Stocks are slowly starting to price in the post-lockdown economic malaise. This could be a painful process for investors.

By Jon Sindreu

Back in March, the fastest bear market in history triggered widespread panic among investors.

This week’s wobbles are far less dramatic, but perhaps no less worrying.

The MSCI World index of developed countries’ stocks is on track to clock its worst weekly performance since the week through March 20, driven by mounting signs that lifting lockdowns won’t end the damage to the global economy.

European indexes are suffering more, in part because they lack big technology leaders like Amazon.comand Microsoftthat are reaping rewards from an increase in online shopping and working.

The “Fearless Girl” statue s shown with a surgical mask across from the New York Stock Exchange. / Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images .

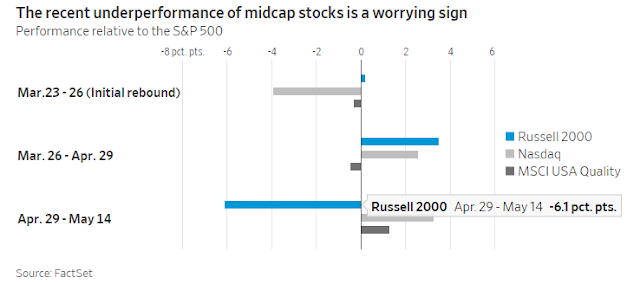

Yet even in the U.S. market confidence is fraying, particularly for smaller stocks that aren’t in the headline S&P 500. The Russell 2000 index of medium-size companies is down 7% this week.

On top of the risk of a second wave of Covid-19 infections that are now starting to materialize in Asia, last year’s geopolitical issues are back. These include U.S.-China tensions and the European Union’s post-Brexit negotiations with the U.K.

This puts even more emphasis on the question that investors have been asking themselves for almost two months now: How could it be rational that the stock market is doing so well when the economy gets weaker every day?

When the S&P 500 bottomed out on March 23, it had fallen 34% from its February peak in less than five weeks, driven in part by overconfident investors being forced to rush out of earlier bets.

This prompted odd market moves, such as safe-haven assets like the U.S. dollar and Treasurys initially selling off. By early April, though, the market had rebounded so strongly that it technically entered a bull market—defined as a 20% gain in the S&P 500.

Such rapid moves are very unusual. With the exception of the 1987 Black Monday crash, past bear markets didn’t start with steep selloffs, but a steady trickle of losses. This makes sense: Sudden moves aren’t usually driven by well-grounded decision making.

The deterioration in reliable economic and corporate data that ends up justifying bear markets often comes in successive doses.

Right now, despite high headline valuations, sentiment indicators suggest that stock pickers, and individual investors, in particular, aren’t exuberant. Because assessing the magnitude of a post-lockdown recession is simply impossible—unlike in 2008, this crisis is caused by factors outside the economy itself—markets have mostly just priced in the direct impact of shutdowns.

Where longer-term outcomes are easier to gauge, such as in aviation, the initial bounceback didn’t last. The Dow Jones U.S. Airlines Index is down 65% this year because travel demand is sure to be depressed for years, regardless of how the broader economy fares.

Investors have rightly overlooked the dismal economic data released in recent weeks, which contains little relevant information about the all-important post-lockdown period.

Now, though, the news is starting to become meaningful, and much of it isn’t good: Manufacturing giants Caterpillar and Polaris saying that they won’t reopen some furloughed factories is more concerning than any gross domestic product number.

At the moment, it is difficult for investors to know whether history offers a useful template for the future.

But a drip, drip, drip of bad news isn’t a good prospect for stocks.

0 comments:

Publicar un comentario