Apparent recovery from coronavirus shutdowns is allowing China to project strength, but it isn’t quite what it seems

By Nathaniel Taplin

A job fair in Wuhan in China’s central Hubei province in April. / Photo: Xiao Yijiu/Zuma Press .

China’s economy was first out of the gate after coronavirus lockdowns, which might be one reason for Beijing’s recent tough diplomatic stance. But a closer look at the nation’s labor market raises some questions over that progress.

China’s urban unemployment survey showed just 6% of respondents out of work in April, against nearly 15% in the U.S. But most economists don’t believe these two measures are directly comparable, in part because China’s measure misses migrant workers who return to rural areas during downturns.

ANZ Bankestimates that total unemployment and underemployment in China—including involuntary part-time workers and those not actively seeking jobs—was likely around 16% in April. Consulting firm Gavekal Dragonomics thinks there were 60 million to 100 million workers away from their jobs in March and April, or 11% to 20% of nonfarm workers.

Those numbers still look better than their equivalents in the U.S., where 22% of workers in April were unemployed, underemployed or not seeking work. But the difference no longer looks quite so stark.

And the hit from collapsing trade will make it difficult for many of those underemployed Chinese migrants to get back to full employment soon. China’s manufacturing purchasing managers index for May, released Sunday, showed new export orders still falling at comparable rates to early 2009, during the depths of the global financial crisis.

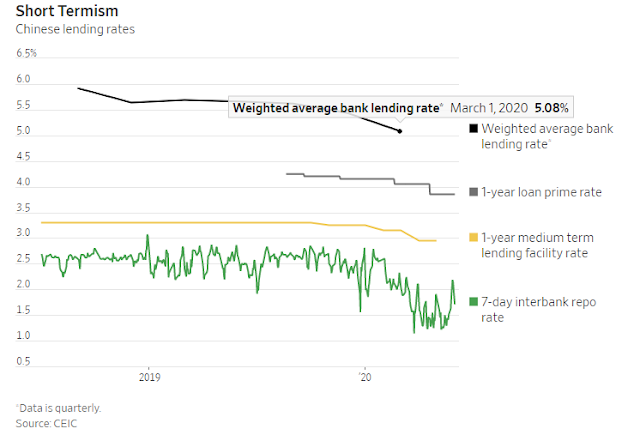

One implication of all this is that Chinese monetary policy needs to get looser, particularly since heavy government-bond issuance has begun pushing bond yields up again in recent weeks. Using a regression model based on employment growth and inflation, ANZ finds that China’s weighted average bank lending rate—last reported at 5.08% in the first quarter—should be around 0.6 percentage points lower.

A medical worker taking a swab sample for the coronavirus from an employee at a factory in Wuhan on May 15. / Photo: str/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images .

China’s short-term interbank lending rates have already fallen sharply this year, but its benchmark one-year bank lending rate, the loan prime rate, is only down 0.3 percentage points. Rates on the central bank’s key one-year lending facility for banks, which are meant to feed into the loan prime rate, have also only fallen 0.3 percentage points.

Chinese banks and workers still need help, and all those government bonds need buyers. One way or another, that means more support from the central bank—preferably targeting medium rather than shorter maturities. Another bubble in short-term interbank lending, like the one the central bank deflated in 2017, is the last thing China needs.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario