By: Ekaterina Zolotova

The Russian economy is in trouble. As in virtually every country on the planet, economic activity has slowed due to the coronavirus pandemic. The subsequent lockdown has deprived the country of 17.9 trillion rubles (nearly $228 billion), according to Russia’s National Rating Agency, and Moscow expects as much as a 5 percent contraction for 2020.

More than 15 million people could lose their jobs; those who don’t could see their incomes fall by 5 percent if the lockdown continues for another 2-3 months.

Russia will be slow to recover. The speed and effectiveness of efforts toward that end will depend on how much Moscow can prop up the economy. But herein lies the problem. Financial assistance comes from a state budget that has taken a beating in the slump in oil prices, on which the Russian economy so heavily relies.

Indeed, raw materials such oil, natural gas, coal, metals and other minerals accounted for nearly 14 percent of Russia’s gross domestic product in 2018 — about 50 percent more than they did in 2014. In 2018, mining constituted 39 percent of total industrial production; in 2010, it accounted for just 34 percent.

The share of oil and gas revenues in the budget almost doubled from 2016 to 2018, peaking at about 46 percent. This is separate from Russia’s National Welfare Fund, which is funded by additional federal budget revenues from oil and gas. Money from the sale of oil abroad in excess of the base price is sent to the National Wealth Fund, and when the size of the liquid part of the fund exceeds 7 percent of GDP, Moscow can use it for new investments in projects.

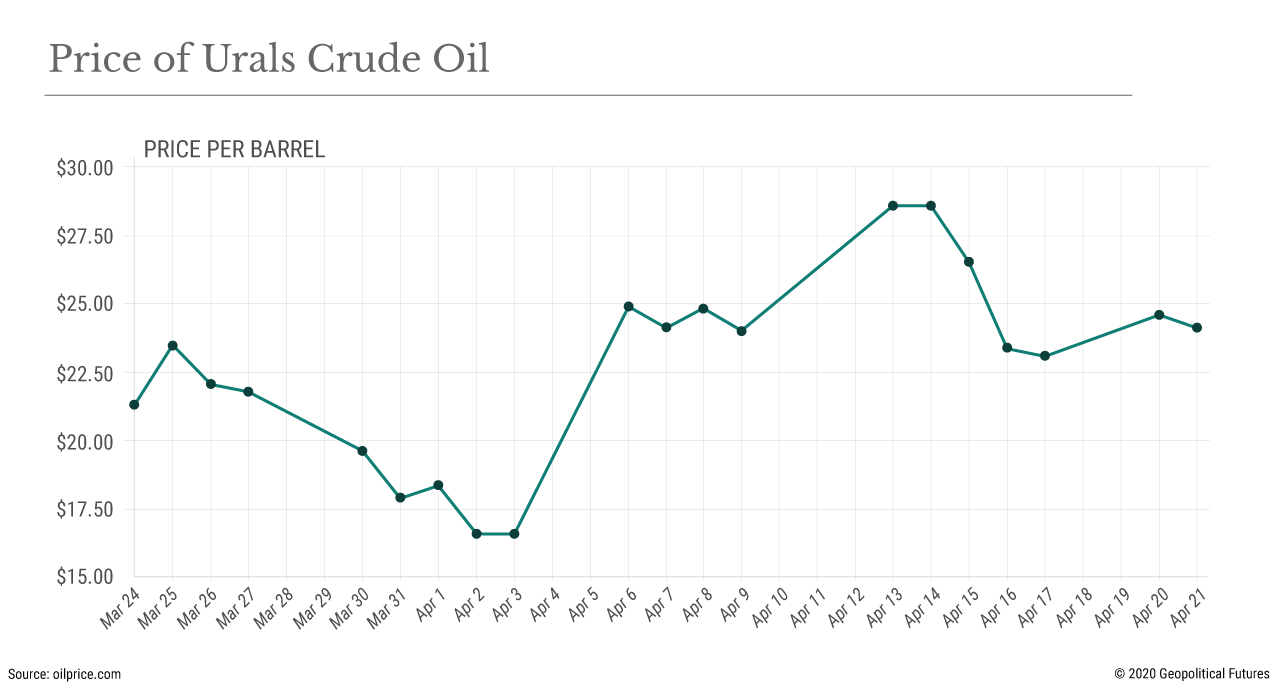

That’s all good and well when oil is expensive, but the pandemic has sent prices spiraling downward. Due to high supply and weak demand, the price of Urals fell to $11.50 per barrel in April, the lowest it has been since 1999 and below the “risk scenario” tier set by the central bank.

OPEC’s failure to reach an agreement to stabilize prices only made matters worse; in fact, Russia and Saudi Arabia even decided to increase production.

A reduction agreement was finally reached in mid-April, whereby OPEC+ members would lower production by nearly 10 million barrels per day. That’s not nothing, but it has yet to stabilize prices as its authors had hoped.

It’s a problem that is somewhat unique to Russia. While many countries are rightly concerned about insufficient storage capacity, prices are Moscow’s utmost priority.

Partly this is because Russia’s oil industry is structured differently from that of other exporters. Energy is generally secured by long-term contracts in places like Europe and China and delivered through systems that Russia owns, primarily via pipelines linked to European and Belarusian refineries.

Sometimes this leads to some surprising market behavior. For example, while futures contracts dived toward zero in the U.S., the low price of Urals led to increased exports. China reportedly purchased an unprecedented 1.6 million tons of Russian oil in April, while Belarus announced in early April that it wants to buy 2 million tons (priced at $4 per barrel).

Of course, this wasn’t especially profitable for Russia, but Russia was at least able to offload a bunch of excess oil onto the market, replenish Belarusian oil refineries and partially mitigate the brewing conflict between the two over energy prices.

But this is just a short-term benefit. Exports are inherently limited by demand, and demand is low among Moscow’s primary buyers. If that doesn’t come up, it will be impossible to finalize new contracts.

Moreover, production will be dictated by the new OPEC+ agreement, so, assuming Russia adheres to it, it will be impossible to adjust prices by adjusting production. Oversupply will continue to hamstring markets and producers for the next few months, perhaps none more so than Russia.

The reduction in export earnings due to price volatility is a drain on the Russian economy.

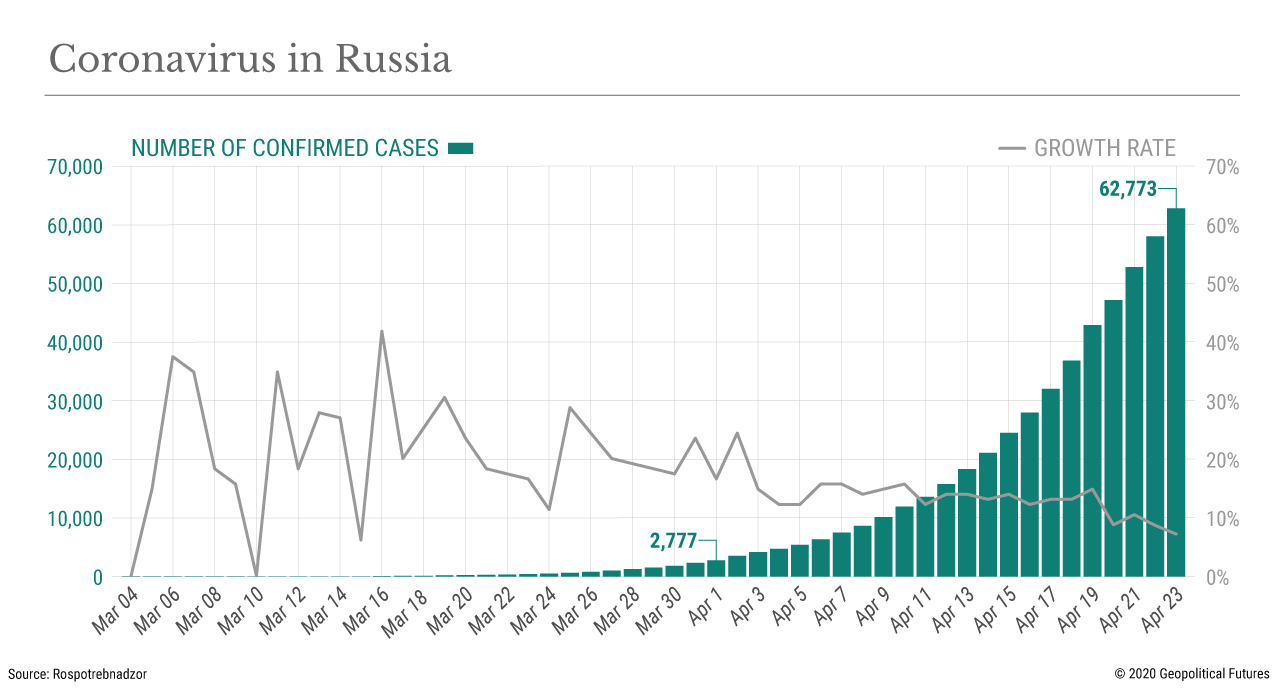

Russia needs the income from oil exports to mitigate the effects of the coronavirus on the economy. Despite strict quarantine, the number of infections in Russia continues to grow.

The government is not planning to ease the lockdown, and in fact is discussing extending it until mid-May.

To cope with the strain of a prolonged lockdown, the government will likely start to think about a new economic assistance package to prevent more severe damage and to eventually lift the economy out of the crisis. Moscow has already adopted two support packages totaling 2.1 trillion rubles, about 2.8 percent of GDP.

These include some help for small and medium-sized enterprises as well as assistance for vulnerable segments of the population. President Vladimir Putin also proposed allocating 200 billion rubles to the regions to ensure their "sustainability and balanced budgets,” and announced the need to spend 23 billion rubles to support airlines.

The challenge is where to find the funds for a new round of economic measures at a time when low oil prices are sinking the federal budget. The 2020 budget was drafted so that the federal government would be in surplus if oil prices were above $42.45 per barrel. According to reports, the latest government forecast, however, was for a federal budget deficit of 5.6 trillion rubles instead of the previously planned 900 billion-ruble surplus.

The pandemic has depleted not only tax revenues from economic activity but also revenues from the mineral extraction tax, which accounts for up to 50 percent of the federal budget (46 percent in 2019). According to Ministry of Finance calculations, in March alone, the total volume of lost oil and gas revenues amounted to 22 billion rubles.

And because of the fall in oil prices, the Russian budget in April will receive less than 55.8 billion rubles in oil and gas revenues. In total, the government is already estimated to have lost 4.2 trillion rubles in taxes, insurance premiums and fees.

The new budget revenue projection is 15.2 trillion rubles, while planned expenditures are 20.8 trillion rubles — compared to an initial budget that foresaw 20.6 trillion rubles in revenues and 19.7 trillion rubles in spending. The Ministry of Finance planned to prepare a new version of the financial plan but the process has been delayed, so these estimates may go even lower.

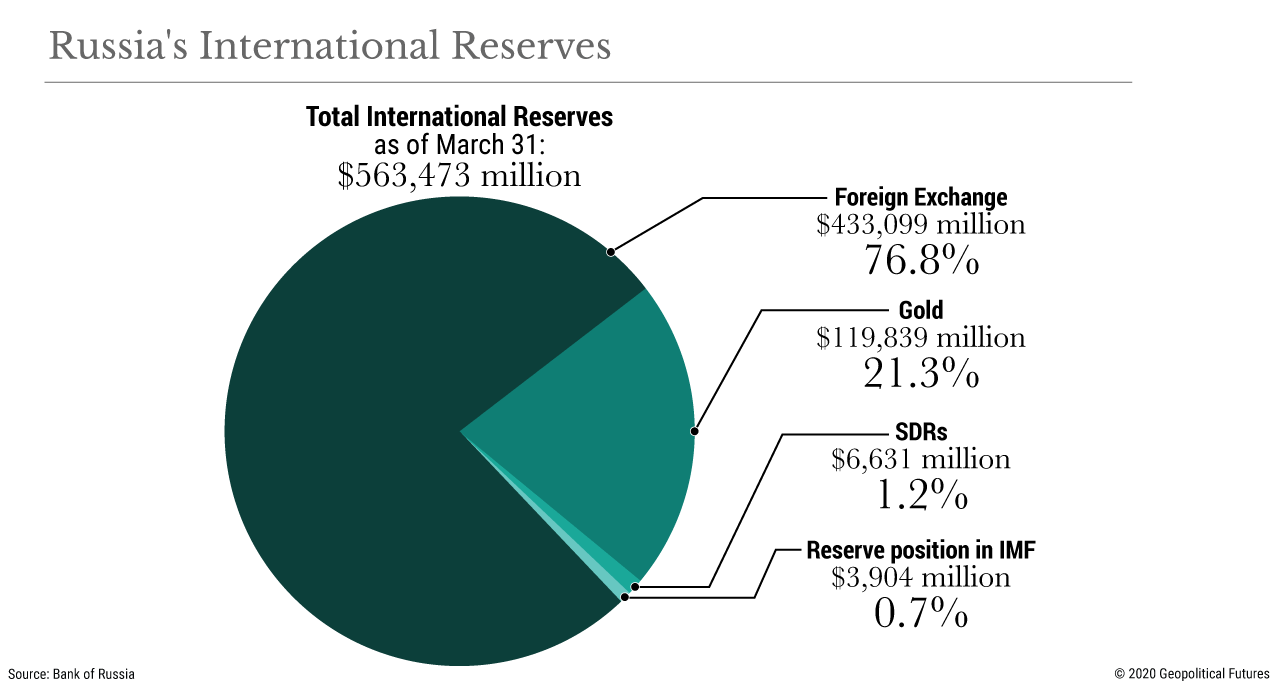

In early April, the Russian government announced that it had accumulated reserves in the amount of 18 trillion rubles, but low oil prices complicate the use of other foreign currency deposits. The government’s liquid assets — that is, ruble and foreign currency deposits — total 15.3 trillion rubles, while regional governments have an additional 2.4 trillion rubles.

Separately, the National Wealth Fund (NWF) held 12.85 trillion rubles at the beginning of April, equal to 11.3 percent of GDP. The government plans to use part of the NWF to support the economy and social programs, which may reduce the fund to 6.5 percent of GDP, but this is the most that the state can afford.

According to the Kremlin’s calculations, if oil prices stay low and the government continues to rely on the NWF, the fund would be empty before 2024. This would put the government in a very unstable position. Since the NWF is also used to fund some social programs, in the event of a deeper recession, the government would lose the ability to support, for example, pensioners and the unemployed, which could lead to massive social discontent.

Besides these concerns, the Kremlin’s ability to use these funds from the NWF is limited by budgetary rules. When oil prices are below $42.40, the law requires the Ministry of Finance to sell foreign currency reserves to compensate for the missing revenues from the oil and gas sector.

In addition, injecting oil money into the economy could increase the ruble’s dependence on oil.

The Kremlin is not planning to use reserves to finance the projected budget deficit: The government will take only 2 trillion rubles from the NWF, and more than 1 trillion rubles from other sources, and the rest will be borrowed in the market. In 2020, the Ministry of Finance expected to borrow 1.7 trillion rubles in the domestic market and 207 billion rubles ($3.15 billion at the exchange rate at the time) in the foreign market.

Faced with a crisis in oil markets, Russia is not ready either to take additional measures to stop the fall in oil prices or to assist the economy further. Although the government is confident, or is pretending to be confident, that it has enough resources to withstand any crisis — Russia has accumulated huge reserves and has very low external debt — the fact remains that a barrel of Russian Urals is below $20, and supporting the economy has already cost trillions of rubles.

With or without a lockdown, the Russian economy will have to revise its ambitions at current oil prices.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario