries – Iran has begun rallying Palestinian militant groups such as Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, both sympathetic to Iran, to confront Israel, all while increasing its own military exchanges with Israel through Hezbollah and cyberattacks on Israeli water installations.

Remaining Challenges

And yet, Iran isn’t without challenges. In light of the drawdown, Saudi Arabia, for example, has begun to rethink its Iran strategy. With an oil price crisis, creeping global recession and sudden withdrawal of Patriot systems, Riyadh wants to find a quick, cost-effective way to keep Iranian aggression at bay. Saudi officials have therefore sanctioned talks with Iran, with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman nominating Iraq’s new prime minister to act as mediator.

Even so, discussions between the two have long proved fruitless, and diplomacy should be seen only as a measure of first resort. Indeed, Riyadh has already made plans to replace the two U.S. Patriots with its own missile defense system, increase military training exercises with U.S. advisers and secure a Boeing contract of 1,000 air-to-surface and anti-ship missiles – all to curb Iranian attacks.

Israel, too, will be one of Iran’s largest impediments. Already it has increased strikes on IRGC and Hezbollah equipment storage locations and bases in Syria by sevenfold. It has also intensified its border patrols, destruction of cross-border tunnels, and cyberattacks on Iranian entities.

This week alone, Israel conducted a cyberattack on Iran’s Shadi Rajaee port facility, causing a major backlog in terminal arrivals and maritime traffic. With reduced U.S. presence in the Levant, Israel will likely up the ante in attacks on IRGC factions in Syria and Lebanon. (Notably, Israel and the Arab Gulf states have entered a quiet alliance against Iran, sharing intelligence and engaging in back-channel talks.)

Just as daunting are the internal challenges Iran will face in sustaining the political and military influence it’s built in the region. Since the fall of 2019, massive political movements have emerged in Lebanon and Iraq protesting economic conditions, unemployment, corruption and rising inflation. A key feature of these protests has been mounting resentment of foreign interference – particularly by the U.S. military and Iranian proxies.

In Iraq, elements of the nationalist Sadrist movement have been especially loud in their opposition to Iran, with some even attacking Iranian consulate buildings and IRGC-sponsored militia headquarters. In Lebanon, much of the anti-Iran sentiment has been directed at Hezbollah, a major beneficiary of Iranian political, military and financial support (even though sanctions have put a dent in aid in recent years). With the U.S. withdrawn, protesters will hone in on Iranian intrusion even more.

Syria is perhaps even more problematic. The country has been one of Iran’s strongest Arab allies for decades, and its presence in Syria depends overwhelmingly on President Bashar Assad remaining in power. There are signs, however, that Iran is struggling to keep influence there. Rumors have begun to circulate that Russian President Vladimir Putin, another staunch Assad ally, is unhappy with the Syrian government.

Since 2015, Moscow has helped Assad stay in power, providing aid, airpower and infrastructural investment that has allowed the regime to regain a majority of rebel-held provinces. If Russia decides its gambit in Syria is no longer worth the cost, either withdrawing its forces or looking to an alternative source of power to unify the country, Iran is at risk of losing its proxy influence in Syria.

Then there is the U.S., which will still have plenty of in-theater capabilities in the Middle East. The U.S. 5th Fleet and air defenses aren’t going anywhere. The Air Force still maintains multiple squadrons of fighter jets in Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and other undisclosed locations.

And though the U.S. is reducing its physical footprint in the Middle East, it will increase its reliance on economic statecraft – sanctions, oil embargoes and foreign aid – as its primary mechanism to pressure Iran into financial and political collapse.

Washington has already proposed extending the U.N. arms embargo on Iran, plans to sanction Iranian officials and companies that support the Assad regime under the Caesar Act, and is considering a blockade on Iran-Venezuela mutual assistance over recent Iranian oil shipments.

So while Iran may seem well suited to take the reins of the Middle East when the U.S. is away, the reality is more difficult. Its recession has gotten worse. Oil exports have crashed. The rial has been put on life support. The cost of living has skyrocketed. And there is a network of enemies and tenuous friendships that stand in its path to the Mediterranean.

The U.S. departure from the Middle East may not create a proverbial power vacuum, but it will dramatically shift the regional balance of power in ways that will constrain Iran.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario