By: Phillip Orchard

For a brief moment in mid-February, the South Korean city of Daegu looked like it was heading the way of Wuhan, the Chinese megacity at the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. In two weeks, the number of detected cases in Daegu jumped from a handful to more than 6,000. (More than 1,200 of those cases were members of a single megachurch that had been sending missionaries to Wuhan.)

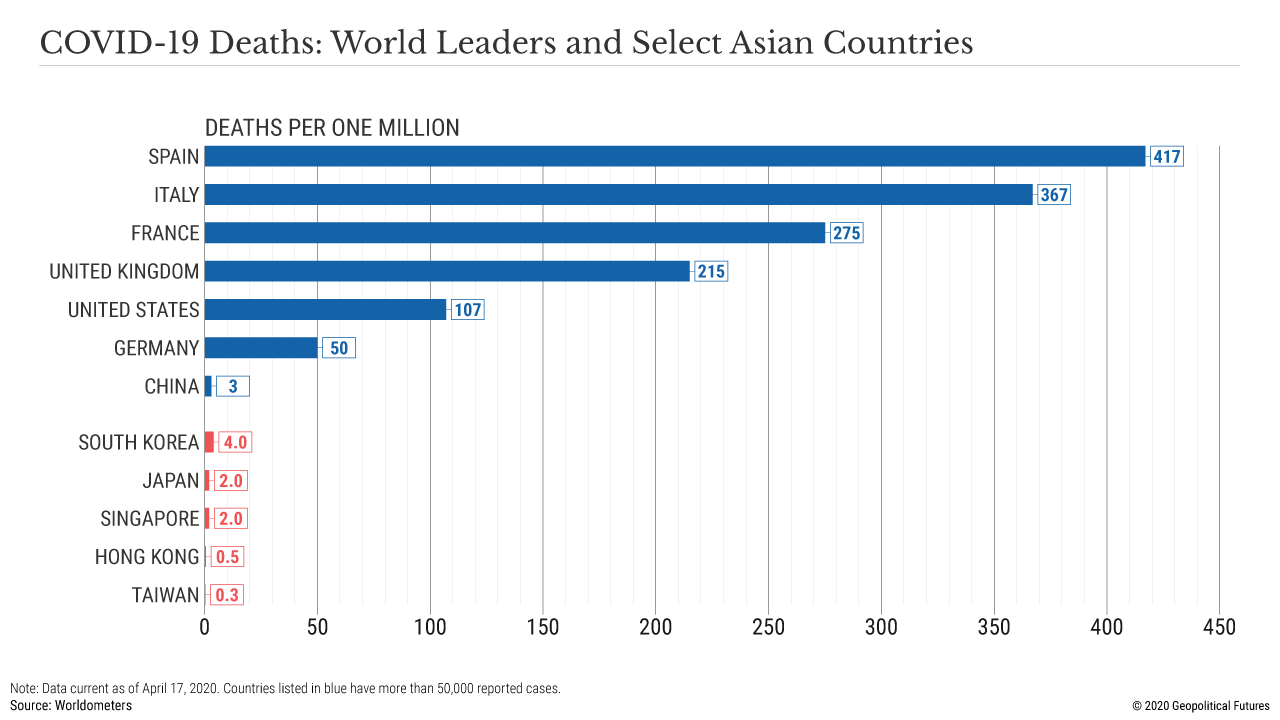

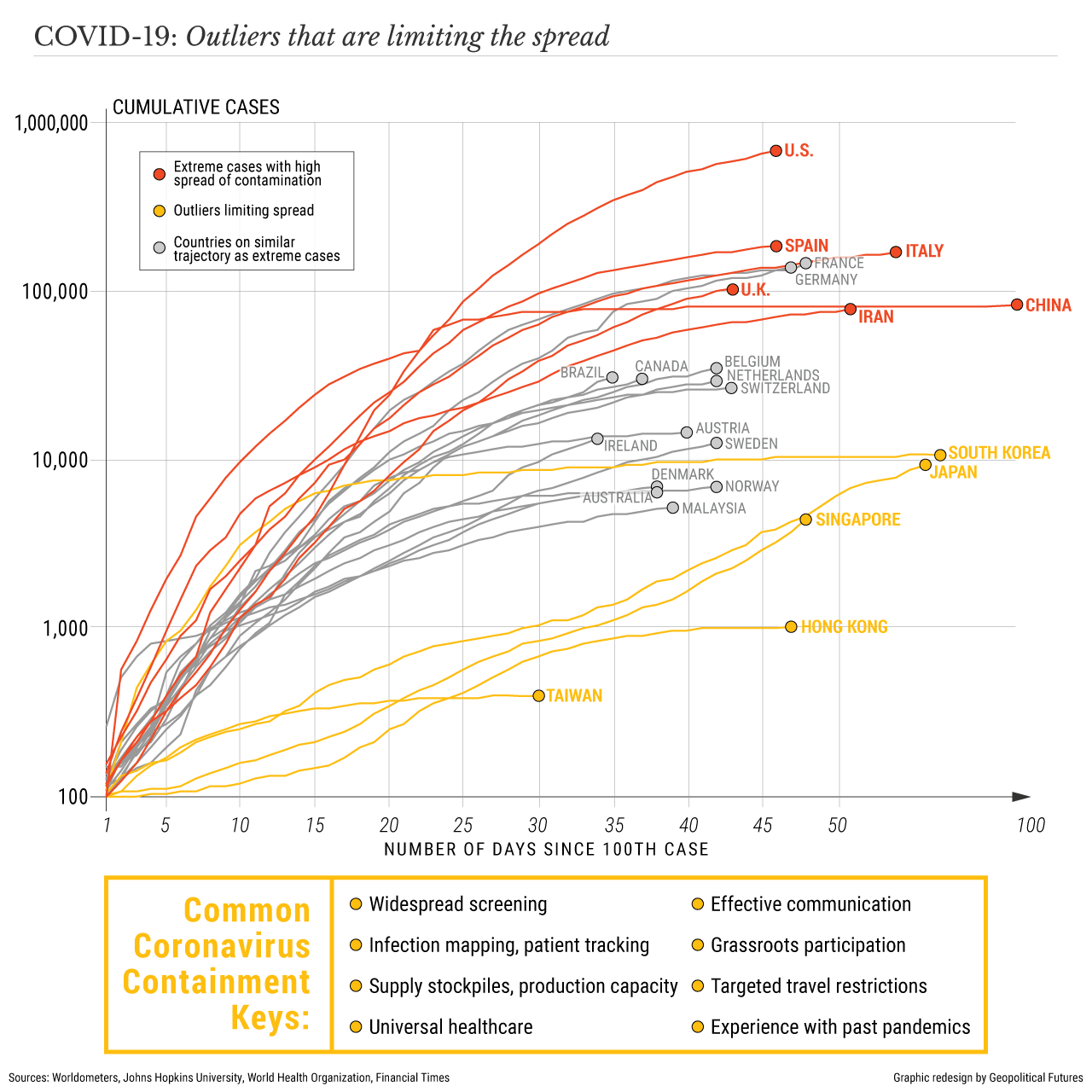

This figure may seem quaint today, but at the time it made South Korea the only other country on China’s road to “viralgeddon.” Since mid-February, though, South Korea has become proof that the virus can be brought to heel without a cure, a vaccine or endless draconian quarantine measures. By April 6, new daily cases had dropped below 50, and they have stayed there. Just 230 South Koreans have died.

Remarkably, the government was able to crush the curve without completely shutting down life inside the country. Office buildings, shopping malls and restaurants often remained open. Churches started resuming services by Easter.

And, on Wednesday, close to 30 million people, nearly two-thirds of the country’s eligible voters, felt confident enough in the government’s containment measures to show up at the polls and give President Moon Jae-in’s Democratic Party a landslide victory in parliamentary elections.

This means that, for his remaining two years in office, Moon can push his ambitious agenda with the backing of a near-supermajority in the National Assembly and a hearty public mandate. And, absent a COVID-19 revival, he’ll be governing a country that would seem to be uniquely well-positioned to leverage its epidemiological success into geopolitical influence.

However, South Korea will remain subject to the underlying forces that have historically limited its options, particularly as its all-important alliance with the United States comes under further strain.

How South Korea Dominated the COVID-19 Outbreak

The odds were stacked against South Korea in its fight against the coronavirus. An average of 16,000 visitors from China arrived each day in 2019, with more than 50 direct flights arriving from Wuhan in both December and January.

More than 81 percent of South Koreans live in urban areas, and the country has one of the highest public transportation usage rates in the world. Nearly half the South Korean population is older than 45, the age group that accounts for more than 90 percent of COVID-19 fatalities worldwide.

But this vulnerability to pandemics is in large part why the country responded to the coronavirus so successfully. Like others in East Asia that have managed the outbreak relatively well — Hong Kong, Singapore and gold medalist Taiwan — South Korea honed its skills the hard way during past outbreaks.

The country saw just three cases during the 2003 SARS outbreak, which left the government overconfident and underprepared for the 2015 arrival of MERS, COVID-19’s less infectious but deadlier cousin. That virus infected 182 South Koreans and killed 38 — the highest levels outside Saudi Arabia — and contributed to the defeat of former President Park Geun-hye’s conservative Liberty Korea Party in parliamentary elections the following year.

As a result, this time around, Seoul acted quickly and aggressively. As soon as the Daegu cluster was detected, the government isolated the city, forced politically powerful churches (which have proved to be “super-spreader" incubators across the world) to shut down, closed schools and restricted international flights. In general, though, South Korea’s social distancing measures have been relatively relaxed and short-lived compared to other hot spots in China, Europe and the United States.

The government has focused on finding ways to respond with a scalpel rather than a sledgehammer. Seoul's biggest success has been with mass testing, which it was able to quickly implement at scale because it had incentivized domestic biotech firms to start test development and production in January. When the Daegu outbreak began, hospitals already had diagnostic tests on hand, allowing them to confirm new cases and then test everyone new patients had come in contact with, irrespective of whether they were showing symptoms.

South Korea stood up more than 600 testing facilities within weeks, with enough tests to handle more than 20,000 people per day, and its universal health insurance scheme removed barriers for potential carriers to get tested early and often. This also allowed the country to conduct aggressive contact tracing, using smartphone apps and CCTV to effectively “tag” sick people, look back at where they might have spread the virus to others and warn the public to steer clear of areas where the virus may be lurking.

For the international community, the country’s success should provide a measure of optimism, even if it's too late for many countries to implement similar procedures — and even if such intrusive contact tracing tools will meet stiff political resistance in Western countries (their citizenry's blithe attitudes about handing data over to tech giants notwithstanding).

For South Korea — and for Moon’s administration in particular— the success ostensibly opens a window of opportunity to gain diplomatic favor, boost its core industries at the expense of competitors in countries like Japan, which is faring worse with the pandemic, and burnish its reputation as a well-governed, technologically advanced democracy capable of punching above its weight in the face of intractable global challenges.

Already, for example, it’s becoming a vital exporter of tests and equipment needed to combat the pandemic. And its success — like Taiwan’s — undercuts Chinese state media’s newfound narrative that, in a crisis, the Communist Party's tightly centralized model of governance is superior to that of liberal democracies.

The Limits of Success

But while South Korea is in a relatively good situation, the emphasis falls heavily on “relatively.” The coronavirus may have largely spared South Korean lives and lifestyles, but it took a bat to the South Korean economy anyway; the national gross domestic product is expected to contract this year by more than 1.5 percent.

The reality is that official lockdown measures aren’t the only thing suffocating economic activity across the globe. Fear of getting sick is itself a powerful motivator keeping people away from restaurants and stores — something that will bedevil efforts to “restart” economies by relaxing social distancing measures.

But the main problem for South Korea is the same that awaits exporting behemoths such as China, Japan and Germany as they return closer to full production capacity: the loss of foreign demand. Getting factories up and humming means little if there are no customers. Compared to its neighbors, the South’s strong fiscal position and high domestic consumption put it in pretty good shape to ride out the crisis without suffering structural damage to the economy.

Nonetheless, exports accounted for around 44 percent of South Korean GDP in 2019, and its domestic industry is grappling with widespread supply chain disruptions. Many South Koreans will be hurting until Europe and the United States recover, which might take years.

The popularity Moon gained for Seoul’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic may quickly evaporate once the economic toll truly begins to hit — particularly if Seoul is forced to lean more heavily on the large, family-owned conglomerates, known as chaebol, that dominate the South Korean economy and that he had pledged to reform during his run for office.

The looming recession will also force the Moon administration to redirect funding meant to make progress on thorny geopolitical issues, such as enticing North Korea out of its shell with lucrative financial enticements. And if China’s own recovery continues apace (though this is by no means a guarantee), then South Korea’s economic dependence on Chinese consumers will increase — something that Beijing has tried to weaponize in the past.

Seoul will also find it harder to fund research and development projects aimed at reducing dependence on Japanese imports of key tech sector supplies. Seoul’s relations with Pyongyang, Beijing and Tokyo were already highly politically contentious at home before the economic slump; Moon will likely find his stores of political capital very limited.

There’s also the lingering risk that the pandemic — whether the disease itself or the economic fallout — leads to major political destabilization in either China or North Korea. Somewhat paradoxically, neither would be particularly good news for Seoul. The more the Communist Party of China comes under political pressure at home, for example, the more likely it is to try to stir up nationalist forces to survive, including by becoming more aggressive abroad. South Korea isn’t typically the foremost target of nationalist ire in China, but it’s not wholly immune and, historically, it hasn’t fared well when caught in the crossfire between its more powerful neighbors.

Regarding North Korea, nobody knows how the COVID-19 crisis will shape Pyongyang’s behavior, in large part because nobody knows just how badly the virus has hit the country. Officially, the North has zero cases, which would be great if there weren’t also several reports from defectors and intelligence agencies that the outbreak there is actually widespread. North Korea’s weak health care system and isolation make it an epidemiological nightmare.

Meanwhile, the country is still conducting regular tests of an increasingly sophisticated arsenal of short-range weapons systems — the type intended to drive a wedge between South Korea and the United States and agitate for sanctions relief from the West. Denuclearization negotiations with the United States are still dead. And since last year, several hints have suggested that something is amiss in Pyongyang’s chambers of power.

A major power struggle or surge of public unrest would, at minimum, make it harder for Kim Jong Un’s regime to pursue the sort of risky diplomatic concessions needed to bring about a meaningful reconciliation with the South. Worse, such events could compel Pyongyang to try to rally domestic support by, say, shelling another South Korean island. Most alarming to Seoul, North Korean unrest would further strain the government’s already dodgy command-and-control problems over the military.

With Friends Like These

South Korea’s regional challenges would be more manageable if it was acting in tandem with its indispensable partner, the United States. But since 2017, Washington and Seoul have been increasingly at odds over a variety of issues, managing North Korea’s nuclear program chief among them.

More recently, the two sides have also been embroiled in contentious burden-sharing negotiations. The administration of U.S. President Donald Trump is demanding a fourfold increase in Seoul’s contributions to the costs of hosting U.S. troops; Seoul is reportedly offering a 13 percent increase.

Thousands of South Korean support staff at U.S. bases in the South were furloughed earlier this month as a result, and Seoul's mounting fiscal and political constraints will make it harder for it to budge anytime soon. The cost-sharing issue isn’t particularly important on its own; there’s little reason to think it will hinder the two militaries’ operational readiness.

But it reflects deeper issues in the alliance that, if left unresolved, have real potential to impact the regional geopolitical landscape.

Military alliances are never frictionless, particularly when one side’s forces are stationed on the other’s soil. In just about any alliance, the weaker partner typically frets about one of two things: either abandonment (as seen in the U.S.-Philippines and U.S.-Australian alliances) or entanglement in a fight not in its interest.

For an ally to fear both simultaneously is fairly rare, because in such cases the weaker ally is likely to feel extorted and look for a way out before the partnership turns into a politically unsustainable vassalage.

At present, South Korea fears both. It worries the United States will ignore its concerns and start a war with North Korea and/or China that would quite likely leave Seoul in ruins. It’s also worried that, as North Korea develops longer-range missiles and the capacity to put U.S. overseas bases at risk (if not the U.S. mainland itself), and as China’s anti-access and area denial buffer expands, the United States could reasonably conclude that South Korea isn’t worth shedding American blood over.

Implicit in the cost-sharing negotiations — and explicit in some of the Trump administration’s rhetoric — moreover, is that the United States is indeed willing to leave South Korea.

The U.S. positions aren’t without merit. Washington’s “fire and fury" approach to pressuring North Korea in 2017 didn’t force Pyongyang to capitulate, nor has its more recent maximum pressure campaign. But there’s an argument to be made that Pyongyang must be squeezed to the breaking point and realistically fear the threat of U.S. military action before it will make any movement toward denuclearization.

The United States, which is vulnerable to becoming militarily overstretched, also has a growing interest in discouraging allies (particularly prosperous ones with growing military budgets) from free-riding on U.S. security guarantees.

But to whatever extent Washington’s reasons are really valid, they only underscore the reality that U.S. and South Korean interests are diverging.

A U.S.-South Korean divorce is not imminent. The alliance is still broadly popular with the public and military planners on both sides. The United States benefits enormously from a forward position on China and North Korea’s doorstep. And it can (and probably will) back off its maximalist cost-sharing demands easily enough.

Moreover, South Korea doesn’t exactly have a plan B. But as the strategic moorings of an alliance weaken, its continued existence starts to hinge increasingly on inertia and assumption.

This makes it more vulnerable to a shock from which it might not recover — a well-timed move by an adversary to shatter the partnership, for example, or a pandemic that leaves domestic political landscapes or the regional power balance deeper in flux.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario